There is an artwork, unarguably a political statement, yet one that resists all that is political. This object takes a position yet stands against the fixity of positions. A monument that serves as a fuck-you to all that is monumental, and to those who erect gross reflections of their own power.

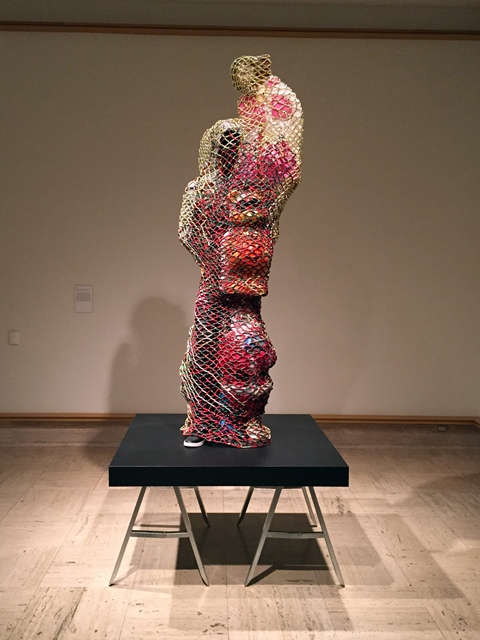

TM 13, 2015, (fig. 1) is a sculpture by Nick Cave, referencing the slain African American teenager Trayvon Martin1. A black mannequin wearing black denim pants, black shoes and a hooded camouflaged sweatshirt, is surrounded by lawn ornaments—a Santa Claus, a bear holding a jack o’ lantern, a gnome, a Jesus and an angel. A net of beads and pipe cleaners stretches over the objects, binding them together. All these objects stand upon a thin riser placed tenuously on two cheap, folding aluminum-sawhorses.

| figure 1 |

|

Nick Cave

TM 13, 2015

mannequin, hooded sweatshirt, denim jeans, sneakers, blow molds, pony beads, pipe cleaners, and metal sawhorses.

photo courtesy Anthony Marcellini |

The materials of TM 13 are not precious; they are fairly common factory-made items—cast plastic and stamped out aluminum—found in big box stores and garages. The mannequin is mass-produced and almost faceless, not representational of an individual but of a multitude, any black man, boy or anyone’s son. The model is also the structure beneath many of Cave’s soundsuits —his well-known performative sculptures—when they are exhibited or left at rest. This plastic body is surrounded, almost overcome, by Kitsch: the ubiquitous, tacky and very American plastic lawn ornaments found on front yards of American homes. Representations of the American desire for fantasy and escape, of our desire for simulation and stimulation, the seemingly infinite production of plastic and saccharine, and ultimately as a representation of the security of property.

In its hooded withdrawal, the black figure seems to hide from or, at least, resist the presence of these representations of uniformity and prepackaged individuality. The net that binds them is constructed from arts and crafts materials, beads and pipe cleaners, unassuming objects preschoolers use to make bracelets or simple sculptures, reminders that, when he was shot, Trayvon Martin was holding a bag of Skittles candies and a watermelon flavored drink—a seventeen year old with the stature of a man and the desires of a child.

From the shopping-mall mannequin, to the front lawn ornaments, to the beads and pipe-cleaners bought in bulk at crafts stores, to the sawhorses of DIY home improvement, the materials of TM 13 radiate suburbia, the mixture of the rampant ease of capitalism and one-stop shopping with paranoia and xenophobia and its manifestations of gated communities and private security.

TM 13 is a strange and moving work, a mixture of contradictions; it stands at a complete disregard to everything outside it. Its aesthetics suggest temporality, like a march or a protest, setup quickly to occupy a public space, to agitate and unsettle, then just as quickly folded up and removed. It is made from materials considered cheap yet durable, plastics with an almost unlimited shelf life, which will take hundreds of years to breakdown, maybe outlasting bronze.

