Let me set the scene for you:

I am usually assigned one of the last seating groups to board the airplane because I like to leave my seating preference to the planets. I shove my bag under my feet because there is no more room above and try to settle in with something to read. I always acknowledge my fellow passengers because my Midwestern parents taught me good manners and grace. This inevitably leads to this conversation,

“You traveling home?”

“Yes—to Detroit.”

“To DetroitDetroit?”

“Ahh. Yes. Are you asking if I live in Detroit proper? I have lived there—in SW Detroit by the Ambassador Bridge for nine years.”

“Oh, I hear Detroit is really making a comeback these days.”

“....Hmm, well I think it really depends on who you are talking to…”

“Oh really? What with Dan Gilbert and the new stadiums and everything. And all the artists moving there?”

“Well yeah...it’s great for people like me. I am an artist in fact. I have been able to have my studio there and do some really great projects and live affordably. But I am the target demographic for this development you are hearing about—a well educated, white woman with some skills. Detroit is great for people like me. It has been a good city to me. I try to love it back.”

“See isn’t that wonderful. How much do you sell your art for…”

“But it isn’t like that for many Detroiters who are living, working and doing their thing to get by in the many neighborhoods all over the city. There is a lot of unemployment, disenfranchisement, lack of resources to the things you and I take for granted—the ability to jump in our cars and go where we need to and to open up our laptops and get online...it’s pretty crazy. Two realities of Detroit exist.”

“...Oh.”

“But Detroiters are incredibly creative and persistent. A new kind of city is happening…”

“...Ah...”

By this point in the conversation, I have made this person uncomfortable or just disinterested. The same old media paradigm, “Failing city saved by God-like CEO”, has shifted and s/he doesn’t care to hear anymore. Development in Detroitis complex and layered, and can be very uncomfortable when words like gentrification, racism and classism become part of the conversation. As a white artist living in this majority-black city for the last nine years, these are issues that I continue to confront on a daily basis. And as more artists continue to relocate to this city, I think it is imperative that it becomes part of the development conversation.

Detroit’s arts community needs an advocate at the city level when big development decisions are being made and when potential opportunities arise. Artists1 see opportunity where others may not. Artists collaborate and commune in unique ways with the land, the neighborhood, community members and history. Artists notice things that others may not. Art makes Detroit the great city it has always been with deep layers, character, and soul and it will only continue to produce this kind of culture if we support it.

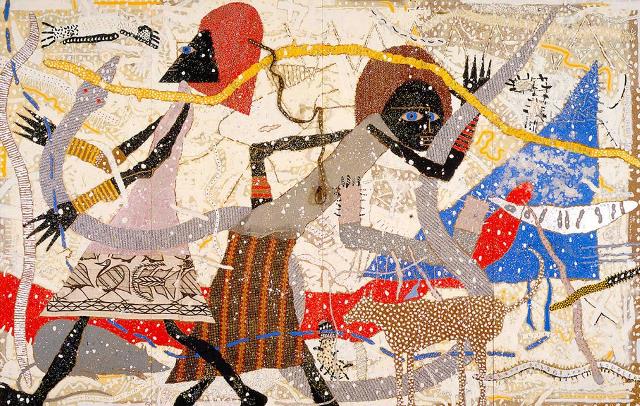

| figure 1 |

|

Charles McGee, Noah’s Ark: Genesis, Enamel and mixed media on masonite, 1984. In the collection at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Born in Detroit in 1924, Charles McGee has worked tirelessly as an advocate and educator towards arts for all of Detroit’s children. |

When Theaster Gates was here speaking during the Ideas City Conference in Detroit on April 30th about his work in Chicago, he had a very poetic way of putting it. He compared the role of the artist in the city to that of a large family. He talked about how the disciplinary siblings—the sister of architecture, the sister of urban planning, the sister of communications and others within the city infrastructure often become siloed. They stop doing what families should do. They don’t talk to one another; they don’t communicate. But when you place an artist in the mix, these disciplinary siblings begin to reconnect. Often, the artist becomes the thread that weaves them back together again, so they open up conversations and begin to see new possibilities. Artists do not work in strict disciplines with firm lines drawn between them. They can think holistically about a place, a particular challenge or something that may seem at first like a deficit.

