2016 Art & Race Series

January - October 2016

∞ mile in partnership with the University of Michigan Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design

2015 Art & Gentrification Series Conclusion + 2016 Art & Race Series Introduction

Managing Editors

stephen garrett dewyer, Ryan Harte and Jennifer Junkermeier

Visiting Editor and University of Michigan Stamps School of Art and Design Liaison

Rebekah Modrak

Visiting Editors

Wihad Al-Tawil

The 2016 Art & Race Series is part of an ongoing programming partnership between infinite mile and the University of Michigan Penny W. Stamps School of Art and Design. The first series, titled Art & Gentrification, launched in January 2015 as Detroit emerged from the largest Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy in United States history1. Since 1950, Detroit’s population has cumulatively declined by 1.1 million. Yet, in a historical shift, from 2010 to 2014, the population of Whites increased 14,290 (26%), Hispanic or Latino populations increased 3,433 (7%), while the Black population decreased by 49,307 (8.5%) according to the U.S. Census2. In concurrence with these population changes came concerns over who would benefit from new capital investments3. Meanwhile, water utility shutoffs and tax and mortgage foreclosures affected tens of thousands of poorer residents in the majority-African American city as corporations rebranded some neighborhoods to attract a wealthier and whiter demographic. While gentrification certainly plays out elsewhere in major cities across the U.S., there is perhaps no clearer indication of its racialization than in a city such as Detroit. Thus, infinite mile and the Penny W. Stamps School of Art and Design sought to organize a series to look critically at art and race.

The 2015 Art & Gentrification Series was not the first time the topic of gentrification in Detroit had been raised4, nor will it be the last5. Just one among many, the Art & Gentrification Series and panel discussion helped facilitate critical research, analysis and conversation about the role of gentrification through a local art and culture lens. The series looked critically at the relationship between art and gentrification at a time when art’s role in Detroit seems questionable as to whether or not it serves gentrification. While the history of art’s role in the gentrification of New York is well known, the art and cultural scenes in Detroit look somewhat different, although on the precipice of perhaps repeating the same narratives.

The Art & Gentrification Series looked further, finding that while art and artists may be precursors to gentrification, so are racial and economic disparities. In “Fast Gentrifying Neighborhoods, Slow Gentrifying Schools”, Syed Ali discusses the generic narrative for gentrification as, “[f]irst gays and artists move to an ‘edgy’ (read: ghetto) neighborhood, followed quickly by college students and young, not-so-rich professional ‘pioneers.’ The natives, Black usually, sometimes Latino or even White, but generally poor or working class, provide some background ethnic ambience for new arrivals”(infinite mile issue 17: May 2015). The protagonist Bill, in the Interboro Partners (project team: Tobias Armborst, Daniel D’Oca, Georgeen Theodore and Riley Gold) article “Bill and The Metal Mill in Loopholeville: Scenarios for Industrial Development in Greenpoint / Williamsburg”, is inspired that he might cash-in on the building he owns in Williamsburg when he sees a ‘1992 New York Magazine cover story titled “The New Bohemia: Over the Bridge to Williamsburg” because “[t]he picture on the cover featured a group of young, white, artist types seated at a French-looking cafe, sipping beer” (italics the organizers, infinite mile issue 17: May 2015). Rebekah Modrak lists the ingredients for gentrification:

Start with a neighborhood or city that lacks economic incentives or that is populated by minority groups, which are underserved by municipal services including education, transportation, street lighting, police response time and maintenance. Enter a mainly white, middle-class population. Investors clamor to underwrite new businesses, sponsor grants or to secure real estate” (Modrak. “Bougie Crap: Art, Design and Gentrification”. infinite mile. issue 14: February 2015).

This, along with the increase of race-related police brutality throughout U.S. cities, along with an increasing loss of basic civil and human rights6 for many, sets the stage for what seems like a logical next step for infinite mile’s next series. Meanwhile, student protests at universities across the United States caused some universities to rename schools7 and dismantle monuments8 that partly commemorated the country’s racist history. Hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants face unjust immigration systems. With the current issues brought to the foray, art and race seemed the most relevant and critical topic for series number two.

