figure 1

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

On 15 February 2014, infinite mile prematurely ended its issue #3 release party and caravaned to the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD) to attend Dick's Last Stand (DLS) (fig. 1), a performance by artist Donelle Woolford. In Dick's Last Stand, a Woolford dressed in drag plays Richard Pryor playing one of his alter egos, Mudbone in a re-enactment of the fourth and last episode of “The Richard Pryor Show” (1977). The episode NBC never aired and was performed in front of a live audience.

Donelle Woolford is a young African-American woman born in Detroit, MI. She earned a B.A. in Fine Art from Yale University and has shown internationally over the past 10 years. Woolford is represented by Wallspace, New York and Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna.

In a tease, Donelle Woolford is a fictitious character created by the artist Joe Scanlan. Five actors (all of whom are African-American women) play and develop their own take on Woolford and ‘collaborate’ with Scanlan on her work, persona and trajectory.

Dick’s Last Stand tours various venues across the United States as part of the 2014 Whitney Biennial. DLS started touring on 31 January 2014 at the L.A. Art Book Fair, Los Angeles, and is scheduled to conclude 24 May 2014 at the Contemporary Art Center, Peoria, Illinois. In conjunction with the touring performances, paintings by Donelle Woolford (fig. 2) are on-view in the 2014 Whitney Biennial on the fourth floor of the Whitney Museum of American Art (7 March - 25 May 2014).

figure 2

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Detumescence, 2013

ink, paper, glue, and gesso on linen

|

Intrigued by Woolford, the performance at MOCAD and its part in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, a text investigating all in infinite mile seemed critical. The work provides numerous layers that burst at their seams with issues and problems set to unpack. In part, the unexpected divergences DLS takes from the consensus on “identity” art provided the interest in analyzing its turns.

While continually looking for ways to further engage our audience within and beyond Detroit, the art community and our readers/viewers, a roundtable discussion made sense. Participants in the art community in Detroit (whom attended the performance), Joe Scanlan and “Donelle Woolford” were invited to take part in the discussion.1 The roundtable happened via email, over dinner and editing sessions represented in the following text.

figure 3

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

Email #1

From: Jennifer Junkermeier

To: Group

Everyone included on this email has expressed interest in being part of the Dick's Last Stand round-table discussion article for infinite mile. Your level of involvement is up to you but you've been invited because we value your thoughts and want to encourage you to speak/write freely on the topics presented.

We'd like to begin the roundtable discussion "article" with a basic deconstruction of Donelle Woolford. Ultimately, I think that our discussion should focus on the DLS performance, but believe that discussing Donelle’s creation, development, and varying manifestations might be helpful for us to get started. Questions for us to consider: What is the artwork? How do you feel about using 'other people' as a 'medium' for an artwork? How do you define the fictional character, Donelle Woolford? Why? What does it mean and how do you feel that the artist Joe Scanlan created a fictional artist with a completely different background and identity than himself to be the stand-in "author" of a work he is creating? How do we understand the artwork that Donelle Woolford is creating if we know she is a fiction? Is it important for the audience to know that the artist Donelle Woolford is fictional? Could she ever become non-fictional?

Feel free to answer or not answer any of these questions. Or, suggest other questions.

Email #2

From: stephen garrett dewyer

To: Group

Donelle Woolford’s performance of Dick’s Last Stand gives two acts of Richard Pryor’s career. In the first act, Woolford performs Pryor’s stand-up. In the second act, Woolford performs from Pryor’s 1977 television series called “The Richard Pryor Show,” which NBC heavily censored. The work pays homage to Pryor’s career by performing both the censored and uncensored versions.

I am interested in how DLS imagines the other becoming self and vice versa in a deconstruction of identity. For one, the work attempts to imagine alternate personas (Donelle Woolford acting Richard Pryor and Pryor's characters Mudbone and Miss Rudolph) as the artist in a process of de-centering the self to imagine the other-becoming-self and vice versa. Secondly, the work allows for improvisation on the part of the actors of Donelle Woolford to re-inscribe the role Donelle Woolford plays. Thirdly, the performance crosses institutional boundaries and cities to reach diverse audiences (fig 4).

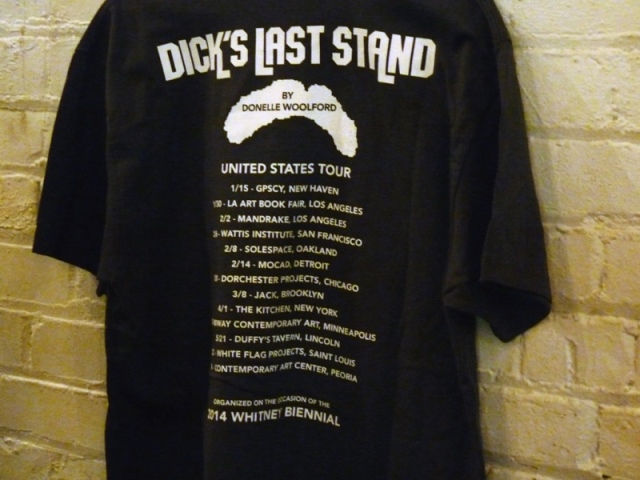

figure 4

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

I am also interested in the implications of the protests and rejections Dick's Last Stand received coming from a mostly African-American audience despite paying homage to Richard Pryor. For instance, the Studio Museum in Harlem refused to include the work, a professor of African-American studies called the work a travesty at the Oakland showing and an artist wearing only a paper bag on her head protested at the L.A. Art Book Fair.

