| figure 1 |

|

Union label designed by Fredy Perlman for the Detroit Printing Co-op.

|

If you search the term “union bug” online, one of the first results to appear will be a Wikipedia definition of the term, accompanied by the above image, which Fredy Perlman designed for the Detroit Printing Co-op in the early 1970s. A union bug is a small marker that is included on materials printed at union print shops—they’re usually pretty discreet, appearing outside of a border or at the edge of printed material, and include the printer’s shop number. Often they say “Allied Printing”, an indication that all aspects of the work—from typesetting to printing to trimming and folding—were performed by union labor.1

Although illustrating the Wikipedia entry for “union bug”, this particular graphic is atypical in calling for the abolition of the state and the wage system. The graphic was designed for an unusual entity—the Detroit Printing Co-op—which was the site of the production of a number of visually surprising and compelling publications over the course of the 1970s, including the first English translation of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1970); the Black Star publication The Political Thought of James Forman (1970); the poetry magazine riverrun; several issues of Radical America; Red Star, an unofficial newspaper by students at Cass High School; and numerous books for Black and Red Press, which was run by Fredy and Lorraine Perlman.

| figure 2 |

|

Title page from the first English translation of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1970), published by Black & Red.

|

The story of the Detroit Printing Co-op, which existed from 1969 to 1985 in Southwest Detroit, is told in detail by Lorraine Perlman in her biography of her late husband Fredy’s life, Having Little, Being Much.2 She tells the story of a group of political activists who pooled their resources together to acquire an old Harris offset press from a defunct print shop in Chicago. They rented industrial space in a building on Michigan Avenue, near Vinewood, where they set up the printer and, eventually, a dark room that made it possible to process images. According to the Co-op’s rules, no single person controlled access to the equipment. It was available to anyone willing to invest energy into learning to operate and maintain it, so long as the needs were not for profit. The equipment was difficult to use—by the time they got the printer, it was already 50 years old. It required regular maintenance and, while printing multiple colors at a time was possible, it was difficult to do with precision. Nonetheless, Fredy Perlman, who engaged the most with printing over the course of the co-op’s existence, pushed the machines to experiment with overprinting, collage and typography in books and pamphlets that illustrate the evident joy that he took in the act of printing.

| figure 3 |

|

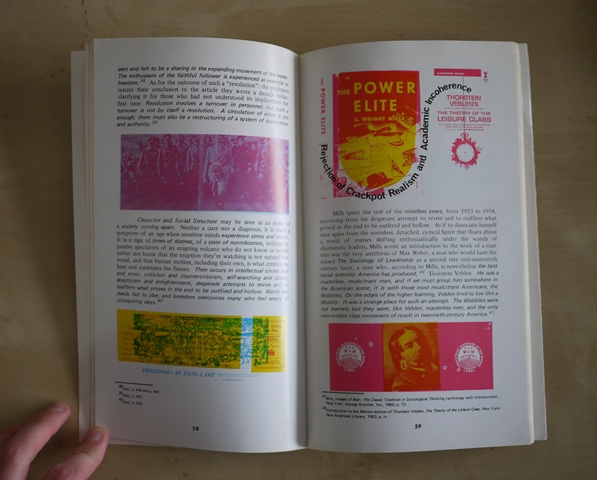

Interior spread from The Incoherence of the Intellectual (Black & Red, 1970), authored, designed and printed by Fredy Perlman.

|

Although Fredy Perlman was primarily concerned with ideas—he had no formal training in typography, printing or bookmaking—he designed books that were more complicated and interesting to look at than was strictly necessary. I would argue that some of his experimental energy stemmed from the political and economic structure of the printing co-op itself—the decision not to work for wages or monetize his time. The concerted attempt to work, to labor, as a printer, but not for money, led to design and printing decisions that would not be rational in a for-profit environment structured according to the rules of capitalism.

| figure 4 |

|

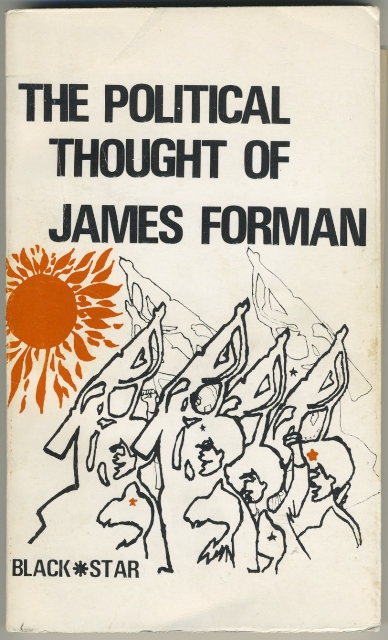

First edition copy of The New Freedom: Corporate Capitalism (1961) by Fredy Perlman, self-published in an edition of 91. Mimeographed and proofread by Fredy and Lorraine Perlman, artwork by John Ricklefs, books bound by Ricklefs and Fredy Perlman. This book was produced in New York City, before the Perlmans moved to Detroit.