1. Class and Race Divisions in Art

What do the above issues have to do with art? As capital appears on the move to an increasingly globalized (not planetary9) world, art appears to shift from a Western, White canon to an increasingly racially diverse set of actors. But with the globalized art world also come race and class inequities exacerbated by global capital. Examples of the shift include the hundreds of art biennials that appear in cities across the world including Istanbul, Gwangju, São Paulo, Sharjah, Havana, Dak’art, Shanghai, Marrakech and Taipei, with major shifts largely appearing in post-colonial nations. From 2002 - 2013, the Chinese State Administration of Cultural Heritage built nearly 1,500 new museums in a move meant to emulate the ambitions of China’s Great Leap Forward (1958 - 1961)10. In 2006, the City of Abu Dhabi announced an agreement with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation to build a Guggenheim Museum on Saadiyat Island11, a cultural district where, a year later, plans to build the Louvre Abu Dhabi were announced. The expansions of art institutions globally have often received demonstrations around issues of neocolonialism and labor rights, exposing deep inequities between the producers, consumers and financiers of art.

At the same time art receives increasingly globalized attention, the role of race in art appears very homogeneous on a local level. In the United States, nearly 80%12 of the museum workforce and 78.9%13 of museum visitors are White according to two studies published in 2009 and 2010 by the American Association of Museums14. In the City of Detroit, the majority of art organizations are White owned and/or operated while the City of Detroit is majority African-American15. The audiences of the art organizations also largely reflect the racial composition of the owners and/or operators with a few critical exceptions. Why the de facto racial segregation in art? Placing blame strictly on art organizations ignores the role audiences play in supporting art and how they happen. Here, education plays a role. The large absence of art education from K-1216, college and university educations17 except for wealthier and often Whiter programs diminishes the audiences art can reach. Without adequate education in art, understandings of the role of art in society suffers. Yet, art organizations can help by making art increasingly relevant to audiences across races.

2. Cultural Appropriation

While not new to art, the issue of cultural appropriation becomes fraught with racial biases meant to serve a particular race and class while appearing to lend that race and class credibility with a “native” constituency it seeks to exploit. Visiting editor and Stamps Liaison Rebekah Modrak invokes the term “swagger-jacking,” explaining that:

swagger-jacking happens where brands such as Shinola drape themselves in black cultural signifiers and claim to be “of the city”, trolling for street credibility. While representing themselves with images of black, pig-tailed girls, poets and rappers, their point of authority is still Europe, executive and creative leadership. Their consumer base is still [W]hite, and the assembly line and workforce is primarily [B]lack. Swagger-jacking is the code of the twenty-first century colonizer.

Swagger-jacking is taught as a capitalist strategy at the University of Michigan campus. In a lecture given by Shinola’s president Jacques Panis at the College of Engineering Center for Entrepreneurship on 13 March 2015, Panis started his lecture with a projection of a [B]lack child. With “Shinola” imprinted on her chest, he told students:Think about Detroit. Think about the opportunity that’s there, and I think Shinola speaks to that and is something for you guys and gals as you all venture out into the Wild West. Is Detroit an opportunity for you? …. You know, starting up a watch factory in Detroit, just to give you a sense, did not take two guys sitting on the opposite sides of a big boardroom table, it took one, wild, drunk Indian to do this.Here, Panis intentionally disregards Shinola’s actual business strategies and, as common in their promotional videos, instead, boasts of their enterprise as “crazy.” Selling expensive watches to people with disposable income is hardly crazy. By embedding themselves in Detroit and exposing their suburban clientele to the authentic, cultural expression of the natives, companies like Shinola assume an alleged edginess for their luxury products. Swagger-jacking is about race, culture and power, which makes it insidious and destructive and all the reason why we, as artists and cultural critics, must expose and not perpetuate or benefit by it.

Although not the only example of cultural appropriation, swagger-jacking is specific to the aesthetics of Detroit. The series hopes to look critically at the various forms of cultural appropriation.

3. Re-Imagining Race

In organizing the Art & Race Series, the editors questioned the meaning of race; and each editor’s definition differred based on his or her experience of race. For Visiting Editor Wihad Al-Tawil, “race is an ubiquitous expression of existence through nonexistence.” She goes on to explain:

[o]f particular importance to me is the study of race relations in America since they tend to define so profoundly our cultural history and current socio-political framework. Race, with no genetic evidence to prove it as scientifically founded, has historically enabled groups to exert superiority and control over neighboring groups of otherwise identical circumstances and potential…. As an Arab-American in Detroit, a myriad of experiences with regard to race, culture, and identity have instilled in me a unique perspective. I have grown critically cognizant of public representations of race especially in the media. As an art historian, I am fascinated by the ability of those in power to produce self-motivated narratives through art and imagery18. Historically speaking, this has always been the case—as is the profound psychological effects on constituencies.

