Introduction

What is a book? This essay is about The Open Book Project, a four-part collaborative project produced by Ryan Molloy and me. Our intention is to challenge notions of what books can be and to promote further discussion about the culture, legacy and future of books.

Most traditional books contain texts that are printed in black ink on white paper and are then bound in codex form. Most people who read these sorts of books gloss over their visual and sensory qualities, such as the dimension and heft of the volume, the texture of the paper, the character of the typography and the black ink of the letterforms against white paper. Reading any sort of book, though, goes beyond just accessing text on the page; it is simultaneously a textual and multi-sensory experience. What can be gained by making people aware of this total reading experience? Understanding that reading is a sensory experience is essential to grasping ideas about the future of the book.

The Open Book Project—which includes an exhibition of experimental books, an immersive experimental book workshop, a special issue of the British journal Book 2.0, and The Open Book Project book—proposes that the textual information books carry can’t be separated from our experience of the book as a visual and physical object. The typography, imagery, color, materials, texture, format and other physical, non-physical or digital qualities of books add meaning to their content. Like the substance of the written text, these qualities participate in the experience of reading any book.

The Open Book Exhibition

My colleague Ryan Molloy and I both love books. We both love how they feel and how they function. We enjoy how type, content, materials and imagery come together to create a filmic sort of narrative that often opens with the front cover and ends with the back cover—if that’s the way the book was designed and the user chooses to experience it. We both also love books that push against established boundaries for format, medium and form. The notion that print books are totally obsolete, and that they’re in the midst of being superseded by digital books, doesn’t make sense to us. Neither does the idea that e-books are a menace that has destroyed the future of print books. Our anecdotal experience with older forms of media being “usurped” by newer ones suggests that such transitions are typically more tangled than clean.

We found allies for these ideas in the fascinating book Rethinking Media Change(MIT Press, 2004). Authors David Thorburn and Henry Jenkins take umbrage at what they call “contemporary doomsayers” who proclaim that digital technology unequivocally guarantees the end of the traditional book. Even more interesting, Thorburn and Jenkins warn that by glorifying new technology and dismissing old technology we miss out on compelling hybrid forms that come to light during times of media transition (2004, 3).

Our love of books and our desire to push back against “media fanaticism,” plus our fascination with the exciting hybrid, collaborative forms that may come out of very messy media change led directly to the Open Book exhibition, which ran at Eastern Michigan University’s (EMU) University Gallery from April 5-June 15, 2010.

When we began curating the exhibition we asked ourselves: what sorts of objects can books be? Despite—or maybe in reaction to—the recent claims that print is dead, designers and artists have embarked upon a passionate exploration of books as physical objects, as hybrids of physical and digital media, and through digital media alone—just as Thorburn and Jenkins argue! We chose work for the Open Book exhibition that both probes the relationships between the materiality and the dematerialization of the book, and that foregrounds the relationships between the form of an object and the information it delivers.

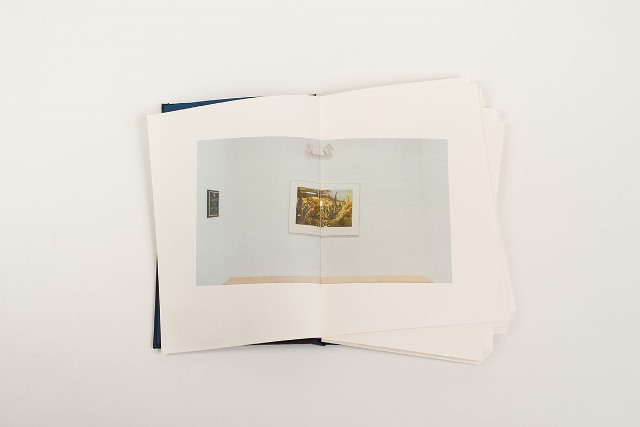

Loosely defining books as objects that organize written, verbal or visual content into two or more sections, the goal of our exhibition was to encourage exploration of the unconventional forms books might take (fig. 1).

Our definition of books seems to suggest that anything can be a book, but we certainly didn’t curate that way. Ryan Molloy and I had something else in mind that delimited this definition. The word “book” suggests some common terms: printed, bound, glued, sewn, illustrated, written, hinged, fastened and so on. Books have structural components such as words, images, pages, sections, signatures, indices and volumes. Content is important: written or illustrated content, narrative content, a record, a list or a register. The pieces in the Open Book exhibition that seem to embrace “it’s a book because we call it a book” retain characteristics that are found in traditional book terms and structures.

| figure 1 |

|

| Gallery Photos, Open Book, University Gallery, Eastern Michigan University, April 5-June 15, 2010 |

