Eli Gold and Melanie Manos

Gold’s performance, provisionally titled, The Monkey Chased the Weasel, took place Saturday, March 12, running throughout the day on a 9:00-5:00 schedule, with a break for lunch. Throughout these regimented office hours, Gold engaged in a relentless circuit of activities. Standing at a long pedestal outfitted with a bottle of iodine, a pile of cotton swabs, a finger-prick device of the type used to test daily blood sugar for diabetes, and a vividly magenta pile of removable sterile tips for the device, Gold dutifully swabbed his finger with iodine, pricked a finger and pinched enough to squeeze out the desired drop of blood, and then cleared the detritus into a wastebasket. Moving to a canvas hung on the gallery’s wall, gridded in pencil into a series of small boxes, Gold solemnly pressed his bloodied fingertip into the center of the next available box, leaving behind a wet, red fingerprint, sometimes surrounded by an irregular trace halo of yellow iodine. All this took place along the back of the gallery; having completed this routine, Gold walked to the front of the room where a concrete block awaited him in one of two positions, either sitting atop a chest-high pedestal, or on a landing pad of drywall on the floor directly across from it. Lifting the block from its resting place, Gold hugged it to his chest as he carried it across the room to the other position, either squatting to deposit it onto the floor, or hefting it up to the level of the pedestal. As the performance progressed, the block accrued a smudgy patina of bloodstain. Once the block was in place, Gold returned to the first position to repeat his routine, which took place more than 100 times over the course of the workday.

Gold supports himself and his art practice through professional manual labor that overlaps with part of his performance, and described during a later conversation the sense of isolation that can set in after a day of moving heavy objects with very little human interaction. And yet, there is an equally futile sense of non-accomplishment when one looks back on a workday spent idly shuffling virtual information, exchanging banal conversation in the coffee room, and attending meetings. There is something perhaps more concrete about, say, moving concrete. Nonetheless, the repetition of Gold’s performance, to say nothing of the racking of dozens of bloody fingerprints, leaves the viewer wondering if he can hold up under his routine, or may at any moment collapse beneath it. “I try to avoid anything I already know that I can do,” he said, of the physical trial he inflicted on himself for the purpose of the performance. “The risk of failure is always there.” Gold has done other labor-related performances, including Full Time, wherein he partnered with artist Rena Detrixhe to produce cement-cast pillows in sewn pillowcases, which were eventually sold at the precise cost of labor plus materials.

Walter De Maria argues in his 1960 essay “Meaningless Work,” that: “Meaningless work can contain all of the best qualities of old art forms such as painting, writing, etc. It can make you feel and think about yourself, the outside world, morality, reality, unconsciousness, nature, history, time, philosophy, nothing at all, politics, etc.” (According to De Maria, meaningless work must be done alone, lest it become a form of entertainment for others, so neither of these performances qualifies, as such.) Other works shown at 9338 Campau, notably the two-part investigation of labor process by artist Tsz Yan Ng (the first part shown at 2739 Edwin in 2013), deal with labor in a more literal way (in its second cycle,The Visibility of Labor, Tsz Yan physically casts the hands of every worker that contributes to the manufacturing of a specific little black dress). During our conversation, Gold referenced the work of performance artist Tehching Hsieh, whose one-year durational performance TIME CLOCK (1980-1981) involved the artist punching a time clock in his studio once an hour for an entire year.

One week after Gold’s performance, on Saturday, March 19th, performance artist Melanie Manos took to the air in her performance, Lofty Bitch, to address the challenging dynamics facing women in the workplace. A 30-foot ladder bisected the center of the gallery, braced at a hard diagonal. Sets of chairs for viewers were clustered on either side of the ladder, and a closed-circuit camera wall-mounted above the top of the ladder sent a live video feed into a monitor displayed at ground level. Manos’s performance, which she repeated twice in a four-hour window, took place in three sections with breaks in between for costume changes and, one presumes, physical recovery—like much of Manos’s work, the performance appeared to push the petite woman to the limits of her formidable strength.

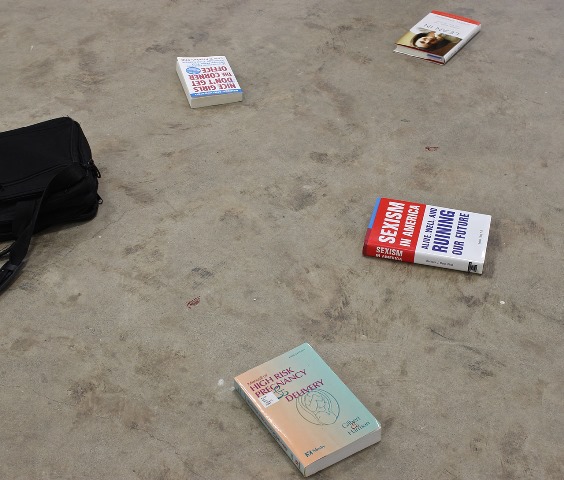

When Manos next appeared, she was outfitted in business attire—pencil skirt and conservative wool top, watch, roughly two-inch high heels—and carrying a purse and day planner, with a professional-looking briefcase-bag slung across her body. The clip of her heels resonated with authority and self-possession, and the tension in the audience was electric, for we all knew what was bound to happen next: Manos checked her watch, steeled herself, and mounted the ladder (topside). The climb, inhibited not only by her outrageously inappropriate footwear and clothing, but the clumsy negotiation of her business objects and bags that were endlessly getting caught up on the ladder, felt incredibly precarious. We, the second audience, were additionally aware that Manos had already gone through this taxing performance once and might not be able to do it again. Two thirds of the way up the ladder, Manos began to jettison weight in the form of books—her briefcase was full of self-help titles for professional women, including Lean In (Knopf, 2013) and, disturbingly, Manual of High-Risk Pregnancy & Delivery (Mosby, 2010). Having finally made her way to the top rungs of the ladder, Manos struggled to produce a tube of lipstick from her purse, which she uses to scrawl “I AM A CEO” high on the gallery wall, just below the camera. A precarious descent ended the second movement of the piece.

In some senses, the themes being dealt with by Gold and Manos—the tedium of paid labor, whether in an office setting or manual labor environment, and the unrealistic gauntlet presented by gender inequity, respectively—are relatable to the point of being mundane. Who has not suffered the crushing sense of ennui in the face of another soul-sucking day in someone else’s employ? Can any woman fail to produce at least one example of being faced with compounded expectations that make upward professional mobility an overwhelming struggle? And yet, the relatability of these performances point to something deeply flawed within the value system of labor that produced them. During Manos’s performance, the gallery’s entryway was papered with graphs from The Economist and an article on the subject from the New York Times, complete with reader responses. “It maps with my life in many ways though my circumstances are different from a corporate/business path,” said Manos, via email.

Can we dismantle an unjust system while working within its constraints? Is unpaid labor appropriate in the context of making a commentary on the state of labor? With their performances, Gold and Manos have done a magnificent job of physicalizing the problematic nature of work in America today (and consider that these are still the lucky people who have jobs at all!), but leaves us with few answers, in terms of the path toward resolving such matters. In a sense, what emerges from “lifework”, perhaps unintentionally, is a third question of labor in play—that of the artist. |

This text is by Sarah Rose Sharp in her capacity and does not, necessarily, reflect the views of different infinite mile contributors, infinite mile co-founders, the authors' employers and/or other affiliations.