Oren Goldenberg, A Requiem for Douglass, 9 - 26 April 2015

Woodward Gallery at MOCAD

4454 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 48201

As groups including but not limited to the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.) continue to represent the interests of capital on a global scale following the Bretton Woods system and take to measuring the world according to development, it seems critical to understand what such development means. Development here is not strictly limited to neoliberal economics but also to the aesthetics and politics that make such an economic system possible. During the mid-twentieth century, examples of development according to international (now global) capital appear aesthetically linked to modernism with buildings such as Lafayette Park designed by Mies van der Rohe and the Brewster-Douglass housing projects designed by the firm Harley, Ellington & Day of Detroit2. One of the modernist projects, the Brewster-Douglass housing projects, becomes the subject of Oren Goldenberg’s A Requiem for Douglass, 2015, (fig. 1) in a commemoration of both their demolition and how their meaning disseminates throughout the lives they affected.

figure 1 |

|

Oren Goldenberg

A Requiem for Douglass, 2015

photo courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

In contradistinction and incidental to the myth of continual progress towards a(n) (a)historical sublime that is modernist utopia, development also represents a historical amnesia as trauma at the same time trauma represents itself as history. Remembering according to development becomes a perpetual crisis between the inability or unwillingness to forget and to know. However, things change despite development, the dissemination of which becomes apparent in A Requiem for Douglass.

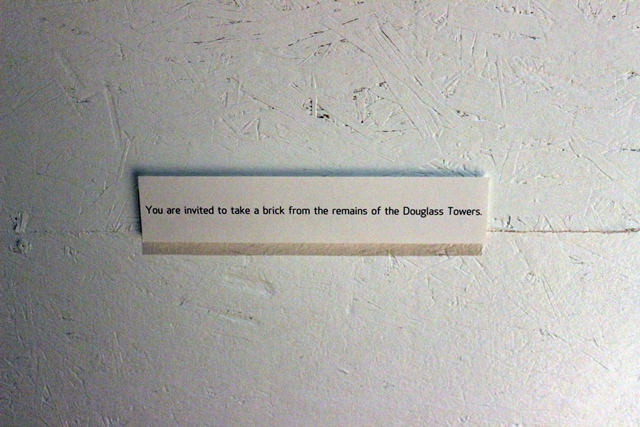

In A Requiem for Douglass, Goldenberg sculpts a tower in the shape of a Brewster-Douglass project high-rise (fig. 2). Made from bricks taken from the Brewster-Douglass projects after their demolition in 2014, a note on the wall reads “You are invited to take a brick from the remains of the Douglass Towers” (fig. 3). White plywood walls surround the sculpture, taking the shape of a Brewster-Douglass tower perimeter. Films featuring performances by the Gabriel Brass Band3, Art Lab J4 dancers and choreographer Joori Jung, Rowe Niodior African Dance Company5, Chace ‘Mic Write’ Morris6, Bianca Ibarlucea7, St. Augustine and St. Monica Choir8 and Halima Cassells9 project onto the three walls facing the tower sculpture. A Requiem for Douglass is stipulated by Goldenberg to last until no bricks remain. The performance of A Requiem for Douglass, in its disappearance, traces the dissemination of a monument as Brewster-Douglass projects cum sculpture.

figures 2 and 3 |

|

|

Oren Goldenberg

A Requiem for Douglass, 2015

photo courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

Detroit becomes littered with forgotten monuments as development changes the surface of the city in ways meant to smooth-over history, flattening the landscape, as it did in the demolition of the Brewster-Douglass Projects, as I-75 Chrysler Freeway did Hastings Street, as Lafayette Park did Black Bottom, as the Olympia Entertainment District will do to the Cass Corridor. But what is a monument if not always already a vestige of lost cultures, cultures negatively affected by memory? Oren Goldenberg’s A Requiem for Douglass remembers the act of forgetting that becomes visible in the decayed development of Detroit, development built on the notion of modernization at the expense of the always already participation by lives and cultures in the city. By remembering the act of forgetting, A Requiem for Douglass offers counter-narratives to the seeming inevitability of construction according to development through the dissemination of the demolished Brewster-Douglass projects.

What is it to forget? To distinguish trauma from forgetting as two separate but not, necessarily, mutually exclusive processes seems counter to the (a)historical sublime posited by development. Development’s (a)historical sublime is the inevitability of future progress and our helplessness in altering fate. Such inevitability A Requiem for Douglass casts in doubt as visitors take part in the dissemination and disappearance of one of development’s promised futures. By thus locating memory within a liminal understanding, the future sublime promised by development becomes both knowable and forgettable.

