"The questions that preoccupy me in the light of recent global violence is, Who counts as human? Whose lives count as lives? And, finally, What makes for a grievable life?"

—Judith Butler

Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (Verso, 2006)

"The one as the other. At one and the same time, but in the same time that is out of joint. The one forgets to remember itself to its self. It keeps and erases the archive of this injustice that it is, of this violence that it does. The one makes itself violence, it violates and does violence to itself. It becomes what it is, the very violence that it does to itself. The determination of the self as one is violence."

—Jacques Derrida

Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (University of Chicago Press, 1998)

“What a useless son you’ve got, Amma; can’t you see there’s a hole in the middle of me the size of a melon?”

—Salman Rushdie

Midnight’s Children (Jonathan Cape, 1981)

Rushdie's (W)Hole - Midnight's Children

A very recently minted doctor, in a new town, is struggling to get his fledgling practice established. He is eventually summoned to the home of a wealthy man who informs the doctor that his daughter is ill. The young doctor enters the ailing daughter’s bedroom and is confronted with the site of two brawny women holding aloft a bed sheet into the center of which a hole has been cut, a seven inch absence of fabric. Behind the opening, the disrobed body of the young woman awaits the anxious doctor’s visual exam. Strictly speaking, of course, a small piece of her body is offered.

The young physician finds himself paged time and time again to the same home to remedy the same young woman for a plethora of alleged ailments and, by virtue of the same hole, finds himself slowly getting to know all aspects of the increasingly desired object(s). He quickly becomes utterly smitten. That is, it is precisely by virtue of the replete absence of the young woman that the young doctor becomes complete; slowly and with but one gaze at a time, the hole fills a desire in him, a lack. The hole, that is, makes a whole.

[One of the earliest forms of the word fascinate (from Latin fascinatus, pp. of fascinare; bewitch, enchant) was used to describe those of unearthly power, specifically witches and serpents; these could render those within the confines of their gaze incapable of movement, unable (unwilling?) to resist.]

Stained Glass

The early Christian churches deployed various successful and original representational techniques to instruct their flocks, one of the most important being the art of mosaic. At a certain point in the development of the mosaic way of arranging space, it was discovered that raking the stones and glass downwards (at a 30° angle, as in the monastery of St. Catherine in the 6th century) would deflect the light earthward toward the viewer in a much more dramatic and persuasive fashion.

Imagining the effect such sites as the early Christian mosaics must have made on the believer is quite nearly impossible; at that point, of course, their subjects were not yet over-inundated with end- and mind-less, ubiquitous images and representations, as is the case in contemporary culture. Imagine her or him walking through what can only have been a magical sphere, the walls and ceiling aglow, the architecture absolutely pulsing and morphing, one wondrous step at a time: an increasingly spellbound, fascinated subject.

And as the space played out its well-orchestrated effects on the consumer of such a divine spectacle, the subject itself likely was similarly changed/reconstructed. As lived space endlessly rearranged itself, the spatial metamorphosis must have had an equally profound effect on the viewer in the process of becoming subject(ed). Viewing the sacred representations-- spaces of the other-worldly, the holy, the “what-is-not-I”-- positioned the subject in a space between the ordinary, adamant and ordinarily adamant earth and a sphere of temporarily attainable otherness and flawless beauty.

Losing one’s self, the process of emptying out. Only to be once again, however temporarily, rendered satiated and saturated with the will of the what-is-not-I.

A Certain Angle

I imagine visitors to the galleries at the exhibition under consideration here and the reinforcing of their self-identities in the spaces. I imagine them wandering through the exhibition and viewing access holes, one might say, cut from an entirely different order of fabric. Spaces of hatred and loathing, vile sites of intolerance. Oneness as violence.

And space will fill a void. It always has.

I consider the mechanisms by which subject-construction takes place now and perhaps during an awestruck exploration of cathedrals in the medieval period as well, if one may extrapolate the machinations and effects of former control spaces based on those of the present. The pedestrian is positioned in a type of triangulation, where one external point alone is inadequate for positioning in space, and, inasmuch as the subject itself is a function of space and its images/objects, so too is one point insufficient in the formulation of subjectivity. Thus: X and Y.

Axis X: a certain distance from a given point. The length of the X axis changes as the subject navigates around and through the exhibition, toward and away from the given representations. The same is the case, of course, for axis Y. In such a way, the construction of self is figured through this triangulation of spatial coordinates, from two axial (dis)placements; one point, again, simply does not suffice.