To the roundtable: what do you think of Dick’s Last Stand?

Email #3

From: Greg Baise

To: Group

It sounds like a good start with these questions. I'm not sure how much I'll be able to contribute but I might chime in every now and then. A couple of things I do want to point out. First, the performance was one contiguous Richard Pryor performance, and none of it ever aired in the first place - the whole thing was censored. Also, I don't think it's accurate to paint protests as coming mostly from the African-American community, which implies that the community as a monolithic whole rejects this endeavor. The account I heard of the Oakland show said that a former Pryor comedy writer colleague was upset (he's the "first questioner" [and of unidentified race] in the Gallerist article), but other than that the performance was well-received, as Kidwell reports (fig. 5).

figure 5

|

|

Jennifer Kidwell (left) and Joe Scanlan (right) during the question and answer session after Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

Email #4

From: stephen

To: Group

as a clarification, I agree the protests didn’t come from a monolithic community. I wrote the “protests and rejections Dick’s Last Stand received c[ame] from a mostly African-American audience” and not the African American audience. I was referring to the fact the demonstrations I saw against DLS seemed to come from members of the African-American community and not the African-American community (as a whole).

Regarding the Oakland show, I was referring to the DLS performance at MOCAD where Joe and Jenn mentioned during the Q and A that a professor of African-American studies was outraged at the performance. I don’t doubt the performance was generally well received otherwise.

From my understanding, the “The Richard Pryor Show” aired for three episodes before NBC cancelled. The DLS performance at MOCAD performed two acts, the first almost entirely dick jokes and the second a bland and nervous Richard Pryor, which I assume was for the NBC audience (fig. 6).

figure 6

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

Email #5

From: Joe Scanlan

To: Group

Some information to help you move forward:

Dick’s Last Stand was formally turned down by five institutions, all contemporary art venues from every region of the country: northeast, south, midwest, west. Various reasons were given by all of them, all reasonable, as is the prerogative of any space responding to a cold-call proposal. Several others never responded at all.

Dick’s Last Stand, as you saw it performed at MOCAD, is based on a single, continuous performance by Richard Pryor before an assembled studio audience. As far as I know, none of it was ever broadcast by NBC, although it is available on a RP compilation DVD and on Youtube.

Email #6

From: Jennifer

To: Group

I'm interested in where the conversation lingered but am, at this time, finding myself uninterested in "who" is/was protesting Dick’s Last Stand, in part because I'm more interested in figuring out my own response to it first. On the other hand, I do think it's interesting that we did move right into a larger, broader audience response to DLS (other than our own), and one that was race-specific, rather than focus on what the work itself is/was. No judgement, just interesting and may be something worth looking at later on.

In response, I'm slightly concerned with using the word "homage" when describing Donelle Woolford's performance in drag of DLS as an homage to Richard Pryor. In conversations with Osman and through research it was brought to bare that Richard Pryor was quite misogynistic. In an LA Times article, even his daughter, Rain Pryor describes her father as such; "So yeah," Pryor writes, "he was misogynistic, mercurial, unpredictable and violent. But he was also my daddy" (Wiltz, Teresa. “Parented by Richard Pryor.” Los Angeles Times. 8 December 2006).

I did not find the performance of DLS specifically misogynistic in and of itself, but I'm sure that Woolford's re-enactment in drag is driving at something deeper than an homage. So, maybe we are reading the "gesture" of the performance inaccurately or without dimension. By selecting to re-enact a misogynist character in drag, I think Woolford is subverting Richard Pryor, among other things, rather than paying tribute or just shedding light on a subversive performance that was once censored. That said, for the die-hard Richard Pryor fans, maybe Woolford's subversion was taken as an insult or blasphemous to Pryor's legacy.

(Maybe it's not relevant for me to compare the Richard Pryor on stage to the Richard Pryor in “real” life? Does my doing so play further into the very problematic that the fictional character Donelle Woolford and her fictional career sets up?).

When I revisited the press release for DLS, it describes Woolford's new work as "cathartic" and "chronicl[ing] the place of honor afforded the male sex organ in American art and politics, and continues the oral tradition of phallic humor and innuendo in popular culture" (CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art . “Donelle Woolford." 6 February 2014). This leads me further to believe that there are not only issues of race at play but also of gender. Further on in the PR, it does state that "...Dick's Last Stand honors Pryor's brash political humor and marks its return to the live stage, where it's allegories on race, conformity, representation, and subterfuge are as painfully hilarious as ever." So, then again, maybe race is where we should keep our focus? I find gender a relevant topic that I'd like to discuss further.

