On Friday, February 23, 2007, my wife Tannisha and I visited Gilda Snowden’s third floor studio at 2000 Brooklyn in downtown Detroit, Michigan. Gilda wore a green Cass Tech Alumni sweatshirt and I recorded our interview on an old, portable cassette tape player.

Gilda Snowden--artist, writer, curator, professor and lifelong Detroiter--was one of the city’s greatest artistic talents. She was an alumnus of Cass Technical High School and Wayne State University, where she received a Bachelor of Fine Arts, Master of Art and Master of Fine Arts in Painting. She served as a Professor and acted briefly as Interim Department Chair of Fine Arts at the College for Creative Studies (Detroit) and Gallery Director of the Detroit Repertory Theatre. Gilda was a foremost artist of Detroit’s Cass Corridor art and cultural scene of the 1970’s and 80’s. While educating and mentoring a countless number of artists, including myself, Gilda believed that an ever-expanding and radical studio practice is required for forward progression as an artist. Her art was robust, energetic and visually striking. Her humanity and passion for art inspired the entire arts community in Detroit for almost 40 years.

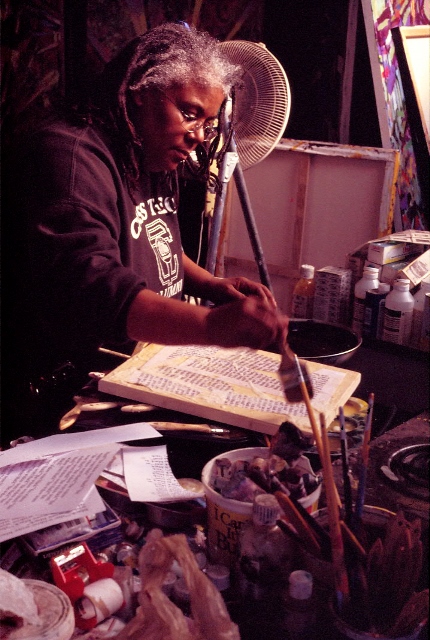

| figure 1 |

|

| Gilda Snowden in her studio |

Visiting Gilda’s studio was always a very intimidating yet exhilarating experience. From the very moment of entry, one would be immediately engulfed by the enormity of her creative ferocity, made manifest by the sheer volume of work. There were drawings, paintings, sculpture, sketchbooks, books and art materials covering every available surface; on the floor, in boxes, on shelves, on the walls. Navigating her studio terrain was humbling. It reminded me of just how much work I wasn’t doing in my own studio and it made me keenly aware that my hopes of ever “catching up” to her production schedule were most assuredly in vain. She represented the pinnacle of what a true artist is and should be, sacrificing every conceivable space in the room for the production of art and the release of creative energy.

My mother, artist Shirley Woodson, first took me to see Gilda’s work and studio in the mid-1980’s when she worked out of a fifth floor loft in the heart of downtown Detroit on East Grand River, just above Spectacles clothing store. In this space, Gilda had a long, white wall where she would neatly order multiple sheets of paper that hung side by side. The sheets hung just high enough to capture a projection of her silhouette as it appeared on the paper. I watched, entranced, as she manipulated her long locs into knots, up-dos, braids and many other creative, abstract forms to create different shapes for the self-portrait silhouettes.

She arranged her surfaces in such a way that allowed her to draw, paint, drip, splatter and melt pigment across each paper simultaneously, capturing the full breadth of each mark-making session. This ensured that a multitude of visual ideas would be captured and contained in their own space. Gilda was very strategic and actively avoided piling too many ideas on one surface. She carefully allowed for each visual notation and color scheme to have their own composition, yielding highly cohesive bodies of work that were like families of visual iterations for that given time period. This methodology enabled her to maintain a diversity of images, while allowing ample room for success and failure. It also gave her an opportunity to make many works in large volume simultaneously. Her process was liberating, beautifully messy and brilliantly efficient.

