Clarissa Tossin

How does it travel? (29 May - 18 July 2015)

Samuel Freeman

2639 South La Cienega Boulevard.

Los Angeles, California 90034

There is no working-class laborer present in the failed modern utopias depicted in Clarissa Tossin’s exhibition How does it travel? (29 May - 18 July 2015) at Samuel Freeman, Los Angeles. Instead, Tossin examines the modernist perspectives of Oscar Niemeyer and Henry Ford using transposition, aerial mapping and imitation to inspect the lingering ramifications of their differing politics. Her use of multiple perspectives frames various iterations of a modernist gaze and functions as a tool for nuanced critique of capitalist alienation.1 Tossin does not attempt to represent the worker but rather aestheticizes the remnants of the worker’s labor to trace the residual effects of Ford and Niemeyer’s utopian visions. In the worker’s place, we find the material residue of their labor as Tossin portrays their toil as a replaceable component of commodity production through transposition, mapping and by inserting herself in place of the laborer. The perception that labor is endlessly interchangeable is a legacy of modernist industrialism and the focus of Tossin’s exhibition.

| figure 1 |

|

When two places look alike, 2013

image courtesy of Samuel Freeman Gallery |

In the photo series When two places look alike, 2013, (fig. 1) Tossin overlays images of homes from two Ford Motor Company towns in Belterra, Brazil (also known as Fordlandia) and Alberta, Michigan. Tossin’s series transposes these two locations as she uses her hand to align a photo of a partial home in one location with the façade of another visited in person. The uncanny likeness of the houses’ architecture and décor makes Ford’s vision of a culturally and architecturally uniform utopia eerily apparent. Distance is compressed and acutely articulates a modernist attitude towards the interchangeability of place and labor by literally transposing one site atop the other.

Within this landscape, the Brazilian Ford workers, whose dwellings Tossin traces, are oddly missing from the picture; their bodies are nowhere to be seen. Instead, our attention is drawn to a rubber replica of a VW Brasília on the gallery floor, a latex copy of the same VW Tossin exhibited in Made in L.A., 2014. The rubber VW, titled Transplanted (VW Brasília), 2012, (fig. 2) is a life-size shell transformed into an ornamental rug. While Transplanted (VW Brasília) is the hide of a machine, it is also the shell of a human prosthetic. The hide suggests the conflation of machine and human and posits the human as equally animal; it is a testament to the industrial era’s vision of working-class labor as a form of expendable and replaceable mechanized production.

| figure 2 |

|

Transplanted (VW Brasília), 2012

image courtesy of Samuel Freeman Gallery

|

As it’s flattened and flayed position suggests, Transplanted (VW Brasília) symbolizes the demise of the automobile but also the exploitation of Brasília’s maintenance laborer, who would likely be driving the car.2 It is the Brazilian laborer that has traveled to Los Angeles, whose toil has subsequently been sprawled out on the gallery floor. Tossin’s rubber VW hide proposes that the maintenance laborer has become nothing more than a fixture, an ornamental object in spaces run and occupied by the wealthy. Here, the gallery symbolizes a site of privilege, drawing parallels between the inexpensive labor of the Brazilian maintenance worker and the Mexican immigrant laboring for unethically low wages in Los Angeles’ art market. Yet the parallels between past and present exploited labor seem inadvertent and uncritical; the exhibition provides no explicit connection between these forms of labor beyond the context of the gallery’s location in Los Angeles.

