| figure 1 |

|

Dirt in the foreground. Mercury Cougar in the background. Orange., 1971

image courtesy DIA Samuel Wagstaff papers archive

|

PREAMBLE: ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES

A photograph (fig. 1). 1971. Dirt in the foreground. Mercury Cougar in the background. Orange. Could be a soft top. Vinyl top. We don’t know. Richard does a google image search. The closest match we find is the craigslist find of the day: a ’67 Mercury Cougar. Google also finds an ad – a two-page spread – for the 1970 Mercury Cougar. A blonde woman’s head sits on the split between the two pages. She holds a cougar by a chain leash. A live cougar, that is.

But we digress …

This is an essay in six parts. Each part serves as a container for possibilities: about Detroit-as-place; about the stories that are told here and told about here; about an art work that – in 1971 – was attempted here; and about another art work that – in 2014 – may or may not have anything to do with here.

Richard began the essay. He said: these are my crude notes. That’s something that people say: crude notes. It’s a way of being humble about what you’ve done – call it crude. But in this case, crude stood out to me as more than a simple gesture of humility. Because the word references vulgarity. Doesn’t it? Crude, rude and socially backwards, my mom would say. And here we were, starting an essay with a photograph of dirt. Dirty dirt. Michael Heizer’s dirt. Or – Detroit’s dirt that Michael Heizer dug up. And the perceptions of vulgarity that surrounded that act of digging up.

I wondered what else crude was designed to reference. I wondered if crude as a word could help us get at the inexplicable, visceral nature of our reception of Heizer’s Dragged Mass, 1971, (fig. 2) and its relationship to Detroit as place. I wondered if now, almost forty-three years after Dragged Mass was made and subsequently erased, crude was the only way to describe our efforts at reaching back into a moment in time that we did not live, that we were not here for: a moment viewed from the obscenity of distance.

Nice to discover “approximate” as the fourth definition down for crude. An opening. An alternative. Approximate as that which is near or adjacent to but not quite the thing, itself. Yes. That satisfies my need to articulate the partial, digressive nature of this text. A series of departures. Always departing from the present moment in a forward trajectory, even as we continually hurtle ourselves backward in time, revisiting those haunted points of yesterday: before, prior, last minute. Arriving always nowhere. Because we can’t sit still in this moment and we can’t let go of the moment just elapsed. I find these temporal dilemmas to be somehow akin to what Laurie Anderson talks about in Walking and Falling, 1982:

You're walking. And you don't always realize it,

but you're always falling.

With each step you fall forward slightly.

And then catch yourself from falling.

Over and over, you're falling.

And then catching yourself from falling.

And this is how you can be walking and falling

at the same time.

We arrive at these approximations by departing from various points of origin: two photographs, two newspaper articles, a few song lyrics … another photograph. And memories. Lots of memories. We are walking our memories forward. And we are falling backwards through time and space in order to get there. We gesture at so many points of arrival. And we find ourselves cast adrift in a sea of departures.

Richard has written some things down. I have written on top, beside, underneath, in between. Sometimes we use italics or brackets or parentheses or little-sized font to demarcate the dialogic nature of the text. Sometimes the dialogue is invisible.

Perhaps you will be able to hear it.

Tipping my imaginary hat to Bertolt Brecht, I will list the titles of all six sections before we proceed: a way of telling you where we are headed before we begin the journey, a way of voiding some of the conventional theatrical power our stories might hold – lest we get ahead of ourselves and feign certainty, perform authority. A way of reinforcing the materiality of our intentions, amidst the necessary chaos in our delivery.

1. Introduction to Our Experience of Detroit

2. Description of Dragged Mass

3. What We Want Dragged Mass to Be

4. Questioning Our Desire to Use Dragged Mass’ Seeming Failure and Un-Acceptance to Explain Detroit

5. Desire to Compare Dragged Mass to Matthew Buckingham’s Image of Absalon to be Projected Until it Vanishes

6. Need for Totems/Actions/Experiences to Explain the Unexplainable

So, do we digress? Or, don’t we? Is there such a thing as a digression anyway? Don’t all arrivals begin as departures? The blonde woman and her chain-linked cougar. The living cougar – the animal cougar – as the approximation of the 1970 car cougar. The 1970 cougar as the approximation of the ’67 cougar as the approximation of the image of the parked car in the 1971 photograph of Dragged Mass. The sculpture as the approximation of what the artist intended. The sculpture as the dereliction of art as the board of the DIA imagined it. The sculpture that was subsequently disappeared. In the city with the disappearing population.

