Detroit is a complex city with an even more complex history. The specific details of the economic rise, fall, deindustrialization, and ultimate collapse of the city have been well documented and discussed extensively for decades. The need for an economic stimulus has been established as a primary factor in truly revitalizing all of Detroit. Other ideas, like that of business mogul Dan Gilbert, foresee loopholes in revitalizing the city, provided in part by extensive bank account access. The exciting proposals talk of an influx of storefronts, transit systems and, most importantly, people. In fact, Detroit is facing a pivotal time where these changes have become apparent in main hubs such as Downtown, Midtown, and Corktown. Still, critics of capitalists like Gilbert find fault in their naiveté or otherwise deliberate ignoring of the rest of the 137 square miles of residential land that about 700,000 Detroit citizens occupy. Whether Gilbert or any other individual’s plan achieves any success, one glaring aspect cannot be ignored, and that is the touchy matter of race relations. As of today, about 83 percent of the City of Detroit residents are African-American, while the population of Metro Detroit (including the City of Detroit and its surrounding area) is 70 percent White, 22.8 percent African-American, 6.2 percent Hispanic or Latino of any race and 3.3 percent Asian according to the 2010 U.S. Census. The numbers tell of an astronomically high number that demarcates a definite level of segregation in the city. On any given afternoon, a spectator of the city can walk downtown and notice the obvious implications of gentrification taking place towards the city center. The outliers seem inconsequential, or expected to find a way to thrive once the city thrives; perhaps a modern day application of survival of the fittest. But with no workable industry to draw an influx of job opportunities and a stable economy, it doesn’t seem completely probable that the city will integrate following a downtown revitalization. A question arises quite quickly: why is perhaps the most economically unstable city in the United States overwhelmingly inhabited by African-Americans? Of course, certain socio-economic circumstances play a role in any segregated and unbalanced society, but often times the simple fact of racism is overlooked.

Racism is an operative factor in why Detroit is a crumbled city, and why it has been abandoned and intentionally forgotten. Detroit imagery has depicted the effects of racism since the turn of the century and, more specifically, immediately after World War II, through the Riots of ‘67 and to the present day. Images of black men against backdrops of abandoned, burnt-out storefronts commonly appear in contemporary newspapers and cover stories. Such images, whether a person consciously makes the connection or not, work to perpetuate a “black and scary” image of Detroit. Beginning in the late 1940s, different media images have perpetuated a social stigma about Detroit, one that links African-Americans with the deterioration of the city, perpetuates stereotypes about the city and its people and reinforces racist ideologies which, in turn, keep the city segregated and poor.

The imagery of African-Americans in Detroit effectively reinforced negative ideas about the city. Certain media imagery has crafted a narrative featuring racist undertones that link white people to the Golden Age of Detroit and black people with its failure. In this presentation, I will focus on media images from the albums of two major news outlets: Time & LIFE, and the Detroit News.

Michael Borshuk describes a constructed narrative linking African-Americans with a desolate backdrop in his essay, “True Tales And 8 Mile Memoirs: Exploring The Imaginary City Of Detroit”. In the essay, Borshuk lists Detroit as a “mirror” image of the ideal American metropolis—one where attractively dressed white people fill a skyscrapered urban space. The mirror, then, is the opposite occurrence—black instead of white, abandoned and destroyed in place of pristine or majestic (Borshuk, 111). This idea of the “decay into blackness” has become the prominent narrative of Detroit, whether imagined or not. The deterioration-- both in population loss and crumbling infrastructure --happens to correlate directly with the vanished white population and majority black population.