At the time of this interview with Gilda on Brooklyn Street, she was still creating multiples concurrently. She had a small setup in her studio for creating encaustic work, complete with several pots of wax and pigment. There were hot plates, wax bricks and stacks of wooden panels in a variety of sizes ready to be deployed for making art. In fact, right after our interview, Gilda demonstrated her encaustic process for us. Using old Pentax and Canon AE1 film cameras, Tannisha and I took photographs as Gilda used newspaper clippings and unpigmented beeswax to create a few ground surfaces on 11” x 14” wooden panels. Our visit lasted about two hours, as Gilda was preparing for an art supply run. I left that day anxious to get back home to my own artistic process and inspired to do everything I could to keep up with my teacher and mentor.

Gilda Snowden and my mother were the best of friends, having exhibited and worked together as members of the National Conference of Artists Michigan Chapter, an arts organization dedicated to the preservation, promotion and support of African American culture through African American visual arts. After my mother, Gilda has been my foremost inspiration as an artist. I have been studying the work of Gilda Snowden throughout my entire life, taking notes and learning lessons about what it means to be an artist and, more specifically, a painter. Being able to grow up analyzing the work of an amazing visual artist was a form of schooling in and of itself that continues to inform me as an artist.

Just weeks after her eagerly awaited sixtieth birthday, Gilda passed away suddenly on September 9, 2014.

The following is an excerpt from our conversation in 2007.

Senghor Reid: Okay. My first question: I want to ask you about the tornado series.

Gilda Snowden: Oh good, it’s been a while since I worked on those.

| figure 2 |

|

| Gilda Snowden in her studio |

SR: What was the tornado series about?

GS: Well, many levels. It was an excuse for me to paint abstractly, but still using an object or a visual focus. It was a reference for my autobiography in the sense that I always had dreams and nightmares about the occurrence of tornadoes, but, most importantly, it was a signature image for me; [it was] mine [in] that [it] would allow me to just forget about subject matter and get me into painting. I haven’t done any for a while, but just because you haven’t worked on a subject for a while, it doesn’t mean you can’t go back to it. Every artist reserves the right to review what they’ve done in the past, they could go back to it… they could do whatever they want. So, for example, right now I’m painting small, encaustic pictures of flowers, but that doesn’t preclude me from tomorrow doing tornadoes.

I used to worry about the whole notion of being known for one thing or another, and not being able, and I used to worry about that. And I remember when I participated in a show in 1990 at the [Detroit Institute of Arts] and I had pastels and large sculptures, paintings [from] another series that was tangential, called ‘Self and Storm and the Tornado’. When it was hung one of the curators said, “well now you can move on to something else,” as if that indicated the end of the series and I felt really odd. I didn’t know how to tell that person “no.” I mean this doesn’t signify any kind of conclusion. This is just a show.

And if you had to change your style, like if a style had to be accomplished every year, that’s... not paying attention to what your inner drive is and what you want to do. So, I like to think of the tornadoes. In fact, I’ve been doing some small drawings in a little Moleskine that I keep in my purse or stuff in my office drawer and, when I think about it, I doodle tornadoes. So, it hasn’t ever left me. So, I’m thinking when will I get back into them? Do I want to do these large pictures again? Do I want to do something small and more intimate? I haven’t thought about that, but I know that I’m going to do them again because they belong to me. And there are a lot of other artists who use them in their work, too and they all do them differently.

SR: Do you feel like you need to do them a certain way? Or do you feel you will need to do those kind of tornado paintings again based on the way you feel the audience might react to them?

GS: No, I do them based on what I want. The audience is going to react however they are going to react. No, I shouldn’t really say that. I do think about the audience, but not when I’m painting. Not when I’m conceiving of them [the paintings]. After they’re done, I wonder, “Well, how are they going to view this?” And especially, if I do a show of tornado paintings and I haven’t done them for a while, people are going to say, ‘Well, where did those come from?’ and ‘Well, is she abandoning her chair paintings? What does this mean? I’m confused!’ And so okay, you’re going to be confused, [because] I’m not confused. I’ll do a chair painting one day and a tornado painting another day and a flower [because] now I just want to do what I want to do. I keep coming back to Picasso who doesn’t do the same thing. I think of Philip Guston who changed overnight. All the artists that I admire are people who have done things outside of the realm of approval, people like Al Loving. You know Al Loving got into trouble early on, you know this? When he stopped doing those…

SR: Septehedrons?