I greatly appreciate the use of the word subterfuge here and find it relevant when looking for words to describe the gesture that is Donelle Woolford. But maybe subterfuge without malice (fig. 7), a soft subterfuge. Is that possible?

figure 7

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

Can you subvert and pay homage to the same thing at the same time? Does one negate the other? There always seems to be these oppositions co-existing in the work which I find quite brilliant and frustrating.

Email #7

From: stephen

To: Group

I think the question of whether Dick’s Last Stand can function as subversive while also paying homage to Richard Pryor is an interesting one. For one, what is DLS subverting?

That Donelle Woolford performs an homage to Richard Pryor as Richard Pryor suggests a layering of identity, one where the self (Woolford) performs an other that contradicts such a self. Here, the contradiction is a misogynist Pryor played by Woolford, who is female. Perhaps, then, the work is an homage to the difference that is Richard Pryor instead of simply Richard Pryor.

In Dick's Last Stand’s paying homage to the difference that is Richard Pryor, I believe the work subverts identity. As a subversion of identity, DLS seems to follow a perverted trajectory (which I mean as a complement). By perverted trajectory, I mean the work changes in contradistinction to an original intent. Such a trajectory seems also in contradistinction to the notion a work has to have a moral imperative.

The perverse operations in Dick's Last Stand seem to give the work a political dimension. The political, as Jacques Rancière writes, “cannot be defined on the basis of any pre-existing subjects. The ‘difference’ specific to politics, that which makes it possible to think its subject, must be sought in the form of its relation” (Rancière. Dissensus. p. 28). In the ways DLS shows the paradoxical performance of two seemingly contradictory subjects in one, the work seems political. Such a performance is visible in the performance of Woolford as well.

Has Joe created an entirely political work of art? I am not entirely convinced he has, since, as Rancière writes in his first of ten theses on politics: “[p]olitics, when identified with the exercise of power and the struggle for its possession, is dispensed with from the outset" (ibid. p. 27). While Jennifer (Kidwell) is able to improvise to some extent, she is an actor in a play directed by Joe. I have no doubt the work is a collaboration; however, to the extent an unequal power relationship exists in DLS, the performance seems to diverge from a political trajectory. To Joe’s credit, he does not seem to claim DLS to have a democratic intention. The issue of craft seems very relevant to Joe’s way of working.

Participants: stephen garrett dewyer, Jennifer Junkermeier and Osman Khan

Featuring after-dinner participation by Joe Scanlan

stephen garrett dewyer: To get us started, I had a couple of points I wanted to address. I am interested in discussing craft and how Joe defines it as persuasion. The craft of the work is defined as how well the work makes a persuasive argument. In some ways, I wonder if it's an art of persuasion. How believable is Donelle Woolford’s performance and, if such is the criteria, how does the work succeed?

Another point I want to discuss is the self and the other in relation to Dick’s Last Stand. In some ways, I found Joe's imagining of Donelle Woolford somewhat meticulous with respect to the making of another artist who is opposite his stature. In trying to imagine a polar opposite, Joe seems to occupy an almost objective position. Do you feel he is trying to create an objective portrait of Donelle Woolford or himself?

By objective, I mean: an accurate representation of this fictional character and how that character would become a believable individual within a society.

Osman Khan: For me it starts with an initial question Jennifer (Junkermeier) brought up which is "what is the gesture?" Before we even ask if it is convincing or not, we need to ask: what am I being critical of or judging?

What is the art work? Is it in the Dick's Last Stand performance we saw at MOCAD, or, the fictitious traveling character of Donelle? Where is the gesture? This is also true with other older work that Donelle has been presenting. Do you judge the abstract wood works that she's been making or do you say that is just a needed foil but the real work is this fictional character? That the wood objects are just needed in order to make the fiction work. It is a ploy. They work as ploy and plot in order to get the real work (the fiction of Donelle) to play out...

If I looked at the performance initially and, for arguments sake, say, I didn't know anything and just walked in, how would I evaluate what I saw in the live performance by Donelle that evening?

A black woman in drag re-performing a Richard Pryor stand-up... At face value, it was a good performance. The jokes are still good... Richard Pryor's jokes/anecdotes are still funny. She delivered them well. It made me laugh. On second glance, past the initial experience, what does it mean for a woman, particularly an African-American woman in drag, to do ‘dick’s’ jokes. Not just any jokes, but joke’s from someone who is an alpha-black male, successful, top of his profession, and more than slightly misogynistic... what does it mean for a black woman to re-appropriate this particular person and put it out again AND what do I think of that? Is Donelle critiquing or is she, herself, a critique.