1. INTRODUCTION TO OUR EXPERIENCE OF DETROIT

REOCCURRING MYTHS AND LEGENDS

We moved to Detroit in 2009, during the great recession. [Was it great? Are we just calling it that in this article or do other people call it that now? I could look it up on google but I’m exhausted with looking up answers to questions like these on google. Let’s just leave it here: the great recession. That’s what we’re calling it. That’s how we’re remembering it.]And the auto bailout. [Yes, the auto bailout. That happened.] It seemed that everyone we met here had a story to tell that pointed to this place’s past: a present reality that was the result of a past action, indiscretion. We heard many stories. There was one about members of the UAW being paid 90 dollars an hour to sweep an empty assembly plant. [Who told us that one? I don’t remember. Or – I don’t remember who. I do remember that the story was told.] Another one was about being Bob Seeger’s manager in the late 70’s. [Was that the real estate agent who showed us the foreclosed house of the puppeteer who had died? Kitchen tiles decorated with little animated Italian chefs. Dancing bowls of spaghetti. A fanciful space for food preparation. Countertop adorned with a pile of mail accumulated from the previous owner. Among the envelopes: a bill from an office specializing in weight loss surgery.] Someone else told us they had booked the Bob Seeger System to play their high school prom. And more than a few said that downtown Detroit was a thriving Bohemian village in the 1980’s.

Where were we?

Being a non-native Detroiter, this place is fodder for my imagination to run wild: investing in its myths and legends. The city’s white panther party and its slogan of dope, guns and fucking in the streets reached me in my teenage years in Sacramento, CA. This place’s storied history is full of political, cultural, and criminal polar extremes: landscapes of profound blight paired with blocks of turn-of-the-century architectural marvels; suburbs filled with the worst-of-the-most-banal suburban track homes interspersed with pristine Victorian enclaves; outrageous mayoral scandals and infamous city council corruption; an empty light-rail train that runs laps on a tiny course in the vacant downtown while everybody else waits hours to get anywhere useful via bus. Rough rusty beaters barreling down Woodward in blizzard conditions and shiny stinky metal classics coughing and constipating the same concrete artery during the Dream Cruise in August. This tumultuous groundwork – composed of seemingly endless collisions between contradictions – is bound to continually produce new truths. Or – new notions of truth? Unstable ground giving way to great gaping holes at our feet, shifting plates giving rise to … fresh soil underneath.

And that brings us to one of the most interesting stories told to us – one that, upon hearing, seemed to explain this place in all of its obscure particularity: the story of Dragged Mass by Michael Heizer.

| figure 2 |

|

Michael Heizer

Dragged Mass, 1971

earth displaced by literally dragging a massive thirty-ton block of stone over the ground

Detroit Institute of Arts

image courtesy DIA Samuel Wagstaff papers archive

|

2. DESCRIPTION OF DRAGGED MASS

Sharp-dressed lady poses in front of the failed artwork. Matching top and skirt. Or is it just a single dress? Boots. Purse. Eyeglasses. Necklace. Hair. What a broad, my dad would say. And he would mean it in a good way. She smiles a thin smile at the photographer, who captures granite block and the giant metal cables in her midst. The metal cables, drawn over the granite like claws – a monumental eagle’s talons. The metal cables, curling and snaking in a corner on the right, as if a head might pop out from the mound of dirt and bite the little lady in the orange dress. Or is it rust-colored? She clutches her purse.

In 1971, Detroit Institute of the Arts curator Samuel Wagstaff mounted a show by artist Michael Heizer titled Actual Size. Included among his photographic and sculptural works was a plan for a long-term outdoor installation titled Dragged Mass. It consisted of a 35-ton slab of granite, which was dragged across the lawn of the DIA by heavy moving equipment. The project was purposely designed to create a gouge across the campus of the DIA, with the slab being left at its final dragged location, thereby creating a narrative of process. The creation of the piece did not go as planned. This resulted in a work that was not as clear and decisive as Heizer initially conceived.

Julian Myers writes: Even with the help of two D8 Caterpillar tractors and a ten-man crew, and despite the fact the Institute had replaced the lawn with loose dirt two days before, the block refused to sink into the earth. Instead, it slid awkwardly across the prepared surface. “It didn’t tilt, burrow, or dig into the ground, and it didn’t sculpt,” wrote a reporter from the Detroit Free Press; a frustrated Heizer was quoted as saying “We screwed up.” The mound of dirt that was supposed to accumulate as the rock was dragged along also failed to materialize, forcing Heizer to shove it into place with two extra bulldozers. The earth mound we see in photographs of the work is not the material result of the stone’s drag, but a simulation of the “impressive pile” the artist had imagined. (Myers, Julian. "Mirror-Travel in the Motor City." X-TRA Contemporary Art Quarterly. 2014. http://x-traonline.org/article/mirror-travel-in-the-motor-city/)