GS: Yeah, you know those shaped paintings, the geometrics ones and then he started tearing up the canvas and the gallery got angry at him. I think they may have sued him.

| figure 3 |

|

| Gilda Snowden in her studio |

SR: Yeah, they did.

GS: And so you have to be willing to face that. Fortunately, I’m not in that position. I don’t want anyone to hold my foot to the fire and say, “You must do this!” or such. I’m fortunate in that. So, I put myself in a position where I don’t have to deal with that.

SR: Why did you initially move away, for a time, from working three-dimensionally?

GS: There’s a couple of reasons for that, too. I began to desire the flat surface because I was brought up as a painter, and, as I was being taught painting and being influenced by my own painting, I was also influenced by Cass Corridor artists who were into three-dimensional construction situations. That’s why I kind of got suddenly into it. Then, I segued away from it because I wanted to do flat things again and use more color, but also, on a practical level, they began to fill up my studio and take up lots of space. In fact, behind that black wall over there are a whole lot of constructions (phone rings) that I wish I could sell. No, don’t stop it.

(Gilda answers her cellphone and her husband, William Boswell, is on the other end)

“Hi Boswell. Hi. I’m in my studio and Senghor and Tannisha are here, and Senghor is interviewing me . . . no come here . . . alright bye.”

That’s okay.

SR: That was pretty cool.

GS: Yeah, uh . . .

(laughter)

Yeah, Boswell is coming and we are going to Dick Blick [to] take advantage of the 70% off sale…

ALL: (big laughter)

GS: …on canvases. But see, canvases are flat; canvases are lightweight. Constructions are big and round and heavy. Not that I don’t do them. I’ll do them as a commission, but I can’t do them on an everyday basis right now because my mind isn’t into it, my heart isn’t into it and also I just,…it's taking up too much space. [When] I moved into this space, it was totally empty and now my working area has shrunk, and what I’m doing when I get out of school is I’m taking a lot of stuff out of here. Then, my working space will be, huge. [Because] I need to make more work all at one time and I’ll do constructions. In fact, I just did one a while ago for [a] commission at Blue Cross. It’s in their lobby and I hadn’t been doing constructions…but they wanted a construction, so I did a construction. It was big. It was twelve feet long and maybe eight feet tall. It’s in their lobby; it’s right in the building off of Lafayette and Beaubien. You can look in the door and see it, and I’ll do that if it’s sold.

So, it’s like, you know how when you’re driving in the country and there are no buildings that obstruct your view of the landscape. The landscape that is right next to you is going [by] real[ly] fast. And then the middle space goes by slower and, in the far distance, it’s very small, it’s like it’s barely moving. I see those three distances as being different bodies of work. The one that’s closest to me goes by really fast; [that’s] all [of] the paintings and drawings that I’m doing now. The one that’s in the middle might be some work that I like to do, but I do it like every ten months. And, then, the stuff in the background, that goes by real slow, but it’s still moving. [These] are things like [the] large scale sculptures or constructions that I might do like every two years. So, I still do them, but it’s at different viewing distances. And, so, I tell people that I’m always considering [different] types of work. [If] I’m thinking about constructions, especially large-scale ones, I’ll do drawings of them or sketches and not even full scale drawings, just so that I have a memory or record of what that could be, so that if a commission comes up I can just jump right into it.

I look at this painting right now (motions to another painting)… it has all these layers that came about because I started using tape to mask off [sections]. [I] did these before I got this job [as Interim Chair of the CCS Fine Arts Department], but I’m just adding more and more and more onto them. And whenever I do something like that in my work I’ll ask myself ‘why am I doing it?’ because I do believe there’s underlying reasons. One of the things I do notice, when I look at any of [those acrylic paintings] back there is that, structurally, they’re very similar to my older tornado paintings. There’s some things that you can leave and there other things that you can’t leave; but the density of them is part and parcel, due to the fact that with acrylic paint you can do all of that. You can layer, it’ll dry. Layer, dry. Layer, dry and so I can put on ten different layers in one painting session. And I’m thinking, ‘maybe you should like hold off,’ which is one of the reasons why I paint on so many pictures at one time, so that I don’t make one picture carry the whole weight. But, now, it’s getting to the point where I have to paint on ten pictures at one time so that I can spread it all out. But I’m letting those paintings, like the one’s on the black wall back there, I’m letting them sit for a while. Now I haven’t worked on them for like, maybe three months, like I’ll look at them because I don’t know what I want to do next. One thing that I do have in the back of my mind is that there’s a deadline coming up very, very soon; February 28th is the deadline for the application for the New American painting competition. Do you know about that? February 28th is the deadline, the postmark deadline. I’m trying to think, I need slides, which pieces am I going to send in? Either those or do I send in my flower paintings or do I send them…what do I send them? Because I enter--I didn’t enter last year--I’m entering this year…so I have to narrow down. I can’t send one of each…that would look scattered.