The mannequin seems to recoil from the objects surrounding it, trapped by the beaded net like Laocoön and His Sons against the serpents. Yet the net also serves as a comfort when we realize each bead was carefully strung onto the pipe cleaners, one by one, by attentive human hands. We find these same materials covering many of Cave’s other soundsuits. He initially created the soundsuit in response to the 1991 Rodney King beating as a way to disguise an individual’s race, sex and identity, and to create a public noise maker—visually and audibly—against the constraints of society. Together the net and the lawn ornaments, create a kind of Soundsuit for the ghost of Trayvon Martin. A way for a dead black teenager to make an outcry and an uproar, to protest against his undeserved demise.

Finally, and strongest of all, what TM 13 imparts is distance and detachment from its human audience. Ultimately, the combination of forms and their seemingly competing associations are so strange that the object stands alien and unfamiliar. It is not a didactic work, it does not lecture or preach. In fact it does not care about you. Understanding is your job. It is your job to approach the artwork, to recognize it. It is a subject that stands apart, that refuses to respond to the hail of authority, to the profiling of “hey you there”, and, thus, remains completely an object2.

TM 13 is an objective thing, an object whose intentions and actions are vibrant yet unknown. It communicates in another language, and resists answering to any definition. It is independent and at a remove from everything else: a monument to the ungraspable. Death, injustice, and stupidity, are as unyielding as resistance, love and abstraction.

The Artwork as Agent

Inanimate objects, such as TM13, seem to appear animate because they affect us and instigate events. In this way, we apprehend them more like beings, entities or spirits, things that perform. An object’s definition is shaped through its interaction with other things. In this sense, we might think of an artwork as a kind of social agent.

Alfred Gell, in his anthropological theory of art, Art and Agency (Oxford University Press, 1998), defines an agent as persons and things “who/which are seen as initiating causal sequences of a particular type, that is events caused by acts of mind or will or intention, rather than the mere concatenation of physical events.”3 This is to say that agents are things that directly cause actions and reactions. They are social agents in that they are actors in social relations. This is not to say that artworks are exactly living: they are not sentient beings; they do not have intentions of their own outside of human intentions placed upon them. Rather, artworks elicit reactions and responses based on other objects’ social interactions with them. And because they sometimes perform in unexpected ways, they are often surprising. Agents are uncertain objects.

In Art and Agency, Gell also describes art as an act of transformation, “No Matter what avant-garde school of art one considers, it is always the case that materials, and the ideas associated with those materials are taken up and transformed into something else, even if it is only, as in the case of Duchamp’s notorious urinal, by putting them in an art exhibition and providing them with a title (Fountain) and an author (‘R. Mutt’ alias M. Duchamp, 1917).”4 Shift or changeability is at the core of the art experience, it is, what Gell later describes as, “the essential alchemy of art, which is to make what is not, out of what is, and to make what is, out of what is not.”5 Yet I would further this by suggesting, if transformation is a visible component of the artwork, it also retains or suggests the memory of its prior state. And in the case of some artworks, they never completely transform from one thing into another but are both simultaneously the pre- and post-transformed: urinal and fountain, mannequin and Trayvon.

An artist or the museum creates a situation that asks the audience to imagine an object they may be very familiar with, as something other than it is. Partially, this transformation may happen because the museum, gallery or art context, which designates it as art, gives the object the ability to float freely from the restraints we place upon objects in other situations, such as in the case of tools or functional items. And sometimes we experience objects that we have simply never encountered before and thus have no prior experience to understand them.

In addition, art also shifts and changes over time based on its new social interactions. It is capable, like all things, of transformation, but its prior forms and exchanges have left marks and paper trails. It wears the scars of its transformations, exchanges and provenance. Even an object that carries no scars is still changed by events or circumstances. A painting hung in Adolf Hitler’s office is not the same afterwards as it was prior to this event. This ability to change, to be affected by its experiences, is what distinguishes it.