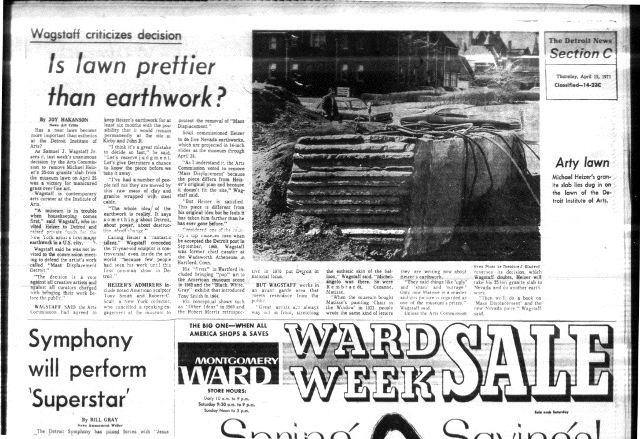

Immediately, the work elicited polarized reactions from viewers. Some questioned its merit as art. Many publicly called for its removal. After several weeks of debate, fueled by news reports and editorials (fig. 3), the DIA Arts Commission weighed in on the matter. They called for the removal of Dragged Mass, to the dismay of Wagstaff, Heizer, and arts professionals nationwide.

| figure 3 |

|

| image courtesy Detroit Free Press Microfilm archive, April 1971 |

3. WHAT WE WANT DRAGGED MASS TO BE

In our imagined version of the work, there is an absolute beauty to Heizer’s labor that plays and plays and replays in our heads. [Like little children who stare in awe at backhoes and bulldozers working in the roadway. Like little children who wait at the window for the garbage men to come. Something about the sound and feel – and the smell, even – of great, lumbering machines at work.]In our imagined version of the work, there is a poignant, punctuated aftermath, an aftermath tempered by a silence: the silence of the gouge left behind, the silence of the jagged brown scar against the tailored green landscape of the DIA. But this silence never happened. Instead: a mess of news reportage. Instead: a mangled manicure to the DIA’s lawn.

The work didn’t have an aftermath in real time: no silence, no awe. A future that never was. A state of perpetual failure, retold endlessly.

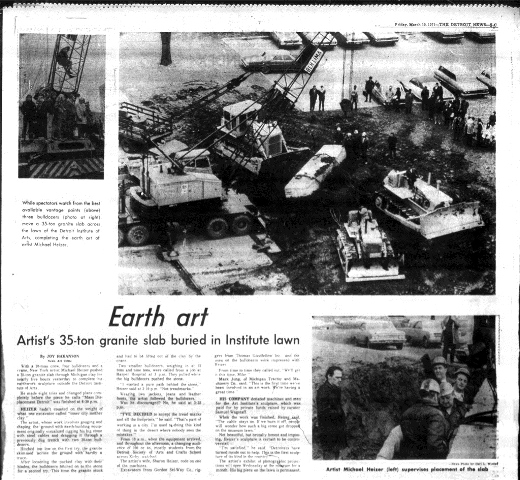

In the recesses of my mind, I make a false memory of the work. I think of a brief pause in the speed of the world. Like the silence immediately after a car wreck, a fatal catastrophe. I combine that with another conjured, fictitious memory of seeing Heizer’s gouges out in the Nevada desert. And now I can hear the deafening silence of the scar across the museum’s grounds (fig. 4). It is rather beautiful. It is un-representable: a non-thing, formless. A voiceless void in a boomtown that has been the victim of endless chatter.

| figure 4 |

|

| image courtesy Detroit Free Press Microfilm archive, April 1971 |

4. QUESTIONING OUR DESIRE TO USE DRAGGED MASS’ SEEMING FAILURE AND UN-ACCEPTANCE TO EXPLAIN DETROIT

It has been weeks now since we said we wanted to write about this work, and from the time we were first inflicted with its story [infected with this story?] we’ve been going back and forth about how it might be emblematic of Detroit. How might it be.

Dragged Mass’ presence and absence. It’s presence in its absence. The absence in its presence. Two mirrored surfaces reflecting each other, commenting on each other, plunging sight lines into infinity. Opening up a visual chasm of what exists created out of what doesn’t exist. Funny mirrors looking at each other, producing a vision of what is here out of the immateriality of reflective surfaces, reflective structures.

Although it would seem that Detroit, post-1967, has been framed as aftermath-in-perpetuity, we arrive at an oppositional conclusion: Detroit has never had an aftermath. Or – no proper aftermath. No pause. No silence. No true reverence. Only: Will it ever escape its past? A future that never was? A region littered with the refuse of supposed-to-be, on the way to becoming. All this juxtaposed against the current incarnation of Detroit necrophilia. How to bring a corpse back to life? Or – is it not a corpse but rather Mrs. Havisham in her dress with her cake and her cobwebs and her longing?