For others, race is a given in every aspect of life and constituted by the biopolitical19. At some points, the lines between races blurs, causing the image of race to appear anything but permanent. This series seeks to show the changing faces of race.

The history of Detroit is infused with a variety of races and ethnicities moving to and from the city for different reasons. African American, Albanian, Bangladeshi, Belgian, Bulgarian-Macedonian, Chaldean, Chinese, Filipino, Greek, Hmong, Hungarian, Indian, Iraqi, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Lao, Lebanese, Maltese, Mexican, Pakistani, Polish, Romanian, South Asian, Syrian and Vietnamese comprise some of the demographics in Detroit20. To cast Detroit as Black and White ignores the transnational situation of the city. The transnational, here, is the movement of different forms of sovereignty across national boundaries. Race is but one type of transnational identity. Our series will not limit its scope of discussion or engagement to one or two races but recognize that we are living in a community, in a city, a state, nation and world of many races.

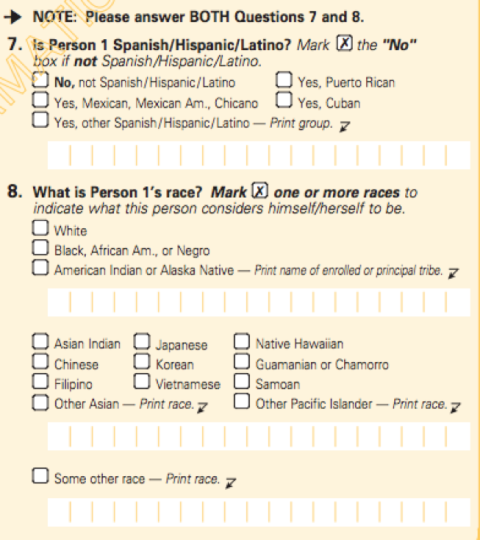

For some, race is an amalgamation of different races21. Such amalgamations become apparent in the historical shifts of the U.S. Census Bureau although, today, the census remains limited to six broad categories for race22. Choosing a box that defines one’s race can be a struggle to fit in, a reminder of inequality, or also a source of pride. Not until the 2000 Census could respondents select more than one race. Views of race as demonstrated by the evolving classifications by the Census and other regulatory initiatives (one-drop rules, redlining, slum-clearing urban renewal), reveals longstanding fears of racial intermingling in opposition to the virtuous rhetoric pronouncing a multicultural idealism that the United States is “a melting pot” or “a nation of immigrants.”

It is critical to note although Detroit is home to one of the largest Arab American communities in the United States23, the U.S. Census has no category for Arab-Americans, who are multiethnic and multi-racial. Thus, racial identity has complications and cultural connotations that do not always align with one’s own self-identification, public self-expression or another’s categorization. Our perceptions have been formed, and it is our responsibility to address critically the reasons why.

More than answers, this series seeks to give nuance through a diversity of perspectives and understandings to the conversation with art and race continuing to change.

If we seek a more just worldview of art and race, then we must re-imagine our perceptions of how art and race fit into both the historic and changing tides of inequality. In Detroit, the opportunity and challenge comes from remembering the city’s complex racial history even while reconstructing atop a shell of one. Visiting Editor Aaron Foley writes: “The opportunity and challenge here for infinite mile is to be a beacon of inclusiveness. The intersection of art and race is where we can learn from Detroit’s past and apply those lessons to our future, but also make sure that Detroit’s canvas is just as colorful as it should be.” As the Art & Gentrification series aimed to raise awareness of how art and artists may impact or influence gentrification, the art and race series, inturn, aims to raise awareness on how art and artists impact notions of race and identity.

4. Series Articles

A Series on Art + Race

∞ mile and the University of Michigan Penny W. Stamps School of Art and Design have partnered to publish a series of articles about art and race that will appear in the January - September issues of ∞ mile. The series invites a diverse group of contributors from multiple disciplines and locations to write on the subject, with specific attention paid to the role of art. The series organizers provided topic prompts and questions to invited writers but gave the writers autonomy to write on what they felt relevant. The articles could discuss art and race within and beyond Detroit.