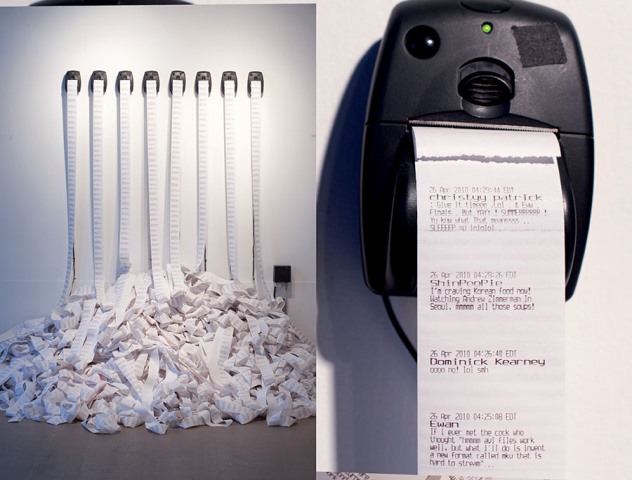

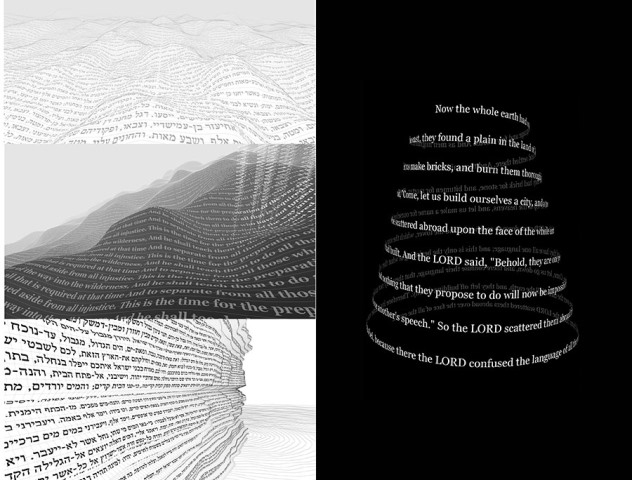

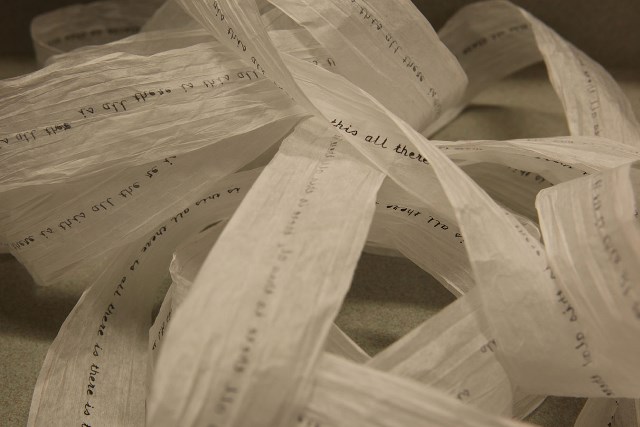

Chris Baker’s Murmur Study (fig. 2) monitors Twitter and prints tweets that have emotional utterances, such as argh, meh, grrrr, oooo, ewww. The tangled piles of printer paper can be seen as a contemporary scroll, a printed register on paper. Susan Carr’s China and White (fig. 3), two pieces that document her life experiences,are sewn or bound and contain text. Ariel Malka’s Javascriptorium and Babel Tower (fig. 4) are digital adaptations of “the book.” In Javascriptorium, we “read” lines of text from a moving 3-D rendering that’s projected onto a 2-D space instead of reading lines of text on a page. We see the ancient Hebrews wandering in the desert as text from Exodus, for example, in a projected, scroll-like format.

| figure 2 |

|

Christopher Baker, Murmur Study, live Twitter feed, thermal printers, custom hardware, dimensions variable

|

|

Susan Carr, China, wire, paper, pencils, jade, metal, found objects, 63" x 6.25" and White, wire, wood, paper, ink, string, 21" x 5.5"

|

|

Ariel Malka, Javascriptorium, video

dimensions variable (left) and Babel Tower, iPhone/iPod touch app, 3.4" x 2.4" (right) |

Books are frequently thought of as objects of intimate experience, but this is only one way of experiencing books. The Open Book exhibition presents work that must be viewed from several feet away and close up, as in this piece by Edwin Jager called Liquid into My Skin (figs. 5 & 6). He uses old technology—35 mm slides and 19th-century magic lantern slides for his piece. Doug Beube’s piece Vest for the New World (fig. 7) also needs to be taken in both close up and from a distance. Certainly, a number of the in Open Book need to be experienced intimately. But their inclusion in a gallery with a range of other book formats—all of which are viewed by dozens of participants milling about—challenges the paradigm of books as simply intimate objects, and demonstrates that books can function in a variety of forms and fashions.