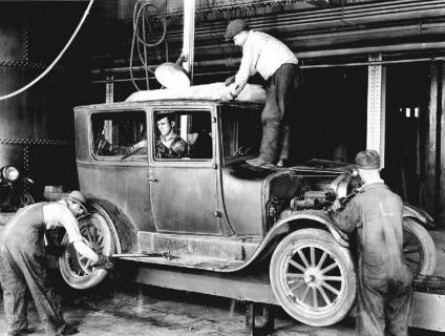

A collection of photographs owned by the Detroit News entitled “Vintage Detroit” support the narrative of white flight. The album features copyrighted, untitled photography intended for media use. The title “Vintage Detroit” bears implications of an ideal Detroit city. The subject matter features young, white men and women dressed in their Sunday best, thriving within the hustle and bustle of the Motor City (fig. 1). “Vintage Detroit,” then, implies that the authentic Detroit was a white Detroit. Of course, African-Americans began migrating to Detroit in the decades prior to the photos, which were taken in the 1930s, to work for the Ford plants. According to Thomas Sugrue in his essay “Race and Inequality in Post War Detroit”, at least 80 percent of non-White men between the ages of 20 and 29 were employed by the labor force in Detroit by 1960, implying that minorities, presumably African-Americans, were a present population at the time that the photos were taken. Furthermore, Sugrue indicates that this percentage had actually been on the decline by 1960, and the decades preceding actually had more non-White workers in the auto- plants. Still, they are left out of the narratives of the history of Detroit. Figure 2 illustrates this reality: a photo featuring white workers inside the Ford River Rouge plant in 1930. In fact, the Detroit News’ entire “Ford” collection of “Vintage Detroit” photos fail to include a single African-American worker. Even during such a significant moment as the unveiling of the final bomber at Willow Run during World War II, no African-American men can be spotted in the photo (fig.3). Keeping such a present population deliberately out of the press photos are a direct reflection of how Detroiters viewed Detroit at the time—bright, and white.

The Detroit News “Vintage Detroit” collection reveals a certain idealism; heavily romanticized buildings draped with the lush leaves of the foliage such as those on Pietty Hill (fig. 4). Another where tightly corseted women walk poised next to Model T’s is reminiscent of early impressionist painting (fig. 5). African-Americans make appearances in the collection in a photo taken during the 1943 riots. A black man is included as an offender and not as a citizen; instead he is surrounded by state troopers with their guns drawn (fig.6). The photo as a response to the riots is a statement of control. He is unarmed, and it seems quite superfluous at least ten armed men would be required to hold him back (fig. 6). The race riots, as they have been deemed, happened at a time when African-American men were demanding more jobs in the auto plants. According to Thomas Sugrue, automation and new technologies were decreasing the amount of low-skill, entry-level jobs that most black men would have been offered. In fact, Sugrue states that by the early 1960s, these jobs had been eliminated altogether, forming a new permanently jobless class of black men (Sugrue, 144). Those who had moved to Detroit from the South in search of jobs and new opportunities were now facing an ugly reality: decentralization and automation meant there were virtually no jobs left for black men in Detroit. Together with no income to thrive off of, no work to start anew and no suburb to move to due to racist housing clauses, African-American families were essentially trapped in the city with nowhere to go (Sugrue, 148-9).

Detroit was the place to be in celebration of American victory during World War II (fig. 7). Absent in the photos are the hardships of the lower class—instead, portrayed are hardworking white Detroiters supporting the war effort through industry. White men and women alike are shown uniformed and happy against industrial settings (fig. 8). The Detroit News collection of World War II photos shows no trace of the black worker-- in this way, photos of hardworking black Americans have been left out of Detroit history. Instead, blacks are shown as defiant and non-law abiding in images related to the 1943 race riots, effectively categorizing their presence in Detroit as a shame, and furthering an image of Detroit where blacks were not welcome.

The 1967 Riots produced an alarming number of photos where African-American men are shown in aggressive and hostile scenes in downtown Detroit. The photos by Lee Balterman in the Time & Life Picture collection are titled “Detroit Burning: Photos from the 1967 Riot”—a title that demarcates a turning point in Detroit’s history. Mark Binelli, author of “Detroit City is the Place to Be” (Metropolis, 2012), further elaborates this point, stating:

Often, people incorrectly isolate the 1967 riot as the pivotal Detroit gone-wrong moment, after which nothing ever went right. In fact, the auto industry had been in a serious economic slump for at least a decade prior, with tension in the black community festering for even longer and the axial shift of jobs and white residents from city proper to suburbs solidly under way (Binelli, 3).