Jennifer Junkermeier: I think it is impossible for us to look at this work and not consider the joke paintings of Glenn Ligon (fig. 8) or Richard Prince (fig. 9), both of whom I mention because I don't know if Dick's Last Stand makes sense without them. Art world references and context need to be part of the conversation.

Let’s consider the Richard Pryor appropriation in relation to Richard Prince vis-à-vis 1) Prince’s monochromatic Joke Paintings; 2) Prince’s collaboration with the late gallerist Colin de Land on the supposed creation of John Dogg, a fictional artist created to sell artwork created jointly by de Land & Prince and/or 3) the hyper-male and macho subjects of Prince’s work: cowboys (fig. 10), topless women on motorcycles (fig.9), car hoods and nurses (fig. 11) that seem to reinforce gender stereotypes rather than critique them.

OK: But I'm arguing a bit in abstraction. Let’s say, for instance, Dick's Last Stand is an African-American woman appropriating Richard Pryor. Now, you are right that there is a layer of art world context about appropriation, in general. In which case, Sherrie Levine is also a reference.

Joe Scanlan: Sherrie Levine’s photographs After Walker Evans, 1981 (fig. 6) would make a more accurate association, say, than her urinal, which is mostly about commodity fetishism and the reproduction of high class art history.

figure 12

|

|

Sherrie Levine

After Walker Evans: 4, 1981

gelatin silver print

12.8 x 9.8 cm (5 1/16 x 3 7/8 in.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

|

sgd: and Andrea Fraser.

OK: or even Abramović’s recent re-enactments. For a second, let's hold off on any racial or cultural overlays vis-à-vis Joe (Scanlan) and focus on Donelle and her appropriation of Pryor’s routine. Does it read as a feminist critique of black-male culture? Does the gesture, then, work similarly to the reappropriation of, say, terms like ‘nigga’ or ‘faggot,’ (fig. 13) i.e. a reclamation of someone and something disparaging and, through its re-uttterance, affords control over it?

figure 13

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

JJ: We would be amiss if we didn’t bring up Adrian Piper’s The Mythic Being performances (1972 - 1976) (fig. 14). For those performances, she dressed in drag, walked the streets and attended cultural events all while chanting “mantras” from a personal journal she kept since pre-adolescence. Piper described the mantras as, “selected passages expressive of some personal issue [she] was grappling with at the time. Repeating the passage was a way of defusing and transcending the issue. In this recording [she] rehearse[d] [her] repetition of the mantra of the month, with occasional Freudian slips” (Perform feminism. “Adrian Piper, The Mythic Being.” Bodytracks.org. 27 June 2009).

But my question still remains: would Richard Pryor have been somebody that the fictional character, Donelle Woolford, would have chosen without those art world references? If that was the only thing she was thinking, would there have been other characters or other personalities that would have specific subjects for Donelle to take and make those same points, or, perhaps, even more so?

OK: As opposed to Eddie Murphy or Chris Rock… So you are saying Dick's Last Stand creates a double entendre between Richard Prince and Richard Pryor. Dick Envy?

sgd: I don’t think Donelle has dick envy since her performance in Dick's Last Stand does not seem to compare her (absence of dick) to him (dick). The drag is critical of dick envy. DLS does seem to objectify Joe’s position, however, in his becoming a prop. The dick jokes Donelle tells about big dicks are in a bizarre and slapstick sort of way.

sgd: What do you think about Joe's performance in the Donelle Woolford performance? You could analyze Joe's performance as a prop maker. I look at the stool that he brought to Richard Pryor (fig. 15) that he made and it has an almost IKEA-esque style, which then replaces an Eames chair, which is the first seat that Pryor occupies. I am wondering if Joe sees himself as a prop maker in Dick's Last Stand and what, then, becomes of the performance.

JJ: I thought I read somewhere that Joe actually handcrafted the stool that Donelle/Richard/Mudbone sits on during the performance.

figure 15

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer

|

OK: That works if we relate it back to theatre where we have props, stagehands, a director, people required to run the show and actors. So, in a way, Joe is playing a lot of the roles in the production, just not the main character.

sgd: But does he have to do that to maintain his position as this director?

OK: Until you mentioned Joe making the stool, I didn't know it was his own artwork. I am not sure that it matters, unless the intent all along was for it to be artified. That is: to transform the prop into artifact by imbuing aura onto it through the performance, “it's the chair that was used in the Dick's Last Stand performance on which Donelle sat,” so now it's more than just a stool, and doubly more so that it was made by Joe (and as such precious) and passed off (fooled the crowd) as just an everyday prop (could have been from Ikea).

JS: I didn't make the stool, it was MOCAD's, but now I wish I had.

sgd: I feel Dick's Last Stand holds Richard Pryor in a venerable position. But I am wondering if the director of DLS (Joe) then becomes a prop.

JJ: Let’s consider Donelle’s work or the objects she is producing and calling her work.

sgd: She doesn't have a body of work. For me, it is the identity construction of the performance that makes it interesting. But the performance of Richard Pryor is an impersonation.