Footnotes

1 In December 2014.

2 Aguilar, Louis and Christine MacDonald. “Detroit’s white population up after decades of decline”. The Detroit News. 17 September 2015.

3 I.e. private foundation grants; corporate relocations to Detroit; non-profit corporations such as Midtown Detroit Inc. and Downtown Detroit Partnership; for-profit financial institutions such as Quicken Loans, Rock Ventures and J. P. Morgan Chase; real-estate companies such as Olympia Development; and millions of U.S. Federal dollars for blight removal (Detroit received $50 million in December 2014, $21.2 million in October 2015 and $3.7 million in November 2015 from the U.S. Departmen of the Treasury's Hardest Hit Fund).

4 See Model D’s panel discussion at Carr Center in December 2011.

5 See "Gentrification Leaves Black Residents Behind" by Kimberly Hayes Taylor, 1 November 2015.

6 E.g. the killing of unarmed African Americans such as Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice and Freddie Gray and the start of the Black Lives Matter movement.

7 Brait. “Princeton students demand removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name from buildings”. The Guardian. 23 November 2015.

8 Rosen. “University of Texas at Austin Moves Confederate Statue”. The New York Times. 30 August 2015.

9 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak writes: “[g]lobalization is achieved by the imposition of the same system of exchange everywhere. It is not too fanciful to say that, in the gridwork of electronic capital, we achieve something that resembles that abstract ball covered in latitudes and longitudes, cut by virtual lines--once the equator and the tropics, now drawn increasingly by other requirements--imperatives?--of Geographical Information Systems. The globe is on our computers. No one lives there; and we think that we can aim to control globality. The planet is in the species of alterity, belonging to another system; and yet we inhabit it on loan. It is not really amenable to a neat contrast with the globe. I cannot say “on the other hand.” (Spivak. “Imperative to Re-imagine the Planet” from An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. 2012: p. 338).

10 “During the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s, the Chinese Communist Party had a slogan: “Every county must have its museum, every commune its exhibition hall.” In 2002, the Chinese government rededicated itself to that ideal, when the State Administration of Cultural Heritage announced that the country would build one thousand museums by 2015. As improbably ambitious as that pronouncement might seem, it was in fact accomplished far ahead of schedule. By 2013, the country had already built almost fifteen hundred museums… And the building has continued apace… The CCP inherited just twenty-five public museums when it founded the People’s Republic in 1949.” (Wong. “Arresting Development: Winne Wong on China’s museum boom”. Artforum. November 2015 [Volume 54: No. 3]: p. 123).

11 Numerous Occupy Wall Street protests occupied the Guggenheim calling for better treatment of workers, rights to organize, a fund to settle all recruitment debts and a living wage (Sutton. “May Day Occupation at Guggenheim Closes Museum #GuggOccupied”. Hyperallergic. 1 May 2015). See also Batty and Carrick’s "In Abu Dhabi, they call it Happiness Island. But for the migrant workers, it is a place of misery" (The Guardian on 21 December 2015).

12 American Association of Museums. “The Museum Workforce in the United States (2009): A Data Snapshot from the American Association of Museums”. November 2011.

13 American Association of Museums. “Demographic Transformation and the Future of Museums”. 2010.

14 Now American Alliance of Museums.

15 Khan. “Set Strait”. infinite mile. issue 01: December 2013.

16 For example, in Lansing, Michigan: “district officials say cutting [art teachers ie art specialists] specialists was tough but necessary. The district’s enrollment is dwindling. State funding is down. And a lot of Lansing kids come from low-income families, making it tough to get big donations from the parent community....National arts groups use Lansing as example of what not to do. There are, however, plenty of educators and arts advocates who strenuously argue that these cuts are directly hurting the kids” (Wells. “After cutting arts teachers, schools adjust to new normal in Lansing”. Michigan Radio.org. 27 January 2014. Accessed 4 January 2016).

17 A roundtable with Helen Molesworth, Mike Essl, Jory Rabinovitz, Lee Relvas, Amanda Ross-Ho, Victoria Sobel, Frances Stark, A. L. Steiner and Charlie White with an introduction by Sarah Lehrer-Grawer discusses the cultural and economic divide between university administrators, students and faculty in “Class Dismissed: a Roundtable on Art School, USC, and Cooper Union” (Artforum, October 2015).