When applied practically at the municipal level, buildings that were once slated for demolition can become community art spaces like Mr. Gates’ project titled, “Stony Island Arts Bank” (2012) or his Dorcester Projects, 2009, both situated on Chicago’s South Side. As Mr. Gates talked during the panel discussion, he was flanked by Michelle T. Boone, the Commissioner of the City of Chicago’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, who was very proud of the work Theaster had done in her city. But she also took credit for her assistance, at the governmental level, for helping to push his projects through when there were naysayers or for helping to translate his ideas for those who couldn’t quite grasp his vision.

Detroit needs our own Michelle T. Boone—speaking on behalf of artists, projects and organizations who are doing great work in this city.

| figure 2 |

|

| Chazz Miller - artist, muralist, and owner of Public Art Workz who has helped to transform parts of Old Redford, NE Detroit, and Brightmor through his work |

Detroit’s last Department of Cultural Affairs was established in 1995 during Mayor Dennis Archer’s tenure (from 1993 - 2001). The Department came about as part of an election battle between the candidates Dennis Archer and Sharon McPhail around Detroit cultural resurgence; establishing the Department became one of Archer’s campaign promises. He is quoted as saying, “Detroit, to be a great city again, must recognize the importance of the arts, our cultural institutions and programs."2

Mayor Archer was good on his promise, although a few years into his job, but nonetheless had Marilyn Wheaton, the former director of Concerned Citizens for the Arts3, directing the Department. Although Ms. Wheaton didn’t have a budget to dole out to artists4, what she did do was create important collaborations and great opportunities for the arts and civic entities to engage in real ways. One most notable to me was her engagement with under-represented groups during the 2000 Census.5 Wheaton worked with specific artists to create outdoor murals in their neighborhoods so that they could draw folks out of their homes to participate in making an artwork, as well as in the Census. She wanted to make it a less threatening, invasive experience for the mostly non-English speaking, immigrant groups who felt that the Census experience was often wrought and challenging. Not only did the City get more accurate population results, they also graced their neighborhood walls with three new murals in distinct and thriving communities. Marilyn’s work with the Census and the murals is a shining example of Theaster’s weaving together of disparate disciplines. Had she not been a listening ear at a conversation about the challenges in these particular neighborhoods, these murals wouldn’t have happened. She knew about the artistic talent that existed at the ground level in the city and was able to create opportunity for everyone.

| figure 3 |

|

| The Alley Project (TAP) in SW Detroit - a predominantly Latino community. A gathering space has been created where youth can gather to create art from graffiti, to visual art, music, poetry, etc. |

Unfortunately, for the City of Detroit, for our citizens and our community of artists, the Department of Cultural Affairs was dissolved in 2005 during Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick’s administration (2002 - 2008). Ms. Wheaton was not reappointed to the Department and—because her fundraising talents were lost—so was the Department’s financial backbone and with it, all the programming. Ms. Wheaton came into an administration with a strong support for public art and left with an administration whose agenda shifted. With these challenges inherent in elected administrative bodies, I asked Wheaton about the importance of government’s role in the arts. She says:

Some elected officials—all of whom are ordinary people—will incorporate arts and culture into their portfolio so to speak, others will not. Some elected officials come into office with a breadth of understanding about the value of the arts. Others may never understand the importance of the arts to their city or community. Because of that disparity among elected officials, I believe it's up to individuals who care deeply about their community to advocate for a healthy city department that focuses on individual artists and their needs, as well as the organizations that produce and support those artists. A healthy and vibrant cultural environment is as important to human beings as clean water, sound infrastructure, good schools, building codes, public transportation, etc.