OK: What is hard for me is that the appreciation or critique can never be isolated to her work. Joe may argue against such a position, but to me the work is Donelle and not what Donelle makes.

JJ: But we can’t leave Donelle’s work out of it. To a certain extent it is only through her work that we have access to her. She only exists as an artist creating work and the only way we interact with her is on this premise.

OK: But in a way her work are only props to get the Donelle story across/out.

sgd: But such “props” museums include in exhibitions. I look at the props as possibly interesting sculpture but they use the ready-made in some cases, which are not really ready-mades since they are quite constructed by the artist. The props read as an extension of Donelle Woolford with Donelle an extension of the props.

JJ: Additionally, I think it is interesting to talk about the idea of "props" in conjunction with the 2008 traveling exhibition Double Agent (Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, Mead Gallery, Warwick Arts Centre, & Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead) curated by Claire Bishop and Mark Sladen where Joe Scanlan presented Donelle Woolford. For the show, he actually set up a studio space for Donelle (inside the exhibition space) where she comes in everyday of the exhibition and works in the studio producing these "props" or artifacts.

OK: The reason I'm using the word props as opposed to artwork or artifacts is going back to that original idea of how far does the fiction need to go for it to be credible, viable. And, of course, if Donelle is an artist, she has to make work, but it's a prop for the bigger fiction, right? A character in a story needs the right embellishments, a street to walk on, a house to live in, etc. which Joe is doing for Donelle through her making all the right props, exhibiting and performing, to make the representation credible. Maybe that is the way to look at it; and maybe that is the way in which we are supposed to understand Donelle. She is a rendered, literally fleshed-out character in a Joe Scanlan novel… and like any protagonist in a story, Donelle requires her own narratives, but ultimately a means to reflect Joe's own experiences.

JJ: You continue to bring up the idea of "his experience," which makes me wonder if we can divorce the idea of biography and its importance to informing the event and/or the artwork.

OK: But it has to be his experience… he's authoring it. Donelle’s narrative is steeped in art context and history, which is Joe’s world and experience not necessarily Jenn’s, the actress portraying Donelle.

Is Donelle Woolford a full-blown character that can really exist independently? I don’t or can’t believe so. She will always be a "creation" of Joe Scanlan. There is cooperation between the two— between the actors and director, but, she is not a "true" person because I always know that Joe is behind her. It's more like watching theatre that extends into the everyday. I believe Joe mentions something of the like in one of his interviews (Donelle as expanded theatre).

JJ: Joe does discuss the notion of "casting" in an interview with Jeremy Sigler (Sigler, Jeremy. “Joe Scanlan by Jeremy Sigler.” Bomb Magazine. 1 July 2010).

OK: Another way I thought about it, and, Jennifer, I believe you asked this question, "what is Donelle Woolford?" Is she a nom de plum?

JJ: Is she his alter ego? Is she a surrogate? Is she purely a representation, like you asked earlier stephen? Is she a metaphor? Or an archetype? A performance? A proxy? Osman and I also discussed whether or not she was a corporation.

OK: Or a collective?

JJ: A collective because there are five other actors who play/perform Donelle.

OK: Knowing a little more about Joe's role and his "props," maybe I can compare Joe and Dick's Last Stand with Malcolm McLaren and the Sex Pistols. McLaren was versed in the Situationist and creates the Sex Pistols out of the pervading zeitgeist, but the kids playing the Pistols are genuine. Arguably, he is behind the scenes making them rock and provoke the right way (it’s out of his and Vivienne Westwood’s shop they and other punks costume themselves). Kinda like how, in the end, Donelle has somewhat of an independent, though, scripted character.

JJ: That's interesting you bring up the Sex Pistols because 40 years later the exhibition Punk: Chaos to Couture (2013) is presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NY) showcasing Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood designs and the Sex Pistols clothing and ephemera.

sgd: In the interview with Jeremy Sigler, Joe talks about Donelle Woolford as an avatar.

OK: Yes, it could be an avatar. I can understand that, especially in the virtual world sense. Though typically an avatar tends not to have any independent intelligence, or autonomy.

JJ: But I think that Donelle Woolford has her own will too.

OK: It's hard for me to ever imbue Donelle with a persona. I don't believe the fiction enough. It is always Jenn (or others) playing Donelle vis-à-vis Joe. I don't think she has a separate personality. She is not fleshed-out enough for me to "believe" her independence. At some point, it might have been, but now that narrative is too lost to me.

JJ: But she is old! She has been around for 10+ years. And she developed as Joe continues to work with some of the same actors. The longer Jennifer Kidwell gets to play Donelle Woolford, the further her version of Donelle develops and takes on a life of its own. She drives the character different places, different directions, however/wherever she feels like she should go.

