“It was hard to tell the new highway from the old road: they were both confounded into a unitary chaos.”

Robert Smithson1

I got in my car and drove Downtown on East Jefferson. At the assortment of sculptures dotting Hart Plaza, I turned right onto Woodward and detoured around Campus Martius, avoiding people in suits hurriedly chasing lunch. Just past Interstate 75, gray peaks presented themselves at the construction site of the future Red Wings arena. Continuing north, I slalomed through the migrating range of mini-mountains created as a result of the M1 Rail line; barriers and piles that serve as arterial clogs in Detroit’s aorta. Each distinctive pile suggested itself as a site, an un-monumental marker. The garish orange barricades designating the constantly shifting roadway accompanied me until East Grand Boulevard, when they suddenly fell off and left me amid gated storefronts.

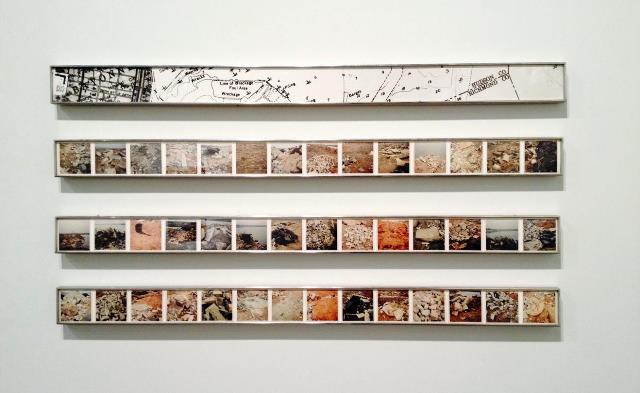

Navigating Woodward Avenue feels like weaving through the rows of square polaroids from Robert Smithson’s non-site installation Line of Wreckage Bayonne NJ, 1968. The same syntax of heaped forms is present not just along the avenue, but all over Detroit. Piles rove the city limits, appearing and disappearing like new storefronts and blighted homes. Construction materials, rubble, detritus wind-blown into misplaced cairns, burned houses collapsed into a pile of charred kindling, fill dirt next to Heizer-sized holes where houses used to be, and bulldozers that appear as prehistoric creatures devouring schools. Exploring these mounds is akin to a new “Tour of the Monuments.”2

The Detroit landscape straddles precarious precipices: between sublime ruin and banal deterioration, destruction versus construction. The “romantic ruins” that quilt the city continue to visually define it, with pictures from driving tours of blighted neighborhoods3 and shutterbugs swarming the Packard Plant for the perfect postcard image to bring home. But just as prevalent is Smithson’s concept of “ruins in reverse,” the debris of construction to come: “This is the opposite of ‘romantic ruin’ because the buildings don’t fall into ruin after they are built but rather rise into ruin before they are built.”4 Detroit exhibits both of these ruins in one form, the past and the present sharing the same shape.

The implication of each pile is clearly signified through its individual components. Brick, gravel and crushed concrete imply progress and renovation. These piles are predominantly centered amid Downtown and Midtown. Meanwhile, household items, stuffed animals and collapsed homes demonstrate a destabilization of the domestic and are numerous in the outer neighborhoods. The piles of Detroit seemingly offer the Cliffs Notes of a current divide within the city.

At the end of his ‘tour,’ Smithson gives us the analogy of a sandbox, a grave-like vessel that is simultaneously a child’s play area. To prove the “irreversibility of eternity,” the sandbox is filled in one-half with black sand and one-half with white sand. A child then runs in circles hundreds of times around the box until all the sand has combined and become gray. Once the sand is mixed, it cannot be separated. Even if the child runs hundreds of circles in the opposite direction, it would only further the degree of entropy in the system.5

We cannot reverse the past, but in Smithson’s example, it is precisely this past that gives us the substance to build the present. The sands mix to gray, but the physical sand in the box has not changed, only its placement. However, examining the dichotomy of Detroit’s piles, there appears instead to be a material trade at play. Burned houses are slated for demolition and piles of trash will eventually be hauled away, but new brick and stone are solidly installed into a contemporary scheme. The amount of sand is not changing, but it seems the new is slowly replacing the old. Is this a calculated attempt to re-install the original divide in the sandbox?

These images provide neither a map, nor a tour. They serve only to document the un-authored, un-titled “earthworks” that mark the city. Soil, gravel, tires, trash: some the off-casts of a life disintegrated, others indicators of future ‘revitalization,’ but collectively marking neither a convergence of progress nor non-progress. Here they appear only as what they are, unified forms rooted only in ephemerality.

footnotes

1 Smithson, Robert. “The Monuments of Passaic.” Artforum: December 1967.

2 Ibid. An essay detailing a trip to the post-industrial landscape of Smithson’s hometown, Passaic, NJ,

and his identification of the decaying infrastructure there as ‘monuments.’

3 See: Van Laar, Timothy. “Showing People Around.” Infinite Mile: issue 22, Nov. 2015. http://www.infinitemiledetroit.com/Showing_People_Around.html

4 Smithson, Robert. “The Monuments of Passaic.” Artforum: December 1967.

5 Ibid.

|

| Robert Smithson, Line of Wreckage Bayonne NJ, 1968 (detail). |

|

| Robert Smithson, Line of Wreckage Bayonne NJ, 1968 (detail). |

|

| Robert Smithson, Line of Wreckage Bayonne NJ, 1968 (detail). |

|