To forget is to know non-knowledge and to know non-knowledge is counter to development’s claim to know the future unfolding. Development, as this text suggests, unifies non-knowledge with trauma to turn knowing anything other than its own ceaseless progression into trauma as well. The trauma inflicted by development becomes a casualty10-- but not causality to-- progress, as such narratives run counter to the stream or development.

A Requiem for Douglass connects causality to casualty in the Brewster-Douglass projects by telling of the lives affected by the towers. The celebrations at the site days before the towers’ demise accompany celebration as well as solemnity for the lives affected therein. The architects of the Brewster-Douglass projects certainly did not envision dancers, bands and poetry at the site of their disrepair and destruction. The belief in a ceaseless progression of development accompanied their founding. Progress for the architects of the Brewster-Douglass projects was towards a sublime notion of utopia we cannot know or forget and it is such sublimity that requires undoing in order to remember how to forget.

To distinguish trauma from non-knowledge is to recognize the play between forgetting and knowing that development’s (a)historical sublime ignores. In writing about the relationship of forgetting for Jacques Derrida and Frederic Nietzsche, Gayatri Chakravoty Spivak writes, “if we long to know we obviously long also to be duped, since knowledge is duping” (Spivak. “Translator’s Preface” in Derrida. Of Grammatology: pp. xliv - xlv). For Spivak:

Derrida’s understanding of such forgetfulness--via Freud’s research into memory--is that it is active in shaping our “selves” in spite of “ourselves.” We are surrendered to its inscription. Perhaps, as I have argued, in the long run what sets “Derrida” apart is that he knows that he is always already surrendered to writing as he writes… Nietzsche, paradoxically, knew even this, so that his affirmative and active (knowing) forgetfulness was a move against the inevitability of a knowledge symptomatically priding itself on remembering” (ibid.: xlv).

Thus, to Derrida, according to Spivak, forgetting comes to define an author’s surrender to memory according to the text. Goldenberg’s invitation for museum gallery-goers to take from a tower of stacked bricks taken from the Brewster-Douglass projects seems to surrender his sculpture to the gallery-goers and, thus, commemorate the act of forgetting. As the title suggests, celebrating the memory of a demolished building by a vanishing sculpture sets a paradoxical task for the artist.

The use of vanishing and disseminating sculptures have a number of precedents, including Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s stacked prints and individually wrapped candies and Robert Smithson’s monuments to entropy. In Gonzalez-Torres’s installations with stacks of prints and candies, the sculptures appear to vanish and re-appear using an endless supply of replacements. In Smithson’s monuments to entropy, time turns industry into obsolescence. A Requiem for Douglass seems different from Gonzalez-Torres’s sculpture in the way it concedes its properties to memory that a supposedly unlimited supply of prints or candies does not. Likewise, A Requiem for Douglass seems different from Smithson’s monuments to entropy in its decidedly celebratory and solemn regard toward its subject: the passing of the Brewster-Douglass projects. In addition to the visible dissemination of A Requiem for Douglass, the sculpture commemorates a once prominent feature of Detroit and a site of massive political struggle now lost like many of the buildings in the city.

In Detroit, the Brewster-Douglass housing projects became one of the more visible failures of Detroit’s development (fig. 4). Built in high-modernist style, the housing projects supposedly attempted to alleviate some of the distress caused by housing crises between the 1930s and 1950s as a result of several millions of African Americans leaving and/or fleeing the southern United States and who also faced discriminatory housing practices11. By the time of the closing of the last remaining towers in 2008, wherein about 280 families lived in buildings once meant for between 8,000 - 10,000 residents, blight and neglect already claimed much of the buildings. Squatters and scrappers went to work.

figure 4 |

|

Brewster-Douglass towers demolition on 16 July 2014

photo courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

Why speak of trauma? As mentioned earlier, development would prefer not to speak of trauma and ignore failure. In scenes of such failure made visible in images categorized sometimes as “ruin porn”, ironically, the lives affected by such failure sometimes seek its censorship. Such censorship ignores the trauma inflicted by development and, thus, cause for recourse to any future development. By speaking of trauma in the Brewster-Douglass projects, a trauma made visible in A Requiem for Douglass (fig. 5), the narrative of development, particularly that represented by modernism, ironically seeks to ignore trauma where it happens in order to remember a future (utopia) we cannot know or forget and, thereby, repeats the same trauma ad infinitum.