18 Al-Tawil. “Narrative Construction, Race and the Authentic Detroit”. infinite mile. Issue 14: February 2015.

19 In an interview with Jacques Rancière by Eric Alliez in March 2000, Rancière discusses the differences between biopolitics, a term he theorizes as synonymous with policing, and politics, a term he theorizes as the paradoxical relation between two different distributions of the sensible. Rancière writes: “[i]n Foucault’s ‘biopolitics’, the body in question is the body as object of power and, therefore, it is localized in the police distribution of bodies and their aggregations… It does not help to say that he used the terms biopolitics and biopower interchangeably, the point is that his conception of politics is constructed around the question of power, that he was never drawn theoretically to the question of political subjectivation” (Rancière. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. 2010: p. 93).

20 “Ethnic groups in Metro-Detroit”. Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnic_groups_in_Metro_Detroit. Accessed 9 January 2016.

21 Professional golfer Tiger Woods once said he is not just an African American, but, instead “Cabinasian”, “a portmanteau Caucasian, black, Indian and Asian”, on the Oprah Winfrey Show

("Woods stars on Oprah, says he's 'Cablinasian'". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Associated Press. April 23, 1997).

22 As an official measure of race in the United States, the Census’ classification of race has evolved quite significantly from the first census in 1790, which asked the number of White males, White females, other free persons, and slaves in the household. In 1850, the selection of color was designated as White, Black or Mulatto. After the Civil War, the 1870 census included White, Black, Mulatto, Chinese (which represented all East Asians) and Indian (Native American). Previously, Native Americans were potentially counted as other free persons, Mulatto, sometimes written in as “Ind.” The Census did not count “Indians not taxed” who were living on reservations or on frontier lands, “wild.” “Indians and the Census 1790 - 2010” Native Heritage Project. 14 May 2013. Accessed 9 January 2016. http://nativeheritageproject.com/2013/05/14/indians-and-the-census-1790-2010/

23 Wihad Al-Tawil writes:

Identity through art is no stranger to my personal experience as an Arab American. In the 1970s, my parents were involved in an artistic revolution in Baghdad, driven in part by the yearning for identity through the Mesopotamian cultural tradition of progress. After the first Gulf War, many Iraqis (and other Arabs) like my parents were displaced, either seeking refuge in America or stripped of the option to return to their homelands. This wave of Arabs to Detroit in the 1990s produced a community of displaced artists who, decades prior, revolutionized artistic expression during a cultural renaissance in Baghdad, and now, were grieving the potential loss of identity and the destruction of the world they had fought so hard to preserve. My father and many like him mourned Baghdad through art. Imagined landscapes mixed with purely Arab cultural cues filled every canvas. As a result, I understood art as the unequivocal reflection of self—and in turn, identity. For additional information read Sarah Cwiek’s “What explains Michigan’s large Arab-American community?” (Michigan Public Radio. 9 July 2014).

24 Sample Census Form D-61A. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/dmd/www/pdf/d61a.pdf

Works Cited

Aguilar, Louis and Christine MacDonald. “Detroit’s white population up after decades of decline”. The Detroit News. 17 September 2015. http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/detroit-city/

2015/09/17/detroit-white-population-rises-census-shows/72371118/

Al-Tawil. “Narrative Construction, Race and the Authentic Detroit”. infinite mile. Issue 14: February 2015. http://infinitemiledetroit.com/

Narrative_Construction,_Race_and_the_Authentic_Detroit.html

Ali, Syed. “Fast Gentrifying Neighborhoods, Slow Gentrifying Schools”. infinite mile. Issue 17: May 2015. http://infinitemiledetroit.com/Fast_gentrifying_

neighborhoods,_slow_gentrifying_schools.html

American Association of Museums. “Demographic Transformation and the Future of Museums”. 2010. Accessed 1 January 2016. http://www.aam-us.org/docs/center-for-the-future-of-museums/demotransaam2010.pdf

Arts Education Partnership. “State of the States 2015 Arts Education Policy Summary”. March 2015. http://www.aep-arts.org/wp-content/uploads/State-of-the-States-2015.pdf