OK: I'm curious to ask if both of you as well feel comfortable saying Donelle the artist did this? I don't.

sgd: For me there are always parentheses present. Such as Joe Scanlan parentheses Donelle Woolford or Donelle Woolford parentheses Joe Scanlan. In some ways, Donelle Woolford is a very one dimensional character. She is the rising art star and it's very imaginable that she exists, but it isn't what is happening with Donelle Woolford.

OK: The layers of fiction in this performance are clever. They are still problematic, but it's clever; a fiction of a fiction of a fictional character.

JJ & sgd: Yes.

JJ: I am interested in things both Jennifer (Kidwell) and Joe said about dealing with opposites. Specifically, I am interested in what they said about black and white just happening to stand-in for polar opposites and not the color of one’s skin. There are always these opposites that are negotiated where thinking of the "other" is not purely a representation of race.

sgd: I remember that discussion about opposites, which seems like a deconstruction of identity. As a piece, Dick's Last Stand seems about deconstructing identity.

JJ: But whose identity are we deconstructing? It's not a specific identity. It is not black identity, white identity or brown identity… for me it is a larger understanding and, well, taking away the myth of an artist biography and how that affects how we look at/view the work.

OK: Yes, that's one reading, but you can read it another way. Specifically, what happens when a black woman (in drag) appropriates a black man’s jokes? And, then, what does it mean for a white man to USE said black woman (in drag), to appropriate a black man’s, Richard Pryor’s jokes? If I can argue that in Donelle’s reenacting Pryor’s work, she, in essence, also disarms his potency and emasculates him (or at least what he stands for). THEN, in fact, and this may be a very ‘Eating the Other’ (hooks. “Eating the Other: Desire and Resistance” in media and cultural studies: keyWorks. 2006) (fig. 16) way of seeing this, Joe (a white man) as the main instigator of this performance, has essentially enabled a way to neuter the black man, i.e. ‘dick’ envy solved by proxy castration.

sgd: interesting. I’m wondering if such a reading would take an essentialist position that only an African-American man can tell Dick Jokes as told by Richard Pryor. What I find interesting are the unexpected turns in representation in DLS where the other and self blur together. Where Joe's role ends and Donelle's begins seem very clear in the sense that the play doesn't continue without Joe. However, not at all clear to me whose responsibility the play has in the end.

I understand that you are also talking about castration, but I also read DLS as a continuation of an homage to Richard Pryor in the sense that it is still funny that Joe and Jennifer (Kidwell) are almost doing Richard Pryor a service, although he is no longer here. In some ways, such an imitation is a form of flattery. I see the imitation of Pryor as a continuation of Pryor’s career and his performance, which becomes both a castration and continuation.

OK: Why does Joe have Donelle choose Richard Pryor and not Lenny Bruce or Andy Kaufman? Why not perform it himself? Even though they disseminated a perverted culture of “black,” one wouldn’t call Blackface minstrel shows homages… not to equate the two but I ultimately find this aspect of Joe’s gesture extremely problematic.

JS: Jenn first proposed reenacting the Richard Pryor stand-up. I think that has an interesting relation to the earlier discussion about what is Donelle, because the prospect of performing Dick's Last Stand was introduced by one of the actors. Yes, as the director, it was still my responsibility (authority) to accept or reject the proposal, but for me this moment is when Donelle Woolford really became a collaboration and/or a collective. An actor was not only participating in the project, she was actively bringing new content to it.

sgd: for me, in choosing Richard Pryor, the works becomes a (re)presentation of how we are mutually implicated in the production of self and the other. In order to imagine such a relationship, the performance has to imagine the other as well as the self simultaneously. In trying to imagine both, I find Dick's Last Stand a blurring together of identity in such a way where ignorance of the other becomes undone. At the same time, it is not really a secret. It is still his construction. I find DLS interesting because it counters the ignorance of the other in self-representation and how any construction of the self also creates an other (fig 17). If we don’t talk about such a relationship, silence becomes the norm for how we affect each other.

figure 17

|

|

Donelle Woolford

Dick’s Last Stand, 2014

MOCAD

14 March 2014

photograph courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

OK: I find no access to this blurring in Dick's Last Stand. I do not find Joe refracted in Donelle or her act, I just see the constructed other and an opaqueness that refuses to reflect the relationship between players, which depending on your lens is either poetic or problematic.

JJ: We discussed this idea: that since I'm white I can't talk about black issues.

OK: Or, you can, but only safely vis-à-vis your own condition.

JJ: But Donelle Woolford allows leeway and access that Joe would not have otherwise. I think Joe uses the word "qualify” in his interview with Jeremy Sigler. But what "qualifies" someone to talk about this issue or that issue?

OK: He has every right to talk about any, including black issues, but again only vis-à-vis his own situation. Otherwise, it becomes problematic. This is again where clarification of the relationship of Joe, Jenn and Donelle becomes important… Is Jenn providing legitimacy to the blackness of Donelle?

JJ: But Jennifer (Kidwell) informs the character. Each of the actors informs where Donelle goes and what Donelle does.

