Also Known As

Paul Goodrich + Eva Zielinski

To hide from possible aerial attack by enemy bombers, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, along with the famed architect William Bain, Sr. (who was appointed Washington State‘s Camouflage director) and Hollywood set designer John Stewart Detlie, hid Boeing’s operations by installing a faux neighborhood atop the factory. Detlie was well known for the set designs of A Christmas Carol (1938), Another Thin Man (1939), Test Pilot (1938) and Strike Up the Band (1940).2 The housing development lofted forty feet in the air and covered almost 26 acres, spanning the entire roof of the factory. Trees, roads, street signs, houses and schools were made of wire, plywood, fabric and canvas—never intended for any human inhabitants. Boeing's decoy town was incredibly detailed and complete with street signs humorously named "Synthetic St." and “Burlap Blvd.”. Fake hills were even constructed to offset the factory’s flat roof. “Houses, streets and plants were assembled like stage props out of plywood, clapboard, chicken wire and burlap, covering the plant’s roof during World War II. If any Japanese bombers made it this far east, the hope was that their pilots would mistake this for a quiet residential neighborhood” (“Civic Camouflage”. dornob: design ideas daily).3

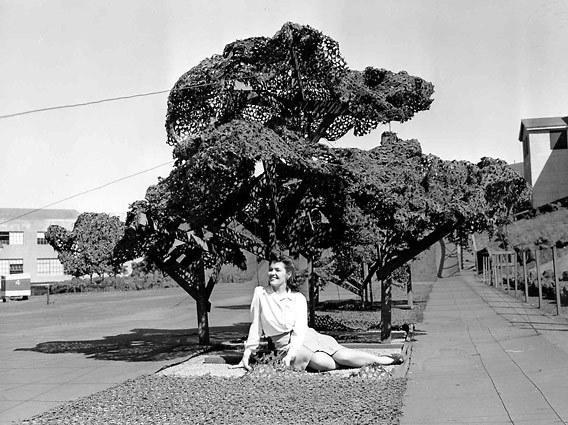

Image 1 (above) depicts the factory from a bird’s eye view, along with a detail of its camouflaged siding (image 2), which intended to blend the factory in with its surroundings. Many of the neighborhood roads led directly into the Duwamish River and King County International Airport. To further disguise the plant, actors were hired to inhabit the roof, pretending to have neighborly picnics, tend to their gardens, hang their laundry on clotheslines and take strolls down the town’s wooden streets. Many photos depict proud-looking women comfortably sprawled out amongst the quaint town. Such close-ups within the fabricated scenery resemble that of an early computer-generated landscape with edges appearing harsh, the color palette seeming stark and the scale of the buildings distorted. Little information is available about Boeing’s motive for having the photos taken. The images were publicly released after the war.

Most of the houses were around eight to twelve feet tall, but covered enough ground to seem convincing from a bomber’s perspective. The neighborhood trees were of typical size but resembled small, leafy deciduous trees rather than Washington’s usual conifers. Their trunks were constructed from skinny pieces of treated lumber with branches/greenery made from most likely a conglomeration of chicken wire and camouflaged meshing (the lawns, bushes and gardens were made of the same mixture). Most of the materials were later scrapped or recycled after the plant’s closing.

The site is now the source of the Duluth Timber Company, which “specialize[s] in salvaging and selling timber building materials from what it calls the "industrial forest””.4 Boeing’s neighborhood was disassembled and made available for public purchase after the plant closed its doors in 1946. Most of the chicken wire Boeing’s staff claimed along with the excess wood, which employees could have delivered to their homes for $34 a truck load.4 The factory sat until 2010 when Boeing, along with state, federal officials and representatives from local Native American tribes began a sustainable demolition with a goal to restore the property to its natural wetland state.5 Various hazardous chemicals and metals contaminated the factory’s footprint, which have consequently leached into the Lower Duwamish Waterway.6 Boeing used the title Something Old, Something New in February 2012 issue of Boeing Frontiers to describe the restoration project and claimed to have recycled around 13,000 tons of structural steel and 100,000 tons of concrete.7

1 Gates, Dominic. “Wrecking ball looms for historic Boeing Plant 2”. The Seattle Times. 13 January 2010. http://seattletimes.com/html/boeingaerospace/2010787200_boeingplant14.html

|

This text is by Paul Goodrich and Eva Zielinski in their capacity and does not, necessarily, reflect the views of different infinite mile contributors, infinite mile co-founders, the authors' employers and/or other affiliations.