|

The New Freedom: Corporate Capitalism, an early Black & Red publication that was first printed before the existence of the co-op, includes a note that reads, in part, “[t]he materials that went into the making of this book include mimeograph paper, heavy paper, fiber-board for the covers, and a small hand-cranked silk-screen mimeograph machine.” It goes on to say, “[t]he choice of materials was influenced by the extremely limited financial means of the author and artist, but both hope their attempt to make a book whose outward shape was consistent with its content has been successful enough to encourage others to follow their example.” Political texts tend to be quite dry in appearance, but here Perlman expresses the hope that others will be compelled to imitate his example of making a book that looks “consistent with its content.” That look is partly achieved through the use of inexpensive materials and a recalcitrant hand-cranked silk-screen mimeograph machine. His explicit narration of the tools and materials of production asks the reader to recognize the invisible labor that went into its production. It tells us: It isn’t easy to do what we’ve done here with this book, it requires skill and sweat, but you can do it too if you put effort and time in. And if you’re going to do it, try to make it look nice. Later, Black & Red publications that were printed at the Printing Co-op did not always include a note about the labor, but they were printed with the union bug, which acts as a reminder of the role of the worker.

Union labels, or bugs, were first placed on printed material produced by the International Typographical Union (ITU) in the late nineteenth century. The ITU was formed with the purpose of improving working conditions for typesetters and printers. The union bug has a precedent in printer’s marks, which have appeared in books since the late fifteenth century. Aldus Manutius’s emblem of an anchor with a dolphin wrapped around it is a well-known example that appeared in Aldine Press books. At the time, a printer’s mark represented both the publishing house and the print shop, which were one and the same place. If the union label descends from the printer’s mark, another descendent is a publisher’s logo (like the penguin on Penguin Books or the Doubleday logo, which is a modernized version of the original Aldine Press mark).

| figure 5 |

|

|

A label for a traditional union print shop + Aldus Manutius’s printer’s mark.

|

As the work of the typesetter and the printer became separated from that of the publisher and the author—one worked with machines and the other worked with ideas—printers fell more cleanly into the category of ‘worker’ than ‘thinker’, but there has always been overlap. Régis Debray has written about the role of the printer in the development of socialism. He describes the printer as “quintessentially a ‘worker intellectual or an intellectual worker,’ the very ideal of that human type who would become the pivot of socialism: ‘the conscious proletarian.’”3 It is interesting to look at the union label as a distant socialist cousin of the publisher’s logo. The union label communicates information about the print shop and the role of labor involved in production.

| figure 6 |

|

from left to right: IWW union bugs from Come!Unity Press in New York City, a print shop from Chicago, and New Media Workshop in Oberlin, Ohio.

|

The Printing Co-op bug is a bit different from a typical union bug because it communicates both information about the print shop and an idea. The Detroit Printing Co-op joined the International Workers of the World in the early 1970s. The language on the union bug—“ABOLISH THE WAGE SYSTEM / ABOLISH THE STATE/ALL POWER TO THE WORKERS!”—is part of the preamble to the IWW constitution.4 Lorraine Perlman writes in Having Little, Being Much that there was a resurgence of interest in the IWW in the early 1970s, as an alternative to the big unions like UAW, which were seen as racist, corrupt and hierarchical. I have come across several IWW union bugs from this time period, and the Detroit co-op’s bug stands out from the others because it directly commands the reader to act (“ABOLISH THE STATE!”). By comparison, New York City’s hand-drawn bug for Come!Unity Press has the tagline “Survival by Sharing”. The New Media Workshop in Oberlin reads, “AN INJURY TO ONE IS AN INJURY TO ALL”. These are statements that one can agree or disagree with, but they aren’t demanding anything of the reader. The Detroit Printing Co-op union bug eschews cuteness or romanticizing of what it means to upend the wage system. It isn’t hand drawn—this isn’t something you can do at home—it is machine made, all caps, insistent.

In late 1960s Detroit, many workers were resisting exploitation not only by employers but also by the unions that were meant to represent their interests. Worker-led Revolutionary Union Movements formed at the city’s car factories in reaction to racist union leadership, and joined together with black radicals, revolutionaries and intellectuals in the city to form the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in 1969. There is a story recounted in Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin’s Detroit: I Do Mind Dying5 of printing difficulties encountered by the editors of Inner-City Voice, a radical, Black-run newspaper that emerged after the 1967 uprising. They write that the FBI would visit shops that had printed the Inner-City Voice, accusing them of assisting in fomenting further rebellion. The print shops, intimidated by the line of questioning, would refuse to print subsequent issues. The ICV staff hit a wall when the International Typographical Union (ITU) leadership in Detroit voted to block printing the newspaper altogether, at which point no printer in the city would work with them. They finally found a sympathetic printer in Chicago.6