Wheaton is calling on all of us—from artists, to institutions, to corporations, to government—to take up the charge of supporting the arts in our city. Many of us feel deeply as she does that a vibrant culture is elemental to our well-being as many of the other services rendered at the municipal level. But given the tenuous status of services like education, safety, and infrastructure in the City of Detroit, where does culture fit in? With an administration that is constantly shifting through an election cycle; with a city that is just reeling from bankruptcy and getting back on its feet; with many new developments moving fast and furiously from Quicken Loans, to the Red Wings, to the housing along the riverfront, to the newest thing in “Midtown”; where does an Arts and Culture Advocate belong amidst all of the noise?

I feel that we can make the case that the arts can offer up solutions and relief from the noise that can often overwhelm municipalities. Artists derive solutions often where others see none. A condemned building can become a beautiful gathering site where community workshops can be hosted, but we need clearance from Buildings, Safety and Engineering (BSE) to help make this happen. Musicians can gather at the site of a neighborhood tragedy to raise funds for a family, a church or a small business to help them rebuild. But we need assistance from the police department to close down the street for the day and host a festival. Rather than tearing down a local homeless shelter, local designers and architects can gather to redesign the interior to bring in more light, space, safety and private space. However, these design professionals need to know that this challenge exists and that their expertise is necessary. These are anecdotal ways that creative thinkers can engage in a city like Detroit that is in transition, unable to commit to a tried and true department. Practitioners in the arts need to be a part of the new Detroit that is happening and mechanism thru which to engage.

| figure 4 |

|

| Documentation of The Sidewalk Festival that takes place in Old Redford in The Artist Village - one of the spaces that was created by Chazz Miller. Dancer and creative organizer/activist Ryan Myers-Johnson created the event in 2012 to bring art out of the institutions and into the streets. |

In speaking with Sheila Cockrel, former Detroit City Councilwoman (1994 - 2009) about the reinstatement of a Department of Cultural Affairs, she says, “The City needs fewer Departments, not more...but I think in this era of resurgence there would be an openness to support some sort of arts liaison or facilitator." Ms. Cockrel was serving Detroit during Archer’s administration and worked alongside Marilyn Wheaton. She believes in the value of arts and artists for the health and longevity of a city. However, she also witnessed the challenges of art in a bureaucratic setting. There were times when bringing art into the governmental sphere could stymie its path forward.

Since the Department of Cultural Affairs was eliminated in 2005, numerous efforts have been launched by multiple individuals and groups to reinstate an arts representative at the city level. I have been part of a few of these efforts prior to the bankruptcy. In speaking with Marilyn Wheaton, Sheila Cockrel, artists, design professionals, musicians and performers, I heard other rumblings of concurrent conversations happening at different levels with non-profit and educational leaders, and beyond.

I want to take this opportunity to address the creative community at large. How do we come together on this issue and present a united front to the City of Detroit? What sort of advocacy structure could successfully include the concerns of artists both newly arrived and native Detroiters? How do we take better charge of an equitable development that includes the arts in a meaningful way? I know conversations have begun out there in many spheres. Let’s bring the ideas together and see what can happen.

If you are interested in continuing this conversation. Please contact the author at: megheeres@gmail.com

footnotes

1 I am using the term artists in the broadest way possible to include all culture creators from visual artists, musicians, dancers, architects, designers, chefs, carpenters, and makers of all kinds.

2 Gabriel, Larry, “ Arts groups struggle with new strategies for making ends meet.” Detroit Free Press. 5H. 9 Oct. 1994: Print.

3 Stevens, Ruth. “Young artists to gather for Michigan Youth Arts Festival.” https://www.wmich.edu/wmu/news/1998/9804/9798-282.html. Web. April 28, 1998.

4 Staff writers. “Art for the future.” Detroit Metro Times. Arts & Culture. June 24, 1998. Print.

5 N.p. “Creative Partnerships and Unexpected, Non-Traditional Methods Mark Mayor Archer’s City of Detroit Campaign to Count Everyone During Census 2000.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1rY_Uztrv7rYpZ5n2X9fPx9BRan-rwILxqAIqxKyVMNU/edit. Web. March 20, 2000.

|