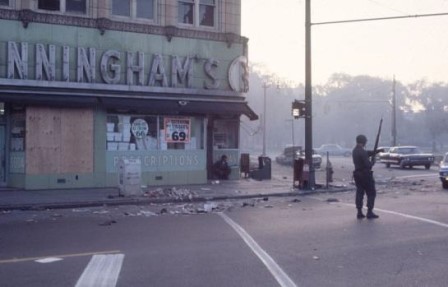

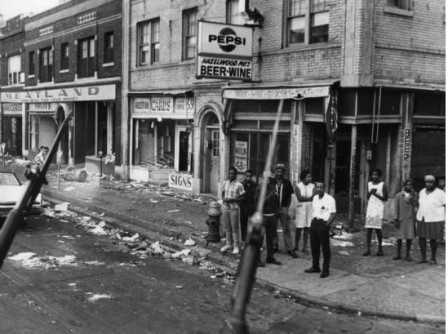

The Detroit narrative, however, leaves these important facts out, and instead focuses on the destruction caused by the riots, juxtaposed with urban black men and women, essentially making a statement on who is to blame for the chaos. In the first photo by Lee Balterman, a group of black men and women are surrounded by armed white paratroopers (fig. 9). Figures 10 through 12 display images which bring to life the destruction caused to the urban landscape of 12th Street, where the riots were centered. Each of these photos clearly displays at least one white, armed paratrooper stationed in response to the riots. Finally, Figure 13, a photo of African-American families lined-up against a building wall is captioned in the album: Police evacuate an apartment building in search of sniper suspects during riot. The photo clearly draws a link between the riots and the African-American residents of the City of Detroit.

A photo from the Detroit News’ “1967 Riots” collection (fig. 14) also reflects the racism within the Detroit narrative. African-American residents of Detroit, standing in front of a burnt, destroyed shell of a building, all while being confronted by the loaded rifles of government-appointed troops sent to contain the crowds. The implications of this photo are apparent: the residents of the city were responsible for the destruction, and the residents of the city were all black. This moment in time is what Binelli refers to as “Detroit gone-wrong”; even if it is a historically inaccurate statement, one where prior to 1967, African-Americans were either invisible or unwelcome, and after, became the people to blame for the marred city.

The archives of such prominent media outlets as the Detroit News and Time & Life reveal a nostalgia associated with the Golden Age of Detroit as white and upper-class, erasing all traces of African-Americans living and working in the city. Later, the archives instead incorporate their presence in photos related to hostility, violence, and urban deterioration. The media archives reflect the mentality of a racist world which existed and was clearly expressed through the careful manipulation of media imagery over the past century. The implications of these photos assert that as long as the city is inhabited by African-Americans, it is incongruous with the Renaissance City, and effectively perpetuates racist ideologies linking blacks to the urban decay that is currently visible. The Detroit narrative, then, refers to the notion of an authentic Detroit, one that existed pre-black riots but post-black worker. On one hand, the black worker is left out of the narrative, while on the other hand, the black rioter is included only to demarcate the fact that blacks were present when the riots took place. This in turn causes a direct association between the “fall of Detroit” and the African-American resident, as is clearly illustrated to us by the photos belonging to the Detroit News and Time & Life Pictures. The photos from both collections are the biased foundation of a commonly accepted but inaccurate narrative. The received tale of Detroit, as we can see, existed in the minds, writing and photo-documentation of the people who thrived at the time. Furthermore, this narrative continues to operate in the media’s negative portrayal of young black urban men in Detroit and beyond.

Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New

York: New, 2010. Print.

Binelli, Mark. Introduction. Detroit City Is The Place to Be: The Afterlife of an American Metropolis. New York: Metropolitan, 2012. 1-17. Print.

Borshuk, Michael. "True tales and 8 Mile Memoirs: Exploring the Imaginary City of

Detroit". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 41, no. 1: Scopus®, EBSCOhost. 2008

Sugrue, Thomas J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1996. Print.

| figure 1 |

|

| Untitled, Undated. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., n.d. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 2 |

|

| Untitled, June 1930. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., 1930.Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 3 |

|

| Untitled, 1945. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., 1945. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 4 |

|

| Untitled, Undated. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., n.d. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 5 |

|

| Untitled, Undated. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., n.d. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 6 |

|

| Untitled, June 1943. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., 1943. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 7 |

|

| Untitled, Undated. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., n.d. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 8 |

|

| Untitled, 1943. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., 1943. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 9 |

|

| Balterman, Lee. Untitled, 1967. Digital image. Time & Life Pictures. Getty Images, 1967. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 10 |

|

Balterman, Lee. Untitled, 1967. Digital image. Time & Life Pictures. Getty Images,

1967. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 11 |

|

Balterman, Lee. Untitled, 1967. Digital image. Time & Life Pictures. Getty Images,

1967. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 12 |

|

Balterman, Lee. Untitled, 1967. Digital image. Time & Life Pictures. Getty Images,

1967. Web. March - April 2013. |

| |

| figure 13 |

|

Balterman, Lee. Untitled, 1967. Digital image. Time & Life Pictures. Getty Images,

1967. Web. March - April 2013 |

| |

| figure 14 |

|

| Untitled, 1967. Digital image. The Detroit News. N.p., 1967. Web. March - April 2013 |

|