| figures 5 & 6 |

|

|

Edwin Jager, Liquid into My Skin and close up, 920 35mm slide transparencies, 12 3.5” x 4” antique lantern slides; fluorescent and halogen lighting fixtures; wiring, dimensions variable

|

| figure 7 |

|

| Doug Beube, Vest for the New World, altered encyclopedias, wire, wax, metal, vinyl, zippers, binding, thread, 21" x 20" x 5" |

The Open Book exhibition included unique printed books, altered books, and sculptural books made from a variety of materials, such as this book by Jacqui Rush Lee (fig. 8). It also included digital books, projected books, and installation-, photography-, and performance-based books (figs. 9 - 11).

| figure 9 |

|

Jacqueline Rush Lee, Cube, (from the Volumes Series)soaked, dried, assembled books, 1' x 1' x 1.5'

|

| figure 10 |

|

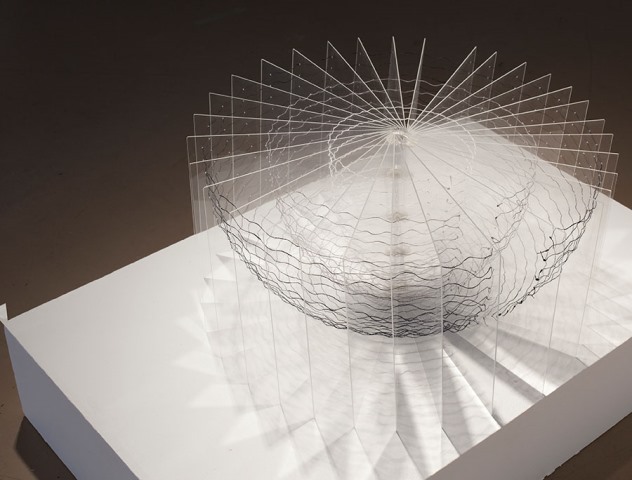

Janis Nedela, Palindrome No. 23 (Sator Arepo Tenet Opera Rotas) laser etched acrylic, paint, diptych, 8.25" x 5.5" x 1.25" and Adele Outteridge, Vessels, perspex and thread, 11.8" x 11.8"

|

| figure 11 |

|

Adele Outteridge, Vessels, perspex and thread, 11.8" x 11.8"

|

| figure 12 |

|

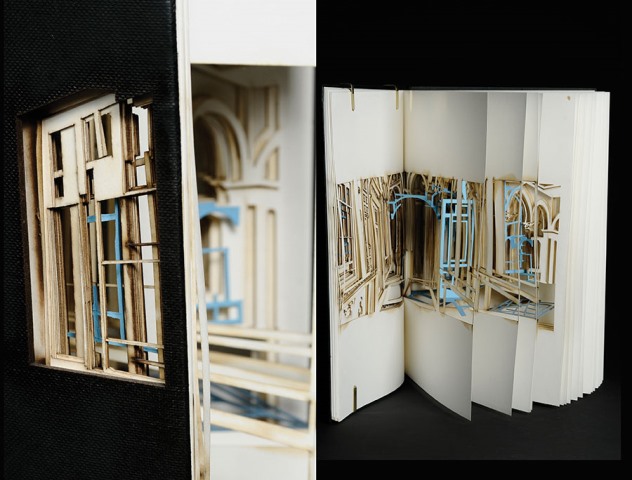

| Johan Hybschmann, The Winter Palace, laser cut book, 12.6" x 14.6" x 13.77” |

These media experiments give the audience novel ways to reconsider the traditional book as a physical, three-dimensional object. Doug Beube's book that’s made of maps and zippers (fig. 13), for example, offers us an interesting way to think about books as sculptural objects; at the same time, he creates a system for building a book—the "pages" can be reorganized, reattached, reconfigured and reassembled.

| figure 13 |

|

| Doug Beube, Border Crossing: In the War Room, altered atlas, zipper, 19" x 22.5" x .5" |

The Open Book Project Workshop

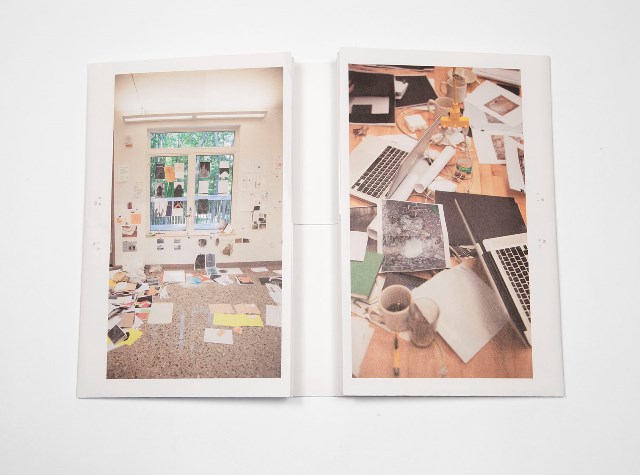

After the exhibition, we wanted to continue our investigation of the book. We’d already run one immersive summer experimental book workshop at Eastern Michigan University’s rural Parsons Center in northern Michigan in 2011 and we got a grant to run two more workshops and to produce a book about the project. The Open Book Workshop, which is held in the middle of the woods at Eastern Michigan University’s Parsons Center in northern Michigan, sequesters participants in a remote, rural location for ten days so that they can immerse themselves in ideas about books (fig. 14). Open Book is a sort of artists’ residency. There is equipment on site—the participants bring materials to use and share. The creative energy, though, comes from the group dynamic. The participants work with two visiting artists or designers who lead the group and encourage participants to explore two deceptively simple questions: “what is a book?” and “what is the book?”