Batty, David and Glenn Carrick. "In Abu Dhabi, they call it Happiness Island. But for the migrant workers, it is a place of misery". The Guardian. 1 December 2015. Accessed 1 January 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/22/abu-dhabi-happiness-island-misery

Brait, Ellen. “Princeton students demand removal of Woodrow Wilson’s name from buildings”. The Guardian. 23 November 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/education/2015/nov/23/princeton-woodrow-wilson-racism-students-remove-name

Cwiek, Sarah. “What explains Michigan’s large Arab-American community?” Michigan Public Radio. 9 July 2014. Accessed 1 January 2016. http://michiganradio.org/post/what-explains-michigans-large-arab-american-community#stream/0

Essle, Mike, Helen Molesworth, Jory Rabinovitz, Lee Relvas, Amanda Ross-Ho, Victoria Sobel, Frances Stark, A. L. Steiner and Charlie White (roundtable) with an introduction by Sarah Lehrer-Grawer. “Class Dismissed: a Roundtable on Art School, USC, and Cooper Union”. Artforum. October 2015. https://artforum.com/inprint/issue=201508&id=54967

Interboro Partners (project team: Tobias Armborst, Daniel D’Oca, Georgeen Theodore and Riley Gold) “Bill and The Metal Mill in Loopholeville: Scenarios for Industrial Development in Greenpoint / Williamsburg”. infinite mile. Issue 17: May 2015. http://infinitemiledetroit.com/Bill_and_The_Metal_Mill_in_Loopholeville,

_Scenarios_for_Industrial_Development_in_Greenpoint_-_Williamsburg.html

Jacques, Panis. Lecture to the University of Michigan College of Engineering Center for Entrepreneurship. 13 March 2015.

Jestes, Roberta. “Indians and the Census 1790-2010”. Native Heritage Project. 14 May 2013. Accessed 1 January 2016. http://nativeheritageproject.com/2013/05/

14/indians-and-the-census-1790-2010/

Khan, Osman. “Set Strait”. infinite mile. Issue 01: December 2013. http://www.infinitemiledetroit.com/Set_Strait.html

Modrak, Rebekah. “Bougie Crap: Art, Design and Gentrification”. infinite mile. Issue 14: February 2015. http://infinitemiledetroit.com/Bougie_Crap_

Art,_Design_and_Gentrification.html

Panel discussion on 14 December 2011 at the Carr Cultural Arts Center featuring speakers Kurt Metzger, Noah Stephens, Megan Elliott, Burney Johnson, Malik Goodwin, Larry Mongo, Lori Robinson and Lottie Spady and moderated by Jeff Wattrick. “Model D Speaker Series: Gentrification”. Model D. 29 November 2011. http://www.modeldmedia.com/features/gentrification1111.aspx

Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Edited and Translated by Steven Corcoran. Continuum: London and New York. 2010: p. 93

Rosen, Kenneth. “University of Texas at Austin Moves Confederate Statue”. The New York Times. 30 August 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/31/us/texas-university-moves-confederate-statue.html

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. “Imperative to Re-imagine the Planet” from An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA and London, England. 2012: p. 338.

Sutton, Benjamin,. “May Day Occupation at Guggenheim Closes Museum #GuggOccupied”. Hyperallergic. 1 May 2015. Accessed 1 January 2016. http://hyperallergic.com/203794/breaking-may

-day-occupation-at-guggenheim-closes-museum-guggoccupied/

Taylor, Kimberly Hayes. “Gentrification of Detroit Leaves Black-Owned Businesses Behind”. NBC News. 1 November 2015. Accessed 1 January 2016. http://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/gentrification-detroit-leaves-black-residents-behind-n412476

Wells, Kate. “After cutting arts teachers, schools adjust to new normal in Lansing”. Michigan Radio.org. 27 January 2014. Accessed 1/4/2016. http://michiganradio.org/post/after-cutting-arts-teachers-schools-adjust-new-normal-lansing#stream/0

Wong, Winnie. “Arresting Development: Winne Wong on China’s museum boom”. Artforum. November 2015 (Volume 54: No. 3): p. 123.

"Woods stars on Oprah, says he's 'Cablinasian'". Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Associated Press. 23 April 1997. http://web.archive.org/web/20071212010355/

http://www.lubbockonline.com/news/042397/woods.htm