| figure 3 |

|

|

|

Brasilia by Foot, 2013

images courtesy of Samuel Freeman Gallery |

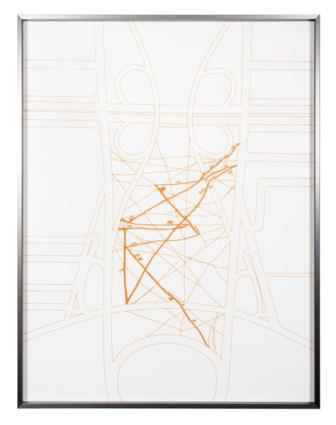

Tossin does, however, use her subject position as an artist to engage different iterations of the Brazilian worker, and, in doing so, centrally figures questions regarding visibility and class at large. In Brasilia by Foot, 2013, (fig. 3) a print series that includes aerial print maps and photos, the artist walked the pedestrian generated footpaths imprinted on Brasília’s Monumental Axis, the city’s central avenue. Oscar Niemeyer designed the avenue with the vehicle in mind and failed to include pedestrian friendly walkways. Tossin thus used her body to count the distance traversed by those before her—those likely unable to travel the city by car—highlighting everyday forms of resistance to the built environment.3 The resulting prints are aerial maps depicting the outline of the architectural landscape as well as the footpaths walked by Tossin. Here, the artist is a stand-in for the number of pedestrians that have walked before her and will continue to walk these paths post her documentation. Yet she simultaneously functions as the architect, in this case Niemeyer, using aerial imaging techniques to document her path. As the only visible body in this exhibition, Tossin doubles as the Brazilian worker and as the architect. The conflation of her artistic labor with that of her subjects places Tossin in a precarious relationship to her subjects, creating a consistent tension throughout the show. In using her body and privileged artistic labor as a substitute for the worker, Tossin obscures the plight of the Brazilian industrial and maintenance laborers, risking further alienation of the worker in order to explore the modernist ideologies of Niemeyer and Ford.

It is here that the “it” from the title of the exhibition, How does it travel?, comes powerfully into play. The “it” is a floating target in which the human is not privileged but reduced in favor of eliciting a Marxist critique on commodity fetishism.4 Tossin aestheticizes the commodity fetish and, in doing so, visually traces a process of alienation within Brazilian capitalist societies while implicating global capitalist markets. There is a sense of restricted mobility that pervades the show despite its international content. In the photo series When two places look alike, the artist focus on the homes of Ford’s workers, suggesting a form of stasis. The conflation of place using collage conjures a form of child’s play that suggests a form of mobility not yet obtained. Similar themes of mobility/immobility are apparent in Brasilia by Foot as Tossin maps the pedestrian footpaths from an aerial perspective, a point of view often associated with flight. Tossin may travel across borders to create her work, but the viewer gets the sense that such travel is not as easy for her working class subjects.

| figure 4 |

|

Brasília, Cars, Pools and Other Modernities, 2013

image courtesy of Samuel Freeman Gallery |

As I exited Samuel Freeman gallery, I found myself face-to-face with the actual VW Brasília vehicle that was used as a mold for the rubber car shell inside. The piece, titled Brasília, Cars, Pools and Other Modernities, 2013, (fig. 4) was stuffed with pool cleaning gear and seemed out of place on the affluent street.5 I had somehow managed to overlook the vehicle upon entering the gallery despite its deliberate placement blocking Samuel Freeman’s front entrance. I couldn’t help but feel that my oversight was tied to the show’s overarching modernist perspective regarding the perceived expendability of working-class labor. Tossin’s exhibition leaves the viewer to linger somewhere between the modernist pursuits she highlights and the esoteric material culture occupied and owned by the worker. The show is not about making the laborer visible, but, rather, replicates the modernist point of view, leaving the viewer to wonder where the worker has gone.

1 I use the term “modernist gaze” in a broad sense to reference a post World War I industrial turn that influenced popular thought, favoring human kind’s ability to create and reshape the built environment through science, technology and art. This time period produced those, like Oscar Niemeyer, who sought to create environments for the masses, and those like Henry Ford who saw the potential in harnessing the labor power of the masses.

2 As Sally Frater notes in her article Traversing Geographies, Collapsing Architectures that the VW Brasília was an affordable vehicle used by laborers who were working general maintenance and repair jobs for wealthy individuals (http://x-traonline.org/article/traversing-geographies/).

3 Brasília became Brazil’s capital city in 1960. The city’s urban planning and architecture, developed by Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa, was designed as a socialist utopia, as a city for the masses in which people of all classes lived and worked side by side. Niemeyer designed Brasília’s central avenue, Monumental Axis, with this vision in mind. Tossin’s work, Brasília by Foot, highlights one manner in which Niemeyer’s architectural design’s failed to live up to the socialist utopia he had envisioned.

4 Karl Marx’s commodity fetish asserts that the exchange value of the commodity in the market conceals the human relations involved in the production of the product, obscuring the exploitation of the laborers used to make the commodity.

5 In Brasília, Cars, Pools and Other Modernities there is a single channel video documentation ofthe artist driving the VW from Brasília to Niemeyer’s Strick House in Santa Monica, Los Angeles. She is seen stepping out of the car with pool cleaning gear in hand as if she is going to clean the pool at the residence. The piece was commissioned by Artspace San Antonio and featured the video as well as the vehicle in the gallery space.

|