|

Action game statement

I remember vividly the angsty, passionate, obsession of pre-pubescent kids with Magic Cards. They were everything. Recess after recess was spent huddled in a shady corner of the playground on hands and knees dolling out cards and making deals. Magic: the gathering was far too complex a game for us to figure out as 6 and 7 year-olds but it wasn't as if anyone was actually interested in the official rules of engagement. For us it was all about the trade.

Boy A covets boy B's shiny silver dragon. Boy A looks at his wares and offers up some kind of warlock emitting blue hellfire. Negotiations begin.

Without the governing principles of Richard Garfield's original game design, we used Magic Cards as currency and a cards worth was a function of the cool things the character could do as described on the back, multiplied by its aesthetic appeal. They were commodities to be traded, hoarded, and preserved for some far off future when their true value would be revealed.

I have 10 cards. Jamie has 8. Jamie has 1 silver card that is worth 4 cards put together. Therefore Jamie’s cards hold more value.

As an adult these cards and other types of trading cards have once again captured my attention. I am particularly drawn to the relationship between the way something looks, the way it is described and how much it is worth. To participate in society is to play a part in a discourse, one that labels other oriented bodies as outside of a norm. The trading cards that I have created represent a result of this discourse and provide tangible evidence for the processes by which we judge others. In life, bodies become translated from the way they look to words through a prism that skews everything that is not white or male, heterosexual or able-bodied into the liminal reaches of the spectrum. To be labeled a woman, raced, gay, or disabled—to be labeled—is to be marginal and particular.1 I see the act of engaging with a trading card as a distillation of the process of seeing and interpreting others into categories and types.

There is a long history of representing bodies in tradable and collectible media. Trading cards are just a recent permutation of an age-old custom. The year 1952 marks whenTopps trading company produced the first true set of baseball trading cards complete with player image, records and statistics, but travel back in history to the peak of European colonialism and you will find another kind of collectible card being disseminated throughout Europe and America. The exotica postcard.

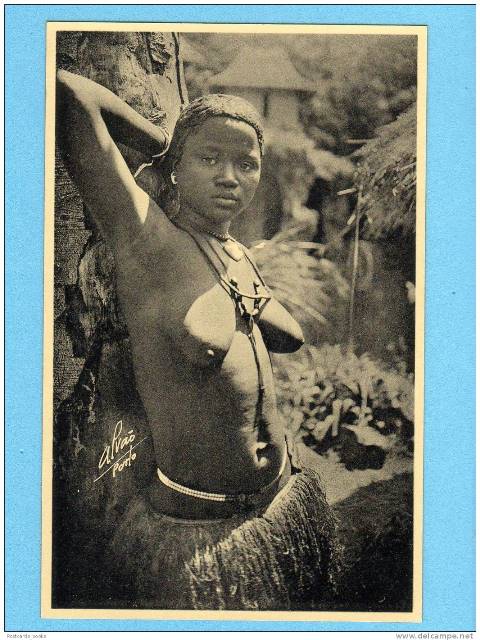

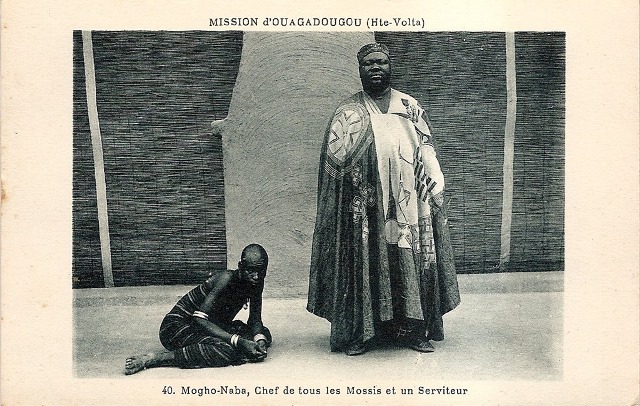

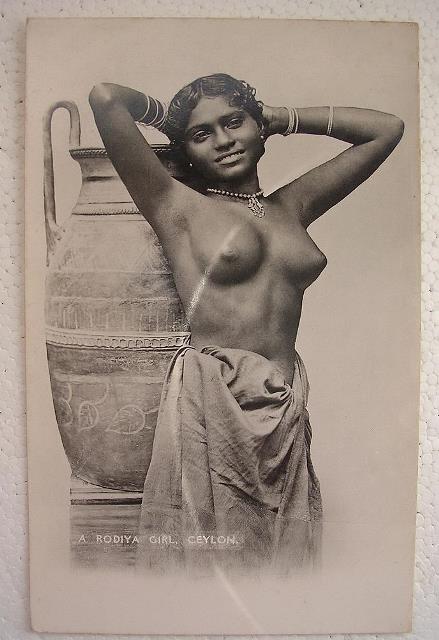

As Europeans colonized the world, the many people that found themselves in foreign lands sought to communicate the unfamiliar sights they encountered with their families back home. Picture postcards (figs. 1 - 4) not only met this demand, but provided imagery for a public at large that was starved for information. These images were marketed to arouse wonder, curiosity, sexually titillate and not to communicate facts. As a result, non-European peoples were depicted as types and objects of interest and categorized as such via pseudo-scientific labels and numerical coding. These images were extremely popular and voraciously consumed by the general publics of both European nations and the United States.

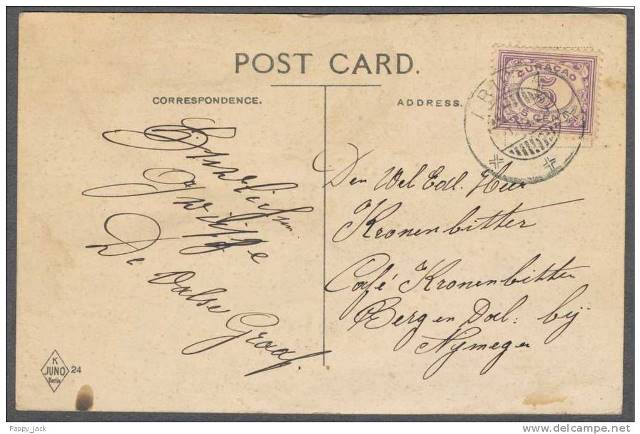

These postcards used language to fix people from other cultures in otherness and to hold their differences together in a nice, neat package. This process begins with the numerical codes and subtitles that categorize each image and ends with the personal messages sent through the mail. These messages are just the statistics and facts on the back of a baseball card in another form; they helped to interpret, codify, and place value upon the unknown world outside of the writers own geographic bounds. Other cultures became as flat as the two-dimensional representations on the postcards themselves rendering them safe and innocuous.

Une Type du Maroc 1026.12: “How enchanting were the brown skinned natives of this exotic land!”

These connections between my childhood play, my interest in image making and image control, and an almost obsessive fascination with depictions of difference in media output have allowed Your Body is My Wonderland: Action Game to take shape. Action Game cards come in non-standard sets of 5, allowing purchasers to trade with friends and other cards carriers. Collectors, also called A-Gamers, will eventually be able to make strategic trades based on established rules of play. Action Game is a permutation of a wider body of work called Your Body is My Wonderland that attempts to scratch the surfaces of the matrices that govern identity; matrices that are “naturalized, concealed, and protected from radical critique.”2 Only when the boundaries of the discourse are revealed can we begin to transgress its limits.

1 Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of identity. New York, New York: Routledge. 1990: p. 110.

2 Ibid., 111.

|