| figure 14 |

|

| Eastern Michigan University, Jean Noble Parsons Center, Lake Ann, Michigan |

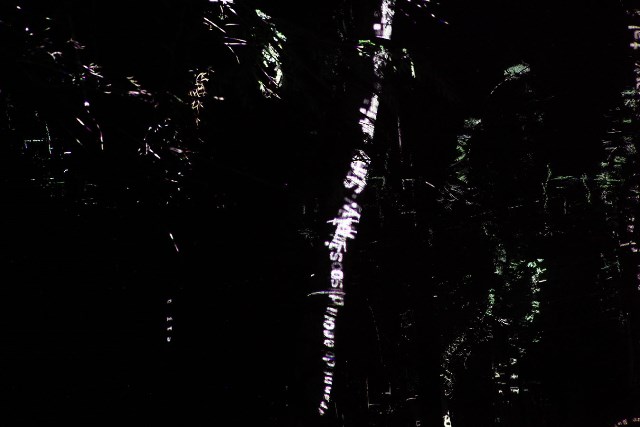

Each visiting artist sets up unique parameters for exploring these two questions. In summer 2011, the first Open Book Workshop group responded to these questions by examining frameworks by which we experience and structure books. For participant Sara Brandys, books became an immersive video environment (fig. 15). She projected moving poetry about the frailty of the body among the trees at night. The trees reference life, but also the wood from which paper is made. The text is a variation of the common black text on white background. There were also screen-based video pieces, typewritten books and books made from found objects (figs. 16 & 17).

| figure 15 |

|

Sara Brandys, Open Book Workshop, summer 2011

|

| figures 16 & 17 |

|

|

| Various projects, Open Book Workshop, summer 2011 |

In year two, summer 2012, the theme was the cultural roles that books play. This group of participants considered library structures and functions, distribution networks, the production of materials, and book culture. Participants were asked to produce an edition of “books”— one copy for each participant—a parameter that had a significant impact on the individual work that was produced. Instead of exploring only the book itself, participants had to consider the commerce or sharing of book-like objects. One participant, John P. Corrigan, for example, created a narrative spread across a batch of fortune cookies for the group (fig. 18). Another participant solicited others to help modify a t-shirt guided by the question “how is a t-shirt like a book?” (fig. 19).

| figure 18 |

|

Fortune cookies as a book edition, John P. Corrigan, Open Book Workshop, 2012

|

| figure 19 |

|

| Various projects, Open Book Workshop, 2012 |

In 2013, participants turned their attention to the contents of books. These participants curated, organized and analyzed their surroundings in order to create encyclopedic volumes about one of their on-site experiences (fig. 20). One project included a rigged up device that translated the sounds in an audio file that was created in the environment into pen and paper drawings (fig. 21). Another included an obsessive examination of a crookedly hung photograph, and yet another was a video of a book made by the participant in which dirt from the site is pitched onto its pages (fig. 22).

| figure 20 |

|

Haynes Riley and Michael Demps, Open Book Workshop, 2013

|

| figure 21 |

|

Lily Sun, Open Book Workshop, 2013

|

| figure 22 |

|

| Paul Goodrich, Open Book Workshop, 2013 |

In summer 2014, participants did weeklong fieldwork at the Parsons Center (fig. 23). They generated field notebooks, gathered materials and took turns doing site observations at the dock at the lake on site over 24-hours that led to the creation of a “jump-kit” of the observations (fig. 24). The term jump kit (or jump bag) is a kit that is needed in order to do some sort of fieldwork. All of the items that were used during the 24-hour observation at the dock were collected along with field notes and put into a custom box, which became a sort of “jump kit” for the future.

| figure 23 |

|

Field notebooks and various gathered materials, Open Book Workshop, 2014

|

| figure 24 |

|

| Jump kits, Open Book Workshop, 2014 |

The shared attempt to answer questions about the book generates a close-knit community among Open Book participants that adds to the immersive quality of the experience. The participants work, cook and eat together, (fig. 25) and they share their unique abilities when they create books together. It’s through this complex act of making that participants create new notions of books.

| figure 25 |

|

| Dinner, Open Book Workshop |

The questions that are posed at each workshop remain largely unanswered. The accumulation of what workshop participants think and do each summer, though, builds a rich sense of what books may be, what they have been, and what they can become. It’s in the absence of clear answers to a range of questions that the Open Book Workshop becomes a proving ground for The Open Book Project, making it clear that there’s still plenty of fertile territory to explore when it comes to books.