| figure 4 |

|

| Gilda Snowden in her studio |

SR: Yeah.

GS: Do I feel like I want those paintings to speak for me if I get chosen? I don’t mind…but then, I thought, I do mind. It’s all about making choices and editing and asking yourself questions about what’s important in your work. So, I’m always asking myself that. And you kind of get a sense that my mind right now is just as dense as those paintings because I’m thinking about so many different issues that I’m trying to put them all in at one time.

SR: Do you think that’s a problem? Or is that just…

GS: Sometimes I think it’s a problem because I like clarity; I like succinctness. But, then, other times, I say it’s the way I am right now, so you have to acknowledge where you are and who you are, because that’s who you are. I’m not who I was five years ago. I do know who I’m going to be five years from now. I am who I am right now. Those paintings are reflective of who I am. That’s why I don’t call…they are not the greatest paintings, I don’t call them that. Other people come in, “oh it’s fabulous”, but what they’re responding to is something else…visual bombastity or bright colors. I know what’s wrong with my paintings and I know what I need to do to fix them. Most of the time people come in and they don’t agree with me. They think that I’m putting myself down when I say these are not the best paintings. No, I’m just being truthful. I know what I need to do: I need to work more on them. I can’t do it right now, so I’m just doing a lot of thinking. So in a way, this time off may be good for me because it gives me time to reflect intellectually without a brush in my hand.

SR: What I really like about those paintings is that they have a different kind of depth from what you’d normally get out of one of your larger works. You know you can kinda walk into it and almost sit in the chair.

GS: Well, that’s interesting to hear that because there was a critic that came up here, [Dr.] Roger Green, and he criticized my work. Hi Boswell, can you sit down for a few minutes? […] Roger Green came up here and…a number of years ago he gave a fabulous review when I had a show in Kendall College’s gallery. He saw my show with the paintings of the chairs and the stuff around them; and he thought the stuff around the chairs was redundant; that the chair itself was the focal point and it should be developed. He liked the small chairs at the top there that are with themselves. And I didn’t disagree with him one hundred percent. I also realized he came and it was the first time he saw them, even though he is a critic and looks at a lot of art, it was still his first impression after looking at these paintings. And, so, I didn’t get upset or anything, I just realized you know this is what it’s about. But I didn’t disagree with him, but I wasn’t going to change and stop doing these big paintings because this guy walks in here and says that this stuff is extremist or not focused or what have you. I’d rather say, I’ve made the commitment, now how do I…how do I fix it or make it better for myself? So it becomes an assignment that I give myself and so that’s good. They’re all assignments and, then, if I have a show or put them somewhere and people like them, then that’s okay, but they’re all still assignments.

Every work I do is not “Art” with a capital “A”, it’s something I have to do to express myself. Like when Dickens was writing A Tale of Two Cities he was writing a story, he wasn’t writing “literature.” He was writing a story, it had to go through revision and editing. That’s Dickens. I can’t do that? We all need to do that. I find a lot of my students especially, everything they do is like “this is fabulous”, “this is great” but they’re not; and I’m trying to teach them within the body of work you have […] all the things that lead up to the body of work. All the drawings, sketches, preliminary mistakes, they’re all part of the body of work. The resolved pieces may be not as important to you as all the stuff that led up to it, that’s what you learn. And so, that’s what I’m still reminding myself…that you have to understand the procedures.

| figure 5 |

|

| Gilda Snowden in her studio |

|