Destructive Plasticity

But what does it mean to really transform? How does one thing become not just another but a completely different other? A complete transformation would be one in which not simply the form, but also the nature or essence of the object changes as well. The form cannot be thought separate from essence; both are connected and affected by the transformation. In Catherine Malabou’s Ontology of the Accident (Polity, 2012), she describes the problem with Kafka’s story, “The Metamorphosis” lies in the fact that the protagonist Gregor, who turns into a cockroach, is still able to narrate his transformation to us, when, in fact, had he fully transformed into a cockroach, he would be unable to communicate in human language—or perhaps, would completely lose the desire to communicate.6

For Malabou, a true mutation is as follows: “We must find a way to think a mutation that engages both form and being, a new form that is literally a form of being…the fabrication of a new person, a novel form of life, without anything in common with a preceding form.”7 This description of a transformation or a metamorphosis is what she refers to throughout the book as ‘destructive plasticity’—not simply a gradual forming or sculpting of the body, but a notion that humans are plastic, pliable and develop through our experiences. Destructive plasticity is a change that completely alters the original, in substance, personality and intentions; it is a shift of form to the marrow, a shift that leaves traces of the object's former state yet renders it alien to what it was prior.

Most of the examples of destructive plasticity Malabou describes are caused by traumatic moments, such as the aftereffects of war, like post-traumatic stress syndrome or the trauma of a disease that alters brain chemistry, like dementia or Alzheimer’s. But does destructive plasticity have to be this violent or extreme? In some ways, you could also think of less tragic life experiences as a type of minor destructive plasticity: learning how to swim; the euphoria of eating food from different cultures; the first time watching Fugazi play; visiting the Rothko retrospective at the National Gallery in 1998; being treated as an outsider while living in other countries; reading Judith Butler, bell hooks, Herbert Marcuse or Graham Harman; having a child. After each one of these experiences, I was completely changed and my former self most certainly felt like a stranger.

And destructive plasticity can also extend to things. Objects are changed by their experiences as much as people. They become mutated things, opposite to their former selves.

The Exploded Thinker

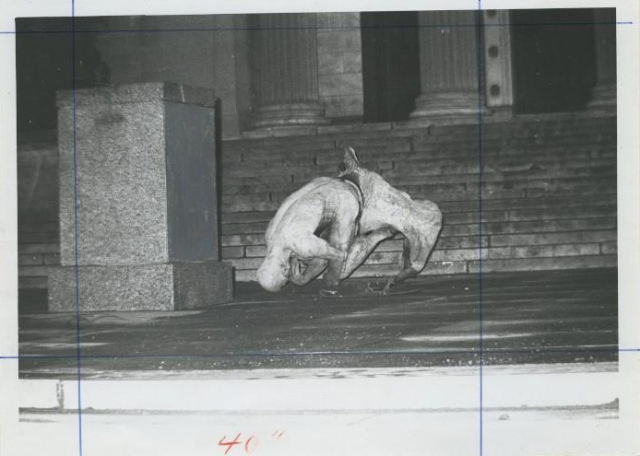

| figure 2 |

|

Auguste Rodin’s

The Thinker, 1980 - 1981

image taken of the statue after being blown off its base on 24 March 1970

photo by C.D. Moore. |

There is a sculpture in front of the Cleveland Museum of Art that wears the scars of a traumatic event, an event that completely transformed the sculpture, both physically and conceptually. On March 24, 1970, dynamite was placed between the legs of a life-size, almost ubiquitous bronze sculpture, The Thinker (1904) by Rodin, and then detonated (fig. 2). The explosion knocked it off of its pedestal and severely transformed the lower half, destroying the base and melting the lower part of the sculpture’s legs upwards. Investigators suspected the explosion was caused by a cell of the leftist “terrorist” group the Weathermen. Yet there was no clear motive and the Weathermen never claimed responsibility, no arrests were made. Following the event, due to both the technical difficulties, the costs and extent of the restoration—which would have essentially resulted in a total recasting of The Thinker—the museum instead chose to embrace the event and decided not to restore the sculpture but preserve it in its exploded form8.