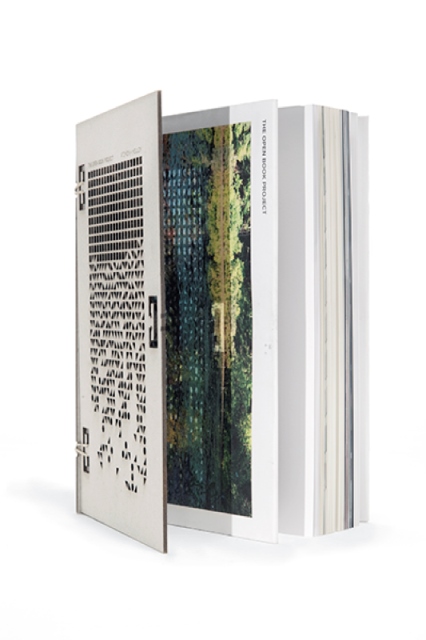

The Open Book Project Book

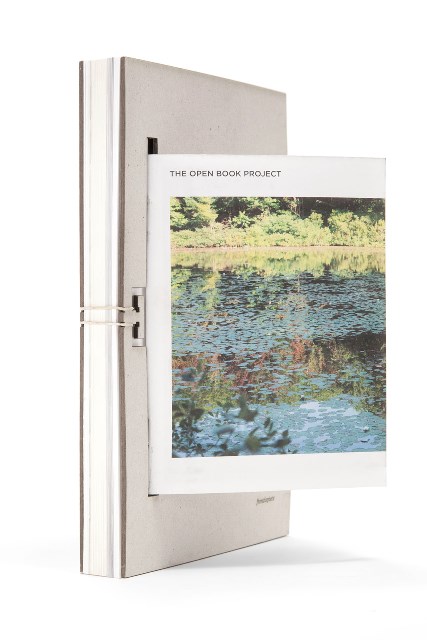

In 2013/2014 we began editing and producing The Open Book Project book. The book brings together a catalogue of the exhibition, information about the workshop and visual and critical essays (fig. 26). We art directed the whole book together, I edited the book essays and wrote the critical Introductions to the essay section and the catalogue, and Ryan designed both the perfect-bound (paperback style cover) and laser-cut book covers. Our goal wasn’t to create a radical book; instead, we wanted to reconsider traditional book forms and media in subtle ways.

| figure 26 |

|

| The Open Book Project book, 2014 |

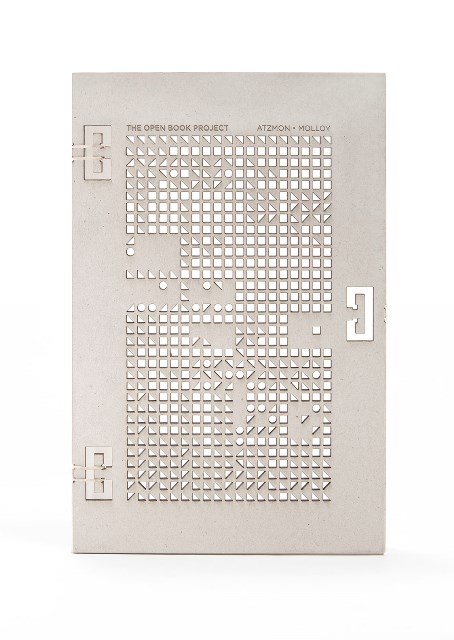

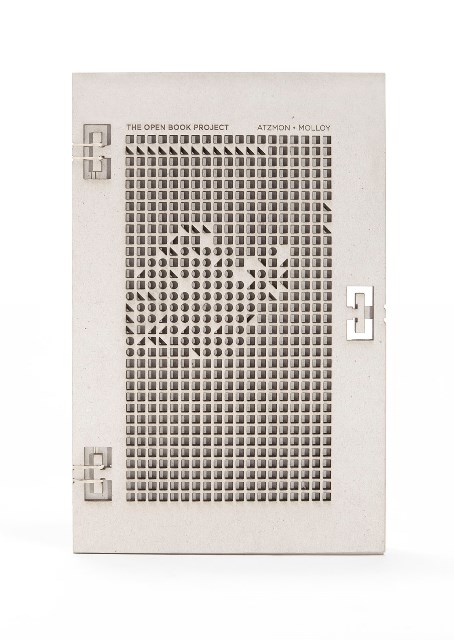

The basic book is a perfect-bound book. We decided to take book board, which is normally hidden under book cloth in case-bound books, and reveal it as a kind of exoskeleton that goes over the perfect bound cover (figs. 27 & 28). Ryan wrote a program that translated photographs we took at the workshop into a symbolic language of circles, squares and triangles that made their way onto 50 different cover design variations. The geometric shapes were laser cut into book board and acrylic and the laser-cut covers are bound around the perfect-bound book cover using rubber bands.