OK: Okay... or is Joe deflecting any racial or gender criticism by exploiting Jenn’s blackness as a means to legitimize Donelle.

If we go back to this notion of who has or hasn’t a right to speak on behalf or for the “other”... an artist, any artist, must be allowed freedom/space to do this (or anything)… I feel Joe is brave to have done so BUT then you also must accept the problematics of the situation. My critique of Dick's Last Stand in respect to identity politics and representation is that it doesn’t address or confront the power and control structures that exist in the relationship between players (white vs black, man vs woman) and, instead, limits its critique to simply raising the problematics of representation.

sgd: well, representation has a lot to do with power. For instance, we may ask: does Dick's Last Stand step into stereotypes, or, rather, unravel such representations? Perhaps by making visible how we see each other, DLS deconstructs some of the barriers between self and other. But DLS also raise issues of self-representation, who can and who can't speak for a people.

OK: This is why Dick's Last Stand is more problematic for me than the wood abstract reliefs that Donelle was producing before.

JS: I agree. Dick's Last Stand springs from a series of attempts by the actors and me to address the what- or who is Donelle Woolford question. The problematic begins as soon as I cast a real, live person to stand in a gallery where artworks are on display who says, “these are mine.” The problematic intensifies when that person is a black woman, true from the very first performance by Jenn at Wallspace in 2007. Part of the problem stems from what we normally do as artists at our openings: we stand there, we greet people, we maybe talk about the work but probably not unless a stranger asks a question. Not terribly compelling theatre. So the first time Jenn performed this—standing, greeting, talking—her and I were ostensibly the only people aware that a performance was taking place. Not only was there no fourth wall of the theatre, there was no third or second or first wall either. We thought of the walls of the gallery as being the limits of the theatre and that everyone present was on stage, but people weren’t much persuading of that being the situation.

But the real problem was the fact that I, a white man, had put her, a black woman, there. Because of the power relations involved, it didn’t matter whether we thought we were doing theatre or not, whether Jenn had agency as an actor, or whether her portrayal of an artist at her opening was entirely accurate.

Ever since, we have strived to make it somewhat clearer that what people are experiencing is a construct, a theatrical production, but we also try to preserve some of the tension, the ambiguity. The artworks became sets, and the actors performed choreography (Long Crosses, 2009) or loosely scripted dialogues (Dan Graham Withdrawal Syndrome, 2009) in them. Ultimately we developed a stand alone performance, a reenactment of Dan Graham’s Performer/Audience/Mirror (1975) but with two performers—Jenn and Abigail—going through Graham’s original iterations but out of sync with each other, like singing a round. All three performances entailed the increasingly collaborative nature of Donelle Woolford and foregrounded the performance side of the project, in which the actors know more about the situation and have greater authority than I do. DLS is the apotheosis of this dynamic, since the transcript clearly calls for my characters to cede authority to Jenn’s character.

But the problematic remains to a much greater extent in art than it does in music or theatre, or even film. To me, this is the most interesting of all the questions Donelle Woolford raises about art.

OK: For me, initially, the creation of Donelle has potential as provocative critique to and of the art world. That is: it asks the question, what does it take for a young, black woman to be successful. The right bio, check, born in Detroit, the right school, check, Yale, mixed with atypical work, initially abstract assemblages as opposed to identity politics. Her success or failure on her own terms would have been interesting but this particular critical narrative for me gets clouded by the fact that her success (for example, her inclusion in this year’s Whitney Biennial) is absolutely predicated on Joe’s existing success and networks.

JJ: In this discussion of biography, I would also like to point out that Donelle was not “actually” born in Detroit. In her online bio we find that Woolford was really born in Conyers, GA, but later changed her bio to read that she was born in Detroit, MI. I’m interested in discussing what that means.

OK: I like that he has Donelle mess with her biography and that she is not very scrupulous. She’s not above working and playing the system. Rewriting their story so they get the better narrative, they have the right cred, the right mythology...

JJ: But my question is, specifically: why did she or he choose Detroit in altering Donelle’s bio?

OK: Well, which city in America has one of the toughest creds? If you were raised in NYC, with two professors as parents and end up going to Yale: there is no story there. To say you were raised in Detroit or were born in Detroit and then went to Yale: that’s considered success. In returning to Beuys and myth making, Joe’s role in the creation allows the fiction to slip into farce, which is poignant and critical in its own way but also takes a bit of the bite out of Donelle as an independent actor for critical engagement.

sgd: The institutional critique aspect of DIck's Last Stand reminds me of Michael Queenland (fig.18), who hates institutional critique. I think for Queenland, he is not interested in institutional critique because, in his view, it is a choice whether or not to show at an institution or at a gallery and, so, then, to critique the institution would critique one’s own choice. And, why critique your own choices?

figure 18

|

|

Michael Queenland

Rudy’s Ramp of Remainders, 2013

Santa Monica Museum of Art

photograph by Monica Orozco

|

OK: So, he’s saying if you are not happy with America, rather than be critical, leave? But who else then does the critique? If you are outside of an institution, your critique ends up being labeled as bitter. Like what just happened to Maximo Caminero, an artist in Miami who broke the Ai WeiWei vase. I didn’t see much praise for his action just admonishment (even from Ai WeiWei).