And this is operational – perhaps must be operational – in the temporal dimension as well. The repeated house calls by Rushdie’s doctor reveal the X: different views, glimpses of his patient. And the patient, in turn, impacts the doctor, which can be described by Y: the doctor’s growing infatuation with the daughter. In this regard, the two coordinates function on a temporal plane. And, as the viewer moves through a cathedral or exhibition venue, the space impacts the pedestrian’s subjectivity and allows for a more precise understanding of the subject’s coordinates. That is, the X and Y coordinates function on a spatial plane and position the subject in a triangulated formation with two other points of Otherness. It is never a matter of the Other, but always a matter of the Others.

Moreover, for any object, peoples, spaces, subjects, for which the observer cannot view the object in its entirety, the observer is forced to make multiple triangulations and undergo multiple metamorphoses of subjectivity as the observer moves around the space or learns more about the object under examination. This could be for an object partially obscured, for cloistered spaces, or things too large to view fully all at once. The triangulated visitors to this show will have the desire to possess, to master the objects and images around them, and their demand will be realized by positioning themselves in the web of triangulations established in the exhibition spaces. It is never that I am not that; it is always and forever a matter of I am not those.

Again, a single instance of alterity never suffices. The Narcissism of Minor Differences will hopefully have created the network, the web of refusals, that create the conditions for the self-positing and hence self-acceptance.

Why refusals and why self-acceptance?

The Case of Philip Guston

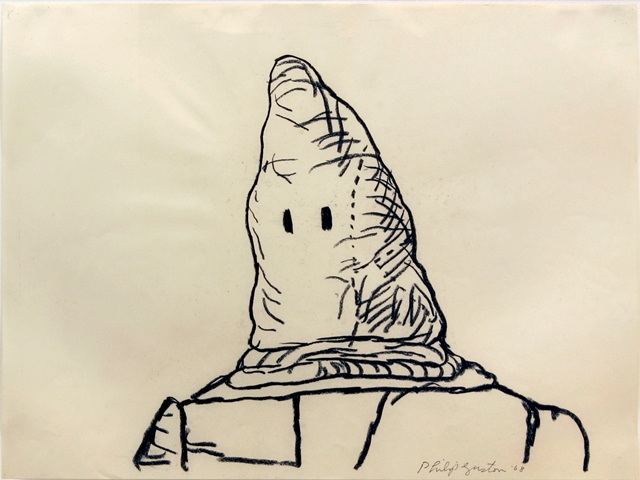

The Exhibition The Narcissism of Minor Similarities (named after a phrase by Freud) took flight from a quotidian conversation about Phillip Guston’s ‘Klu Klux Klan’ paintings (fig. 1). It very much seems to me that Guston’s profound work takes self-criticism to an entirely new and entirely devastating level. There is a war going on outside the walls of Guston’s studio, a bitterly divisive war about race. And Guston remains in the comfort of his loft making paintings. Merely making art.

| figure 1 |

|

Philip Guston

title unknown, 1968

McKee Gallery, New York, New York |

Guston is not an activist, nor is he a racist. His double-negative subject position is created by virtue of being neither this nor that. Thus, he is self-positioned as an artist working away in his studio while cities burn, and, apparently, painfully aware of the fact. If one’s chosen vocation is ill-equipped to provide the lightness of solutions, it is, perhaps, better equipped to provide the dire gravity and burden of their problems.

My fear is that the exhibition will have been a profoundly successful failure, something along the lines of a Guston work. For what does work of this kind and exhibitions of this ilk accomplish other than to reinforce the liberal-democratic, autonomous self?

Imagine a viewer making his or her way through the exhibitions spaces, here confronted by a racist sentiment, there face-to-face with a homophobic one. The viewer refuses: I am not those. And as the voyage through the space continues, she or he confronts more, always more, as the systems of triangulated location bend and assume new configurations. Yet, (unless the spaces are visited by the truly hateful) none will identify with such manifestations of intolerance, or will only do so in the negative. Again: I am not these. The end result of such denial is a consequent acceptance and valorization of the self as currently lived. While outside, the State of Exception persists and the cities continue literally and figuratively to burn.

*

the text accompanied the exhibition The Narcissism of Minor Differences (9 December 2010 - 13 March 2011) co-curated by Gerald Ross and Christopher Whittey at MICA (Maryland Institute College of Art) in Baltimore, Maryland |