| figures 27 & 28 |

|

|

| Various laser-cut covers, The Open Book Project book, 2014 |

This was a digital/physical hybrid process: we used a computer program to translate images into geometric symbolic language laid out in digital files. These digital files were then laser cut into physical materials—book board and acrylic. The laser-cut and perfect bound covers also reference decorative book cover design. The rubber bands are interesting binding material because they are every-day objects that have to be stretched and threaded through the front and back covers. They need to be replaced after a time, which reminds those who use the books once again that they are physical objects.

We worked closely with a student who designed the promotional material for the 2013 workshop on the design of a dust jacket for the book. The dust jacket—which goes over the perfect bound cover and under the book board covers—opens to a poster and can be cut up and saddle stitched using directions we included at the end of the book to create a separate little book about the workshops (figs. 29 - 31).

| figures 29 - 31 |

|

|

|

| Dust jacket, that converts to a poster and can be trimmed and folded into a booklet, The Open Book Project book, 2014 |

Book Interior Design

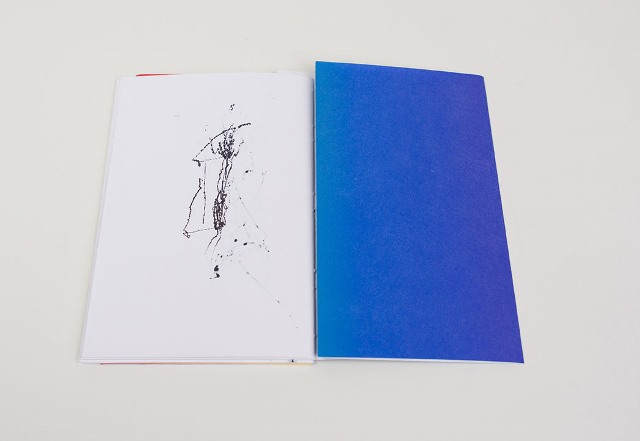

We decided, in light of our ideas about involving others in the concepts behind The Open Book Project, that we should crowd source seven of the eight essays in The Open Book Project to designers who’d been involved in the Project. The eighth piece is a fully designed visual essay by designer Denise Gonzales Crisp. We came up with specific parameters for all of the designers: specific type families, 6" x 9" page measurement, no bleeds, minimum 1/2" margins on all sides, etc. We assigned the seven essays randomly and gave the designers three to four weeks to get us their designs. We didn’t know how the essay designs would turn out and none of the designers knew how the other essays in the book would look. Scott Massey designed “The Book as Tunnel” by graphic designer and design historian Phil Jones (fig. 32).

| figure 32 |

|

| Phil Jones, “The Book as Tunnel,” essay designed by Scott Massey, The Open Book Project book, 2014 |

Considering Books

The Open Book Project's goal is to get past the simplistic thinking that sometimes characterizes discussions of the state of books. Books are crucial to the flow of information in our culture, so it’s surprising that there’s been little written that explores how books’ full range of traits—visual, material, conceptual, textual, sensual—come together to make meaning for their users/readers.

Some literary theorists, such as Gérard Genette, have moved in this direction. In his essay ‘Introduction to the Paratext’ (1991), Genette discusses how paratextual elements—which he defines as title, foreword, endpapers, colophon, footnotes, cover and cover art, design and typography—all add to the book content. Yet, even in Genette’s examination, the book text gets top billing; the paratextual elements, Genette explains, offer “a better reception of the text and a more pertinent reading” (1991, 262). Text and paratext remain unequal partners.

Graphic design writing about books, on the other hand, typically includes either how-to titles that outline book design processes or cool-looking book designs. The former mostly focus on traditional book design. Titles featuring experimental graphic design book projects usually consider projects content and concepts, but they typically don’t elaborate upon what such books say about what is happening to books today. Designer Irma Boom’s catalogue for an exhibition of her book design, Irma Boom: The Architecture Of The Book (Lecturis; 1st Thus edition, 2013), for example, features her unorthodox book designs. Boom’s are exactly the sorts of books that could provoke fertile conversations about the future of books both in graphic-design and non-graphic-design contexts. There also are few attempts to offer insights into the relationships between books as art and what books can be in publications on artists’ books. The small number of artists’ books exhibition catalogues mainly deal with the advent of the book as a contemporary art object.

It’s at once understandable and unfortunate that these three disciplines—literary theory, graphic design and artists’ books—have fundamentally discrete discourses about books, since the most fertile areas for creative dialogue are those spaces at which these discourses overlap.

