Ed Fraga: Tabula Rasa

25 October-29 November 2014

Re:View Gallery

444 W Willis Street

Detroit, Michigan 48201

http://www.reviewcontemporary.com/tabula-rasa/

figure 1 |

|

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632

oil on canvas

216.5 cm × 169.5 cm (85.2 in × 66.7 in)

Mauritshuis, The Hague

|

†There is a sensation of being watched upon entering the opening of Ed Fraga’s latest show, Tabula Rasa. Walking through the door of gallery #1, a table rests in the middle of the room with a crowd of onlookers keeping to its perimeter, not quite observing but also not neglecting. This table, which looks both rustic and spare, is a work in and of itself, constructed from a freezer door. Walking through the room, the pieces calling the most immediate attention contain a famous image of Rembrandt’s Dr. Tulp (fig. 1), 1632, in which a cadaver is dissected and displayed by a lead doctor before a diligent group. In this instance, the observers depicted in the original painting have been removed and a veil of diffused plastic obscures the image, leaving only the white corpse of an executed prisoner.

The image of the cadaver was repeated again on another piece: a plastic curtain hanging from a dowel-rod with grey paint escaping from the pasted image down to a mock bonfire, already turned to char. People congregated in the various corners of the room nervously before continuing to gallery #2. Painted a warm brown, the next room is cast with spotlights, striking several colorful paintings and free of objects. A gallerist-turned-bartender asks if viewers want wine; people stand around with cups extended, adding to the intensely warm environment. Amongst this room’s inviting canvases, the question is posed through absence of the initial Tulp: what is the the artist’s intention with such imagery and how does it figure into the entirety of the show?

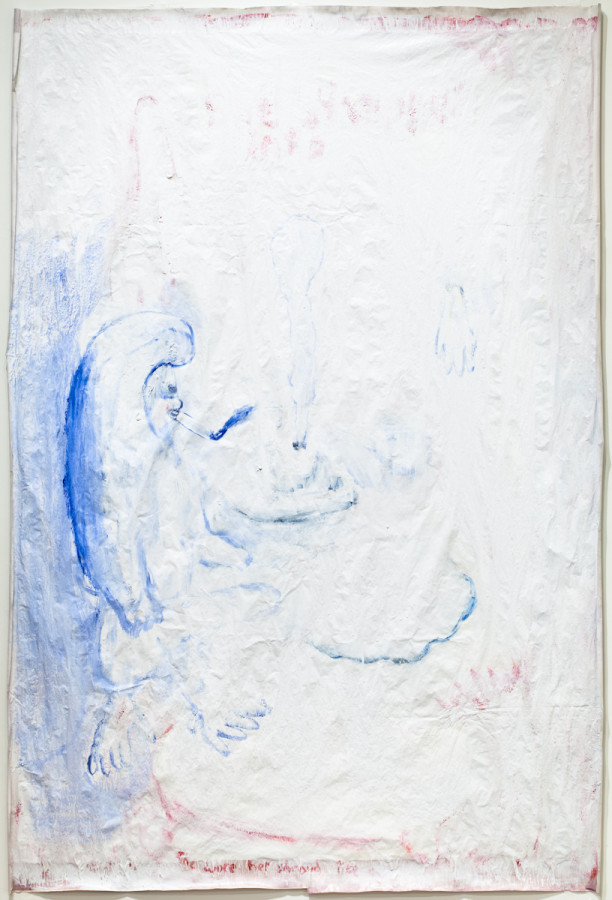

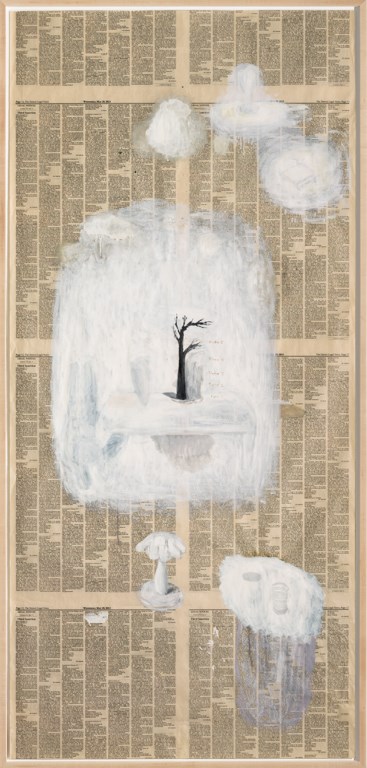

At Re:View Gallery, Fraga’s canvases and sculptures offer a variety of images, some made readily available and others obscured. Through ambiguity, the mind is given a chance to dwell on the possibility of what is withheld from sight as works cause viewers to consider a dark fantasy of dismemberment (amongst other horrific experiences) happening while forcibly locked inside the whiteness of erasure, revealed only briefly through a rorschach of mangled brush strokes. Certain paintings in the show speak more than others, such as Queen Bee (fig. 2), 2014, and Gretta’s News (fig. 3), 2014. Whereas others are hampered in a cloud of conceptual experimentation and curatorial side-steps, these two works are so powerful that they blow past any attempt to rationalize or understand.