This new ‘exploded’ Thinker (fig. 3) now sits, or rather floats atop its base, as if permanently stuck mid explosion, the melted metal pushed up and out by the force, creating the appearance of a pensive genie floating on a tattered magic rug. This transformed Thinker is a new thing, a total stranger to its former self. It no longer represents the ideas of the original. Nor could we even say it is any more a work of Rodin but rather some kind of hijacked collaboration between Rodin, the bombmaker and the dynamite itself. The result is chiseled by the event. “Destruction has its own sculpting tools.”9 Thickening the muddle of a sculpture already once severed from its context; originally The Thinker was titled The Poet, meant to represent Dante and the strength of his creativity and vision, intended to be positioned above Rodin’s Gates of Hell, bronze gates referencing Dante’s The Divine Comedy (1320), for a never finished Decorative Arts Museum. Now the fire from an unforeseen hell reflects on the poet.

| figure 3 |

|

Auguste Rodin,

The Thinker, 1880-1881

bronze, green patina; 182.9 x 98.4 x 142.2 cm

gift of Ralph King 1917 to the Cleveland Museum of Art

remounted in front of the museum in 1974

photo by Krist Jake |

This ‘exploded’ Thinker is a completely new object, completely transformed by the volatile event. It still carries traits from its prior life. We recognize that it was once The Thinker, yet the event had such a transformative experience on the object that it is equally representative of the cause; we recognize it was changed by an explosion. This ‘exploded’ Thinker is part The Thinker, part dynamite driven explosion and part social statement by the museum to accept the event as a creative act10, with an entirely new symbolic reading, one never intended by Rodin, and perhaps not even by the perpetrators. It is a declaration of sorts that nothing is immutable, even those things fixed and solid, cast metal or, for that matter, the seeming solidity of a 100-year-old bronze sculpture. Both the ‘exploded’ Thinker and TM 13 represent the outcome of violent acts, yet also decisions to continue on, to recognize what occurred in a statement of perseverance.

1 The title of the work are the initials of Trayvon Martin's name and the year, 2013, that the private security guard George Zimmerman, who killed him, was acquitted of Martin’s murder.

2 Marxist philosopher Louis Althusser describes the process at which individuals become subjects in society as ‘Hailing’ or ‘interpellation’. This process occurs when a person is addressed by some authority figure, such as the police, in a public place. When the individual turns around, accepting their address, they are transformed into a subject. “Assuming that the theoretical scene I have imagined takes place in the street, the hailed individual will turn round. By this mere one-hundred-and-eighty-degree physical conversion, he becomes a subject. Why? Because he has recognized that the hail was ‘really’ addressed to him, and that ‘it was really him who was hailed’” Louis Althusser, "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses (Notes towards an Investigation)", in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (New York City: Monthly Review Press, 1971)

3 Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1998): p. 16

4 Catherine Malabou, Otology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009): p. 53

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.: pp. 17-18

7 Ibid.

8 The decision to not repair the sculpture is best summed up by the following statement from the director of the Cleveland Art Museum, Sherman Lee, “we do not wish the sculpture to be repaired since the extent of damage requires such extensive repair and replacement that we believe that it would be no better than a modern cast comparable to those issued by the Rodin Museum.” In Bruce Christman, “Twenty-Five Years After The Bomb: Maintaining Cleveland's The Thinker” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation (1998, Volume 37, Number 2, Article 2) 173 to 186, JAIC Online, http://cool.conservation-us.org/jaic/articles/jaic37-02-002.html

9 Catherine Malabou, Otology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009): p. 4

10 The decision to leave the The Thinker in its damaged state was also influenced in part by comments on Rodin’s practice made by a Rodin scholar Albert Olsen: “Rodin was the first sculptor in history to take seriously the partial figure as a complete work of art and to accept, court and even welcome chance and accident in the making or subsequent history of his sculptures…He did accept studio accidents that resulted in the battering, breaking and discoloring of works over a long period of time…In Rodin's view, his sculptures were so well made, so beautifully formed and expressive throughout, that, like classical fragments, parts of his work could hold up as being complete in themselves. Even in its present, ruined state, your Thinker is still an impressive sculpture and supports Rodin's view. Only Rodin's work by its history and the way it was made can withstand such a tragedy, with any degree of dignity.”

See Bruce Christman, “Twenty-Five Years After The Bomb: Maintaining Cleveland's The Thinker” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation (1998, Volume 37, Number 2, Article 2): pp. 173 to 186, JAIC Online, http://cool.conservation-us.org/jaic/articles/jaic37-02-002.html

|