Essay Content

Most of the authors in The Open Book Project book do both visual and written work. Johanna Drucker is a poet, typographer, book artist and scholar, Danielle Aubert is a graphic designer who specializes in book design, Phil Jones is a graphic designer and design scholar, Bonnie Mak and Julia Pollack are information scientists and artists, Denise Gonzales Crisp is a graphic designer and design writer and Tony White is a librarian, book artist, and artist book scholar. Penelope Umbrico is a photographer. Working in both written and visual media, these authors understand how both visual and verbal forms may come together in books to make meaning. It also helps them to imagine the myriad forms that books may take.

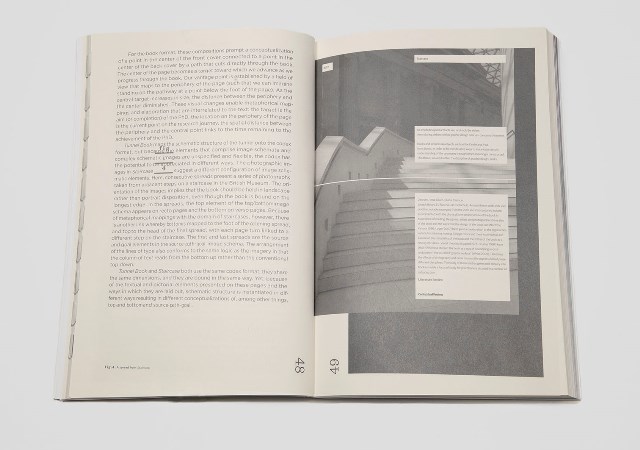

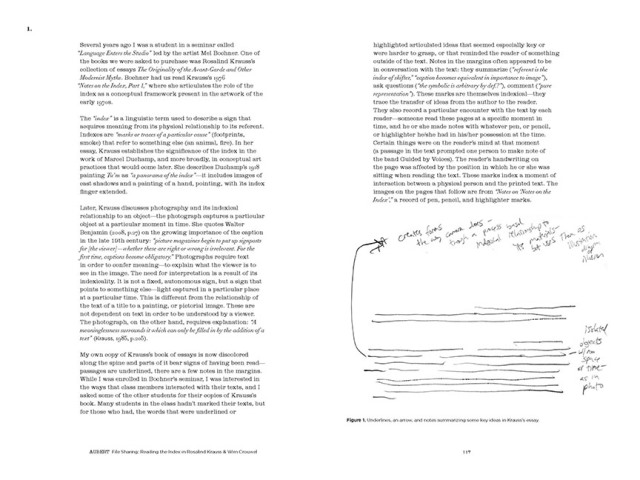

This article isn’t the right venue to describe every essay in the book. But we do want to take a few minutes to talk about a few of the essays. In “File Sharing: Reading the Index in Rosalind Krauss and Wim Crouwel,” Wayne State University Graphic Design professor Danielle Aubert begins her image-focused essay by citing the markings that Vladmir Lenin made in the margins of his copy of German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein’s book Philosophical Notebooks. Aubert argues that Lenin’s marks reveal a connection between reader and author; but Aubert is especially interested in how these marks demonstrate a connection between reader and physical text.

She uses this discussion as a basis to describe a graduate-school assignment in which her class was assigned art critic Rosalind Krauss’s essay “Notes on the Index, Part 1” (October. Vol. 3: Spring, 1977: pp. 68-81). Aubert explains that “index” is a “linguistic term used to describe a sign that acquires meaning from its physical relationship to its referent” (2013, 114). In other words, she explains, her fellow students’ marks and comments on their copies of “Notes on the Index, Part 1” are indexical; they are in dialogue with Krauss’s text. Aubert’s text supplements her imagery rather than the other way around (fig. 33). Her images are a fundamental part of her argument: “They trace the transfer of ideas from the author to the reader,” according to Aubert, and “They also record a particular encounter with the text by each reader” (2013, 117).

| figure 33 |

|

| Danielle Aubert, spreads from “File Sharing: Reading the Index in Rosalind Krauss and Wim Crouwel,” designed by Tuan Phan |

In “What is The Cult Future of the Book?” UCLA professor Johanna Drucker describes the awe that we have for digital media. She uses this characterization of the digital world as a springboard for a discussion of old media, in particular the awesome codex form of the book. She slyly insists that, measured against digital media, books “with their boards, cloth, and paper, have the rough-hewn feel of rustic objects” (2014, 70). She feigns distaste for traditional books, calling them “crude and clunky” (2014, 70). Digital technology, which typically relies on an elaborate infrastructure, Drucker argues in the end, is no less material than is print media. Drucker—like Ryan Molloy and me—is also skeptical of the traditional book versus digital format dichotomy. She concludes by asking: “Books of the future, future of books—how do we secure the place of humanity and human values at the core of a technophilic world?” (2014, 77).

