As the number of new businesses opening their doors in or around Downtown Detroit consistently increases, so does the peripheral conception of a rebirth or contemporary renaissance taking place in the city. This notion is, in part, attributed to the all-American understanding of success and triumph which, according to cultural theorist Mark Fischer, relies heavily on tangible evidence of capitalistic existence in a formerly crumbling constituency—or in other words, through proof such as new buildings, new people, and the erasure of ruination. As Fischer points out in Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Zero Books, 2009), the interpretation of the success in regards to a capitalistic culture depends on the relative newness being applied to the culture. This sense of newness currently remains inadequate in the task of burgeoning the vastly marginalized and economically devastated neighborhoods of Detroit. The idea, then, coined by Fischer as “capitalist realism” refers to the belief that a reality—in this case, Detroit—has been “rescued” by capitalism—in this case, a proliferation of suburban consumers and business owners. This gentrification is only augmented by the sometimes tense “insider-outsider” perspectives at hand. Those who have lived, worked, and struggled in Detroit often for generations may feel a sense of betrayal as their homes are taken from them and offered to newcomers willing to pay higher rates. Detroit stands as one of the top most segregated city in America (University of Virginia), which works to visually intensify the class struggles and effects of gentrification on “insider” populations. These complex issues can be paralleled with a concept that Fischer uses to describe the application of capitalist realism on a society:

The new defines itself in response to what is already established; at the same time, the established has to reconfigure itself in response to the new…Tradition counts for nothing when it is no longer contested and modified. A culture that is merely preserved is no culture at all.

Within capitalist realism, a culture which faces economic turmoil might as well be deemed nonexistent to the American fabric. Under this misguided American mentality, the “Authentic Detroit” culture, then, doesn’t exist either. This theory makes it all the more enticing—and extremely accessible—for those with money and influence to redefine or reassign the authentic Detroit experience and identity.

Recently, many major conglomerates have come up with targeted ad campaigns centering on Detroit and subsequently thrusting it into the national media spotlight. Probably viewed as normal sensationalism of an up-and-coming media buzz topic, but startlingly common to these ad campaigns is their predilection for assigning a particular identity to Detroit. These ads reveal what the respective corporations want to portray as the “authentic” Detroiter, and furthermore, buy into a long-lasting culture of the propagation of media manipulation in order to build a “real” Detroit story. Key to this compilation are the overarching motifs in the ads, which reveal a purposeful desire to validate the respective company through the use of color-coding: the inclusion of blacks in each ad are meant to authenticate the company, while the inclusion of whites represent the target audience it wishes to sell to. Furthermore, the inclusion of blacks and whites together reveal a constructed vision of a desegregated Detroit free of racial tensions or class disparities meant to comfort the consumer while still deeming their product as “authentic” or “real” (black). The following are examples from recent advertisements involving Detroit and Detroiter identity.

- Long John Silver’s - Nancy Whiskey

Themes: Nancy Whiskey’s as an authentic Detroit establishment

The scene: Whites as consumers at a fish fry

Music: Jazz, Blues

Imagery: Cooks and musician are black while patrons are primarily white. Intermingling of races is suggested. A prominent class distinction is made-- a white Vietnam veteran sits with blacks; jovial. Music (jazz, blues) and food (fish fry) reinforces the idea of traditional black culture and identity. Furthermore, the event being administered by blacks relays understanding that Nancy Whiskey’s is a black establishment catering to the diversified Detroit population—therefore, authentic.

- Apple iPad – Detroit Slow Roll

Themes: Story of community-building based on a black man’s idea.

The scene: Images of community engagement through group bike-riding and project planning.

Music: R & B

Imagery: A tradition of community bike-ride is assigned ambiguous origins, but suggested to be of black (Detroiter) origin through the attribution of Jason Hall. Images of white participants outweigh black participants. Jason Hall, a black man, is shown interacting with whites and in establishments typically associated with hipster culture. Jason Hall’s blackness is authenticating the predominantly white event validating a diverse and inclusive Detroit.

- Shinola

Themes: Revitilizing Detroit through industry

The Scene: Images of watch factory; mostly black workers

Music: Rock

Imagery: Shinola ads seem to be the most conspicuous in employing the idea of authentication through color-coded imagery and Detroit identity. This ad campaign takes a different route-blacks rather than whites are main figures in all images and videos related to the company’s image. In the “Our Story” video on the Shinola website, workers are almost all black. There is a young white male featured in a scene involving crafting of a watchband—this figure speaks to the target consumer audience that Shinola wishes to sell to. Besides his inclusion, the almost all black workforce plays the role of constructing an “authentic” Detroit product for the viewer. The end pan features a central white figure amongst a large group of people—mostly black.

-

The use of Muhammad Ali in new Shinola ad, Downtown Detroit. Ali, in an iconic pose, punches with his fist clearly confronting the viewer. Ali was a powerful celebrity advocate of the civil rights movement in America. The fist is provocative in that it is attributed to the idea of blackness and acts as a visual cue associated with the notion of “black power”. Photo courtesy of Instagram: @wheresshads

A young black girl. Image used by Jacques Panis (CEO) presentation on Shinola. March 2015. Photo courtesy of Rebekah Modrak.

- Chrysler Super Bowl Ad

Themes: Overcoming economic hardship; rising from ashes.

The scene: Industry, buildings, and recognizable Detroit monuments.

Music: Rap.

Imagery: Lacking people, this ad focuses on narrating a resilient Detroit. Prominent Detroit buildings, factories and monuments stand against brisk winter skies. Images like this lead to the rapper Eminem entering a brightly lit Fox theater where he confronts the viewer in the final scene. Eminem’s declares, “this is the Motor City”.

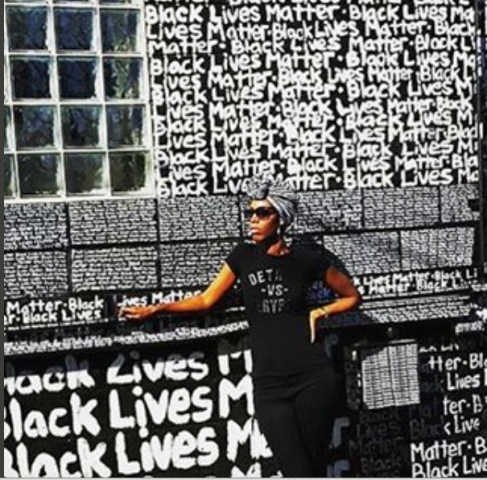

Detroit vs. Everybody image from @detroitvseverybodyllc Instagram page. The inclusion of Black Lives Matter speaks to the company’s target audience. Detroit vs. Everybody as a slogan is evocative of the pride associated with being a Detroiter.

Sources

"Detroit City: Ethnic and Racial Composition." US2010 Census. Brown University. http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/segregation2010/city.aspx?cityid=2622000

Fischer, Martin. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? New Arlesford: Zero Books, 2009. Print.

"The Racial Dot Map: One Dot Per Person for the Entire U.S." Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia. University of Virginia. http://demographics.coopercenter.org/DotMap/index.html |