a review of "Cosmo Whyte: Wake the Town and Tell the People”

Clara DeGalan

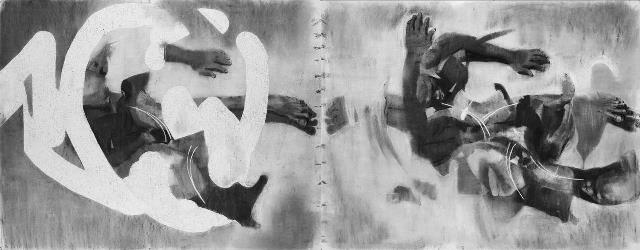

From Black Star Liners by Fred Locks, 1975 I learned about The Black Star Line through a chat with Cosmo Whyte as we strolled around “Wake the Town and Tell the People,” Whyte's formally taut, lyrical thesis show that was up for a too-brief handful of days at The Russell Industrial Center. Cosmo Whyte's subject matter spans flight, groundlessness, nostalgia and loss. Every image he makes floats on either a light or a dark void, or upon water, the ultimate void. Water made its presence felt again and again throughout “Wake the Town and Tell the People.” I was reminded of the strip of water one glimpses on the horizon of every card in the Ryder/Waite tarot deck—a visual binder as well as an indication that each image represents one step on a continuing journey. The subject of migration, of disintegrating borders and identities, is one Whyte engages with a graceful, almost ironic stillness. Just as his “Keloid” drawings (fig. 3) (as Whyte describes them, a visual distillation of “the body registering an event”) turn and flex upon white voids and his photographs sink into dark voids, his sculptures float in the charged space of the gallery, rendering it another sort of void—a snarled coil of weathered rope (fig. 1) , a pushcart made from shipping pallets (fig. 2). The ocean, and its transitory potential, evoked again, through some of the humble tools with which we attempt to manage and profit by it.

My impetus for wanting to talk with Whyte was an interest in how grounded even the concept-heavy three-dimensional objects in his thesis show seemed in the formal language of painting, which Whyte discusses in terms of poetics. His ideal poetic structure is the haiku. His goal is to pare each idea or form down to its essentials and then put it into a sensible dialog with other, similarly minimal pieces that aim to bind together into what seems not so much an installation as a sharply curated string of visual, formal and conceptual rhymes. The strengths possessed by one medium bolster the weaknesses of another- thus all become symbiotically woven taut. The formal rhyme that binds the sculpture made from coiled rope (which Whyte installed spontaneously, like one lyric bridging to the next) to the large, pulsating Keloid drawings morphs into a conceptual tie between the photos and sculptures. The risk of dissolution unto death skims the incisive paring-down process of all Whyte's work- fluidity and global transit carry physical and emotional risks, as well as economic, political and environmental ones.

One aspect that helps to bind the work visually—a primary concern of Whyte's—is that all of his projects begin as drawings. The finished drawings on display are, he indicates, the result of a long process of building up, erasing, redrawing, tearing down and scraping away. Though he does not think of the scraped down voids in his drawings as erasures, his frequent references to poetics invites comparison with current writer's practice. The other common aspect is the desire to not only re-write history, but un-write it—expose the ideological void in which we find ourselves at the dawn of the twenty-first century. In Whyte's practice, the essence of the refugee's experience is turned and twisted and examined via a sharp dovetailing of materials, forms and methods of making. Water is symbolic of death and renewal, and the oceans are the source of all life, as well as gateways of global transit and flight. To measure the distance to new shores, one is drawn look to the horizon. This is also how Whyte describes the experience of place and identity in his native Jamaica. “No one in Jamaica has indigenous status,” he explained. “Everyone is oriented to looking far afield.” |

This text is by Clara DeGalan in her capacity and does not, necessarily, reflect the views of different infinite mile contributors, infinite mile co-founders, the author's employer and/or other author affiliations.