JJ: Sadly, Caminero didn't know the vase cost a million dollars or he claimed he didn’t.

OK: And, then, Ai Weiwei's response was really pissy. I didn't like the way he responded. He should have come to the artist's defense. Everyone comes to Ai Weiwei's defense. Weiwei argued it wasn't his "property" and so forth. So, there's a guy who is doing institutional critique, supposedly, but, unfortunately, it was played-off as a whiny local artist. If (the current) Ai WeiWei had smashed a Chinese vase at the Met, I am sure the response would have been different.

But let's return to Joe. To me the institutional critique of creating an artist who's successful would be much stronger if Donelle was successful in a way that Joe wasn't. For me, then, it would have teeth. Joe is pretty successful and has the network to set up Donelle very quickly in the art world.

JJ: But how would we define that success? By Donelle becoming the ultimate art star? How would that success play out to our satisfaction as to do something that Joe couldn't?

sgd: To his credit, Joe is in this position where he's done very well but at the same time has remained very contentious.

JJ: Another question I want to ask is how we feel about using other people as a medium for an artwork? We haven't spoken of exploitation at all, which maybe we don't need to discuss?

OK: Maybe we can start by looking at two extremes of artists using ‘people as a medium.’ One extreme is Santiago Sierra (fig. 19).

JJ: I knew you were going to mention him.

OK: I'm going to mention him because people have a lot of issues with the work. Often, the critique of much of his work is that it is exploitative. Yes, it is exploitative, but so is capitalist labor. He's exploiting what capitalism tends to exploit anyways. I say you can never put a moral clause on art, on the artist perhaps but not the artwork. For me, art has no morality.

sgd: I agree with you about art not having morality, and I'm really not into "good" art. My issue with Santiago Sierra’s work is his failure to accept that he has some agency in his work. He's saying ‘this is what you are already doing and I'm just showing it to you, but I'm not responsible for any of it,’ which is a postmodern stance. Sierra’s work reflects capitalist society as it sees itself with no one taking responsibility for any of the actions that happen within that system. It's super, super unimaginative what he does.

OK: The counter example I want to bring up is Francis Alÿs. In particular, I’m thinking about Cuando la fe mueve montañas/When Faith Moves Mountains, Lima, Peru, 11 April 2002 (figs. 20 - 21). Interestingly, the word exploitation is not used to talk about the work. Rather, terms like communal, participatory… are used because they are performing a poetic and “romantic” act, even though they are also asked to labor for something just as absurd and futile as Sierra’s gestures. Is it also because Alys is also a participant...

Here, I’d return to Joe and the original question of whether or not the gesture of Donelle Woolford and Dick's Last Stand is exploitation or not. In reference to Joe and Jenn (Kidwell), I would never use the term exploitation within the context of DLS.

1 not everyone invited to participate in the round-table discussion participated.

CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art . “Donelle Woolford: Dick’s Last Stand: A reenactment of a stand-up by Richard Pryor realized on the occasion of the 2014 Whitney Biennial.” Press Release. 6 February 2014. http://www.wattis.org/calendar/donelle-woolford-dick%E2%80%99s-last-stand

hooks, bell. “Eating the Other:Desire and Resistance” in media and cultural studies: keyWorks (revised edition). Edition by Meanakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas M. Kellner. Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.: Malden, MA; Oxford, U.K., and Victoria, Australia. 2006: pp. 360 - 380

Perform feminism. “Adrian Piper, The Mythic Being.” Bodytracks.org in conjunction with a live event at Tate Modern on 27 June 2009. Organized by Oriana Fox in conjunction with The Women’s Art Library Make Archive held at Goldsmith’s College, London. 2014. http://bodytracks.org/2009/06/adrian-piper-the-mythic-being/

Rancière, Jacques. Dissensus: on Politics and Aesthetics. Edition and translation by Steven Corcoran. continuum: London and New York. 2010: p. 28

Russeth, Andrew. “There’s Something Funny About Donelle Woolford.” Gallerist. 3 March 2014. http://galleristny.com/2014/03/theres-something-funny-about-donelle-woolford/

Scanlan, Joe. Things that Fall.

http://www.thingsthatfall.com/

Sigler, Jeremy. “Joe Scanlan by Jeremy Sigler.” Interview with Joe Scanlan. BOMB Magazine. 1 July 2010. http://bombmagazine.org/article/3580/joe-scanlan

Wiltz, Teresa. “Parented by Richard Pryor: Rain Pryor’s ‘Jokes My Father Never Taught Me’ is a love letter to her complicated dad.” Los Angeles Times. 8 December 2006. http://articles.latimes.com/2006/dec/08/entertainment/et-pryor8 |