To speak of the towers as merely a failure in development ignores the trauma felt by such development. In speaking of such trauma as it relates to the Brewster-Douglass projects, it reveals different narratives bound to the development and its destruction. The Brewster-Douglass projects represent the failure of a particular epoch of history according to development while also representing trauma for the lives affected by the failure therein. For sure, the Brewster-Douglass projects also represent some pleasure despite the failure, but, for many, the projects represent the ghetto, impoverishment and the trauma associated with much of poverty in the United States. Indeed, as Goldenberg says, the majority of the people he (Goldenberg) believes "felt the projects were amazing vehicles for social mobility, and especially connected community, that is if they lived there between the 50’s-80’s (the latter also existing past the 80's)".

figure 5 |

|

Oren Goldenberg

A Requiem for Douglass, 2015

photo courtesy stephen garrett dewyer |

The end of trauma is the will and ability to forget knowing and knowing the violence at its beginning. It is important to remember trauma has an end since, in Detroit, the surroundings become marked by homes torn to pieces, some until nothing remains but the staircase and basement or an abandoned factory designed by Albert Khan. The sublime turns the ruins of Detroit into absolutes, as if they were and always will exceed our capacities to know and forget the traumas induced by their development.

In A Requiem for Douglass, trauma and forgetting become distinguishable through the dissemination of bricks taken from the demolition and construction of the Brewster-Douglass projects. By distinguishing forgetting from trauma, A Requiem for Douglass links development to a flattening of history that both represents a historical amnesia and an inability to forget. Such flatness turns forgetting into its own monument to loss, a historical amnesia marked by the trauma of an unwillingness or inability to know a particular history. The dissemination of trauma invariably involves forgetting as well as remembering since both constitute the surrender of the writer to the text and the consequential meaning that comes from such surrender. A Requiem for Douglass demonstrates the dissemination of a trauma that development can neither forget nor remember and, thereby, surrenders such trauma to the play of meaning that happens between forgetting and remembering that development can and will never achieve. By focusing on the aesthetics of development, as does A Requiem for Douglass, the play between meaning, not just in terms of beauty but also in terms of knowledge, becomes critical of development by showing the limits behind its economic motivation. Not knowing but knowing trauma becomes the historical conditions of development. A Requiem for Douglass remembers the Brewster-Douglass projects in order to forget them in a process of disseminating bricks that contributed to their development.

Detroit Future City. “The Detroit Future City Executive Report”. 2012: p. 5. http://detroitfuturecity.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/DFC_ExecutiveSummary_2nd.pdf

Goldberger, Rob. “Robert Moses, Master Builder, is Dead at 92”. New York Times. 30 July 1981. http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1218.html

Oren, Goldenberg.

http://www.orengoldenberg.com/

Spivak, Gayatri Chakravoty. “Translator’s Preface” in Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London. 1997: pp. xliv - xlv

1 A project created by Oren Goldenberg as the final iteration of his series The Future is Changing: Rituals for Spatial Change. The film Brewster Douglass, You're My Brother is at http://www.orengoldenberg.com/videos/40241661

2 Today, Detroit Future City represents one of the larger development projects in Detroit (http://detroitfuturecity.com/). The Detroit Future City Executive Report states it hopes to “become a living framework for change and development in Detroit” (Detroit Future City | 2012: p. 5).

3 A band from 1856 Santo Domingo that migrated to New Orleans and continues in Detroit as a second line brass band. The band performed a dirge and celebratory at the Towers.

4 a non-profit organization dedicated to providing a space for performing arts with the intent to build a larger, stronger dance community in the city of Detroit (http://www.artlabj.com/). Joori choreographed some of the dance numbers with her troop and was not involved with Rowe Niodior. She provided practice space and helped Goldenberg direct her dancers at the shoot. Her dancers were involved in dancing/movements within the towers.

5 an African dance company dedicated to the African Culture. The company performed a libations ceremony and an african dance number in the courtyard of the towers.

6 a poet/emcee in Detroit who co-wrote the sermon/poem with Goldenberg, which were then performed in the courtyard of the towers.

7 an artist in Detroit (http://biancaibarlucea.tumblr.com/) who organized the lantern launches and has done similar projects in the Cass Corridor.

8 a Roman Catholic choir in Detroit

9 a Detroit-based artist/community advocate who performed the sage cleansing ritual and helped awaken the spirits still left in the towers (http://www.infinitemiledetroit.com/Halima_Cassells.html).

10 Robert Moses: “I raise my stein to the builder who can remove ghettos without removing people as I hail the chef who can make omelets without breaking eggs” (Goldberger, Rob. “Robert Moses, Master Builder, is Dead at 92”. New York Times. 30 July 1981. http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/1218.html)

11 see redlining

|