Upon continued reflection we think … Why do we want to posit that the Dragged Mass story is an answer for this place?

[Call and Response: Is Detroit is unexplainable? (silence)]

[What is this impulse?]

5. DESIRE TO COMPARE DRAGGED MASS TO MATTHEW BUCKINGHAM’S IMAGE of ABSALON to be PROJECTED UNTIL it VANISHES: NOT JUST A DETROIT PHENOMENON?

Then one day we are in Ann Arbor. Ann Arbor. What a different place. All that wealth and privilege. Or so it seems.

Until you visit on an afternoon during winter break and in the

absence of all those student bodies, the atmosphere is rather stark. A German family in the museum. Two dozen chaperoned adolescents wearing blue shirts that say: HAIL. Cigarettes. Homeless men gathered in an indentation between two buildings. Extra large soda containers. A vigorous conversation led by a man whose face shows how long he’s been sleeping rough. But his black jeans are brand spanking new. Oversized for his thin frame. Never been washed. Christmas was three days ago. Must certainly be a gift from the shelter or social services or … Never mind. Just make sure the stroller is traveling a safe distance from all that breath and spit and grime where the sidewalk meets the shop window.

And so we are here. But we are also so many other places. So many other elsewheres.

We think we find an answer in Matthew Buckingham’s IMAGE OF ABSALON TO BE PROJECTED UNTIL IT VANISHES, 2001, (fig. 5) on view at the University of Michigan Art Museum. The work is as its title states: an image on a slide of a statue of the Danish historical figure Absalon, continually projected by way of a conventional slide projector until it vanishes. The heat and light of the machine gradually, steadily drains the image of its color, ultimately leaving more and more of a holograph, until nothing but projected white light remains. On the wall next to the disappearing image, in a simple black frame, Matthew Buckingham has included a brief narrative about Absalon the man, and his role in the creation of the place now known as Copenhagen. Several centuries of turmoil – some brought on by Absalon, himself, and some brought on by the memory of Absalon. Or – controversies over how and if he should be remembered.

As we walk closer and closer to the place on the wall where the projector sheds its light, tracing our fingertips over the now-translucent outlines which are the remains of the image, it is amusing and unsettling how the framed narrative takes on increasing importance.

Richard takes a few clandestine photographs. Because: No Photographs, a small sign says on the podium upon which the projector is placed.

Look around. Three, maybe four men in security guard blazers. Just over there. But they are distracted by the wedding party taking their own photos on the other side of the room.

6. NEED FOR TOTEMS/ACTIONS/EXPERIENCES TO EXPLAIN THE UNEXPLAINABLE

Don’t believe in yourself. Don’t deceive with belief. Knowledge comes with death’s release.

Ah …

Ah …

-David Bowie, “Quicksand” |

Infinity is known. It can be explained to us as a phenomenon, illustrated for us iconographically. We can’t truly comprehend it. But we’ve created a little symbol to stand in for this unknown.

So is Detroit an unknown. We can be in it. Certainly. Sure. Our bodies can exist in a space called Detroit. We can even go so far as to account for its history with words on a page, framed and hung on the wall next to a disappearing image. But these words, these shapes, these conversations with a wall – these are not answers. They are calls. Calls. Phone calls in the dark. Before phones were illuminated. When you could really make a call in the pitch black dark.

Our need to make Dragged Mass a compass of Detroit comes from a desire to make the formidable unknown apprehensible. We need a stand-in, a totem, a miniature. We sift through time and find something resembling insight from Claude Levi-Strauss. In The Savage Mind, Levi-Strauss, speaking to the value of man-made objects modeled after things occurring in the world writes, “the intrinsic value of a small scale model is that it compensates for the renunciation of sensible dimensions by the acquisition of intelligible dimensions.” A little thing. A little thing to stand in for the big thing. The great unknown. The dark questions that haunt and inspire. And the intelligible existing in the dialogue between the homologue of the thing (Levi-Strauss) and the questions we ask that will never be answered.

We don’t have time for knowledge to come with death’s release. We take refuge in the reduction of the unknown onto a bodily scale. Levi-Strauss, again: “this quantitative transposition extends and diversifies our power over a homologue of the thing, and by means of it the latter can be grasped, assessed and apprehended at a glance.”

These impulses: to photograph Detroit’s ruins, or experience them through urban spelunking, to take issue with and slander the population that takes those photos and makes those journeys into the ruins, to research failed Michael Heizer sculptures, to urban-farm in a region surrounded by farmland, to Lift Detroit in Prayer on a bumper sticker, to try to leverage “art” out your eastern market/mid-town boutique, to … to … to … is in a sense an act of sculpture, a making of your own miniature copy of 100 years of accumulation of countless unfathomable occurrences as a means to bring an intelligible dimension to what happens between your first and last breath. |