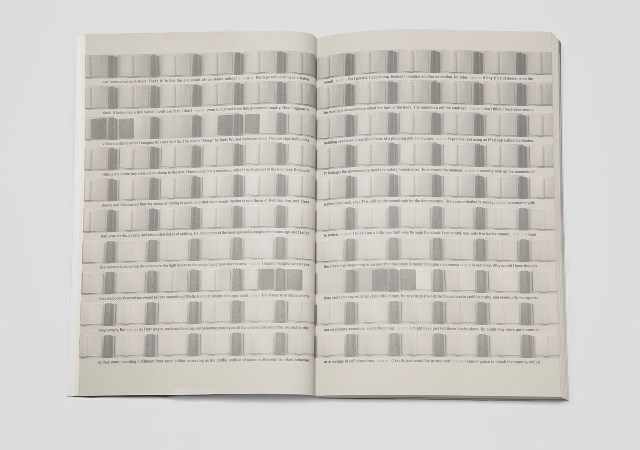

North Carolina State University Graphic Design professor Denise Gonzales Crisp explains that her visual essay, “Listening to Books,” “is… [an] attempt to read, or rather listen to, twelve blank books” (2013, 149). “Listening to Books” (fig. 34) is a series of photographs of twelve blank books taken every ten seconds over two and a half hours. She explains that “the project and the process serve… as a means to discover, and then to write about, how artists or designers interrupt book conventions” (abstract for special issue of Book 2.0, 2012). Gonzales Crisp rigs a system for photographing the twelve books and, then, begins to document the process in a photographic series of images and a train-of-thought series of words. She describes what happens next: “15:53:45 The apparatus swings slightly…The awkward set up and a shaky finger begin the discovery 15:55:30 and the shutter clicks audibly to remind me that I am now living in ten second 15:56:45 intervals, for the next two hours” (2013, 151)

| figure 34 |

|

| Denise Gonzales Crisp, Spread from “Listening to Books,” Book 2.0, 2013 |

The images of the books change as the light in the room changes, and Gonzales Crisp records both what she sees and what she thinks as time passes. The visual essay features Gonzales Crisp’s photographs in full-page spreads. She concludes her blank-book experiment with some disappointment: “Metaphors that attempt to capture the meaning of books abound…These twelve books resist such poetry. They are, after all, blank, and quite simply yield only the fact that they and I are here. Well, duh. Splendid idea, dumb ass” (2013, 154).

Conclusion

One intention of The Open Book Project is to encourage dialogue about hybrid or collaborative media recombination. This “dialogic, undisciplinary approach” encourages the exciting messy forms and receptive thinking that Thorburn and Jenkins argue happen during media transition (Atzmon, 2013, 94). Ryan Molloy and I believe that this unfettered thinking and making can foreshadow future forms books may take. Thorburn and Jenkins point out that this experimentation can be uncomfortable. They also note that, at times of change, “endangered” forms—such as books—seem to become “more visible and more highly valued (2004, 3-4).”

It’s clear that the notion of unidirectional transition from physical to digital books is both unhistorical and unproductive. In The Open Book Project, in contrast, Ryan Molloy and I suggest fertile ways to explore the book in an age of breathtaking technological change. When asked what our predictions for the future of the book would be, my collaborator Ryan Molloy responded “I don't think that there is any single answer…And the fact that we do not have an answer after four workshops, one exhibition, and a book is perhaps the best conclusion” (Heller, 2014).

Atzmon, Leslie and Ryan Molloy. The Open Book Project.

http://openbookproject.info/

Atzmon, Leslie, Guest Editor. 2013. “Introduction.” Book 2.0. 3.2: 87-95.

Aubert, Danielle. 2013. “File Sharing: Reading the Index in Rosalind Krauss and Wim Crouwel,” Book 2.0. 3.2: 113-120.

Boom, Irma. 2013, Irma Boom: The Architecture Of The Book (Revised & Augmented Biography Books In Reverse Chronological Order 2013-1986). Eindhoven: Lecturis.

Crisp, Denise Gonzales. 2013. “Listening to Books,” Book 2.0. 3.2: 149-162.

Drucker, Johanna. 2014. “What is The Cult Future of the Book?” In The Open Book Project, edited by Leslie Atzmon, 69-78, Eastern Michigan University, MI: Ypsilanti.

Genette, Gerard. 1991. “Introduction to the Paratext,” New Literary History, 22.2: 261-272.

Heller, Steven. 2014 “Writing the Book on Reinventing the Book.” The Atlantic, August 7. Accessed April 29, 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/08/writing-the-book-on-reinventing-the-book/375687.

Krauss, Rosalind. 1985. “Notes on the index: Part 1.” in Originality of the Avant Garde and Other Modernist Myths. 196–209. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Thorburn, David and Henry Jenkins. 2004. “Introduction: Toward an Aesthetics of Transition.” In Rethinking Media Change: The Aesthetics of Transition, edited by David and Thorburn and Henry Jenkins, 1-16.Cambridge: MIT Press. |