figure 2 |

|

Ed Fraga

Queen Bee, 2014

Oil, latex on glassine

72 x 50 inches (framed)

image courtesy Re:View

|

figure 3 |

|

Ed Fraga

Gretta's news, 2014

Gesso, oil on newspaper

69 x 33 inches

image courtesy Re:View

|

One is still left to wonder, why would a painter who has the ability to depict anything choose to wheat-paste images on various pieces inside the show? A Rembrandt is quite hard to render in oil paint, especially at a small size, but it would have been recognized regardless of execution through its repetition in the show. Similarly, there is another image pasted inside of Eternal Fire, 2014. Undoubtedly purposeful in this instance, this action cannot be removed from its reminiscent quality of a freshman intro-to-painting class, wherein an ungrounded concept is met with a dearth in skill. Similarly, what is the reasoning for one of the pieces, Table/Procession, 2014, being placed so high on the wall, where viewers cannot look closely upon it, or the smudge of coal along one of the wall plinths? These moments give the impression of quick aesthetic decisions without prolonged investigation of the viewers experience in the gallery.

Table/Procession depicts the reference of a dining room table, an image from James Joyce’s The Dead (Grant Richards Ltd., London, 1914). A viewer can vaguely identify the image, but is nevertheless left with discouragement from a lack of consideration with its inclusion of the gallery’s need to sell work. This issue becomes acutely noticeable in confronting this, the third piece upon entry into the gallery, as a tiny number (3) against a blank wall relays from 4 feet below the piece that hangs above viewers’ heads. One may look up at a beautifully framed thing, and then look back down to eye level at the tiny number, and up again, and down again and again. The necessity to make clear a work’s price under lackluster curation/preparation replaces the artist’s intentions for the works’ experience (assuming they are even present), itself obscured by the oddity of a demarcation that divides artists from collectors.

Artists chide Re:View Gallery from time to time. One friend commented when asked if he knew of the gallery, ‘You mean the one connected to the design store?’ Personally, I have always wanted to have a shower-party opening at Re:View where everyone comes to the art-show’s opening in bathrobes and takes full advantage of the public shower installed in its bathroom. Admittedly, the moment of entering Tabula Rasa, a viewer confronts a price-list, which immediately identifies the most important piece in the show, that is, the most expensive one, eponymously titled Tabula Rasa (priced at $20,000 dollars). Despite the price tags, in considering all of the galleries within Detroit and those that line its suburbs which legitimately call attention to art, few sell work periodically.

Some hypothesize that in order to have a thriving art scene a region needs five basic pillars: artists, galleries, schools, criticism and collectors. While Re:View might sacrifice the immediate experience certain works could offer viewers, it does so with the intent of courting local collectors. Though doubtful that the greater body of Detroit artists will begin selling works to such collectors, the process can likely nurture a broader dialogue and indirectly bolster artists’ practices.

In that vein, even if there is a sacrifice at times (one of the pieces was hung over a kitchen sink in the second gallery, where the glare of a spot-light made the work impossible to view), the gallery is still giving artists the freedom to put shows together however they see fit. Additionally, Re:View has the confidence to put a high price-tag on works whose values are not immediately telling. In this way, it is expanding the possibility of value in art amongst it’s patrons.

In this instance then, what is the tabula rasa of Tabula Rasa? Considering the objects and images employed (the artist father’s dismembered ladder, a portrait of his late mother as a balloon, or even of his own blood entombed in the wax tablet), the artist’s sincerity is put on display as erased white cadavers, plopped about before the objectifying students, wine drinking socialites who dine around, timid to prod at a subject matter that is soulful yet uncomfortable. At it’s best, what Ed Fraga’s paintings deliver is an undeniable truth of the human psyche that dwells within everyone, waiting to be unearthed through years of incremental self-discovery and experience. When successful, they have the ability to conjure up an aura of unknowability, as if an explosion has awoken a body from slumber, but the noise is no longer present for the mind to examine. To consider the analogy of Fraga’s paintings to dreams, their role outside of the artists studio is to deliver images of anxiety and in doing so, viewers are given an experience that safeguards them from the pitfalls of day-to-day life. It is this anxiety that forms the foundation of the works aura. Though they may cringe at the sight of it, examining the dead prisoner allows the group to learn about what they themselves are made of.

There is something to be said within Fraga’s work for breaking down the previously assembled, and, as a badge, the gallery shows it with pride: through destruction one may reach new and undiscovered heights of psychological and emotional understanding. No wonder, then, to hear that the artist recently lost a loved one to whom some works can be attributed. The rage of a red body, murdering another in an armed robbery, an ensnared prisoner executed, is turned white and picked apart to reveal the emotions, frustrations, and failures that brought him to his demise. Perhaps, in such a way, the use of the material in Gretta’s News, a discarded paper reel listing foreclosed homes (a material inherited from the artists dear friend and fellow Detroit artist, the late Mary Ann Aitken) is transformed into another work, from the frustration of a lost friend, forcibly reborn, bearing the image of a bed, a cup, a vase with flowers, a dead tree, and all of these coming together to form over the original surface, the face of a smiling caricature; and smiling at fellow art-goers, avoiding any talk or heavy conversation, viewers exit the white gallery opening with a price list and a shattered plastic wine cup, purged! |