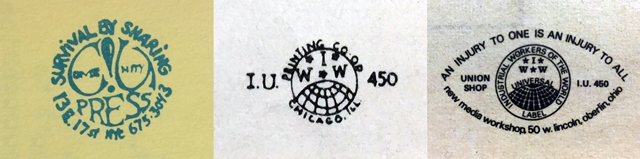

Following the difficulties of finding a printer to work with, members of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers—many of whom had been part of the Inner-City Voice staff—found it important to set up a print shop of their own. League member John Watson said, “[a]ssuming control of the means of production essentially means that you are at the first stage of assuming state power.”7 They set up Black Star, on Fenkell Avenue, where many materials were printed for the League. They also shared in the purchase of some of the equipment stored at the Detroit Printing Co-op. The day-to-day operations of Black Star were run by Helen Jones. Marsha Music, who printed at Black Star as a teenager, described Jones in an email to me as an “elder warrior woman”. She remembers Jones as a skilled printer who was instrumental in setting up the press. Georgakas and Surkin write that the book The Political Thought of James Forman was printed by Jones and Fredy Perlman at the Detroit Printing Co-op. Members of the League helped with the initial set up the Detroit Printing Co-op. Lorraine Perlman writes of a printer and graphic artist named Carl Smith, who spent a lot of time working at the Co-op, and, through the connections of another League member, brought in an electrician to “wire the large machines.”8

| figure 7 |

|

The Political Thought of James Forman, published by Black Star, was printed collaboratively by members of the Detroit Printing Co-op and Black Star. Cover drawing is by Aaron Ibn Pori. The printing credit on the back says it was printed at the “Revolutionary Printing Co-op, Detroit”.

|

At Black Star, there was a goal to generate income through printing, which would, in turn, allow the press to support itself. Jones, who taught League members how to print, “hoped to develop Black Star to the point where it could do commercial work well enough to … provide paid employment for League activists” as well as carry out the “printing chores” for the League.9 At the Detroit Printing Co-op, there was discussion of workers receiving wages for their time in the shop; however, the members decided against it. Lorraine Perlman recounts that co-op members were concerned that, if people received wages, it would give priority to projects done for money. It would also create a hierarchy between paid and unpaid co-op members, wherein paid members might be expected to take on maintenance and janitorial services. While some members did take on commercial print work at the co-op, they had difficulty in making it profitable. Lorraine quotes a co-op member’s observation that “[t]he capitalists can transform my labor into money much more efficiently than I can.”10

* * *

I first learned of the existence of the Detroit Printing Co-op in 2012, at an exhibition of Black & Red Press at 2739 Edwin Gallery (now 9338 Campau). It reminded me of a fantasy I had at an earlier moment of opening a free print shop in Detroit. I had read an essay by Cary Loren, “The Mimeograph Revolution,”and was taken with his description of the lively culture around Gestetner mimeograph presses in Detroit in the early 1960s. Loren writes that Monteith College, an experimental school on the campus of Wayne State, had a printing press with the policy to “allow students free access to print whatever they wanted.” He goes into some detail about the technical difficulties of printing well: “The entire process went smoothly for professional printers, but for most users (i.e., the do-it-yourself crowd) it was a messy business with torn stencils, ruined ink-stained clothes and smearing ink on the pages.”

I found Loren’s essay not long after I moved to Detroit in 2005. Within a few months and without much effort, I had acquired four large, used printers—a Ricoh color laser printer, capable of printing double-sided 11x17-inch sheets; an early model color laser printer (HP LaserJet 5) that took about 20 minutes to process a print; a 42-inch large-format color inkjet printer; and an HP black and white laser printer that came with a partially used toner cartridge that I never had to replace in the three years I used it. The first came by way of eBay and I acquired the latter three printers from Jim Snyder, a used office furniture dealer who had a warehouse on Franklin Street11.

At one point, I shared a studio with Nina Bianchi, also a graphic designer, and we occasionally imagined what it would be like to open a print shop where people could print “whatever they wanted,” following Cary Loren’s description of the gangs of artists who made use of free access to the mimeograph machine. We would follow the thread of this fantasy, imagining opening a storefront, maybe in Hamtramck, setting up the printers, letting people access them. We imagined the kinds of things they might want to print and how we’d manage such an operation. We couldn’t figure out how this could possibly become an economically viable model. We’d still need to cover rent after all. And, in my mind, I kept thinking of Kinko’s. Wouldn’t we just be a free Kinko’s? Why would anybody want to be a free version of Kinko’s? Yet, there was something compelling to us about imagining people standing around stacks of paper and active printers.

Printers are no longer critical for transmitting ideas today in the way that Régis Debray writes about or the way that they were for Black Star and the Detroit Printing Co-op. Our ideas are exchanged over the internet. But I still find something exciting about watching prints come out of a laser printer. The acts of collating, folding, binding and trimming that take place around a printer can create a particular kind of productive collectivity—an appreciation for paper and for machines, a feeling of potentiality. We can print whatever we want! We have made these things, which we can give to you! We can reproduce ideas and make them look however we want them to look! Nobody is making us design it a certain way, no one is telling us what text to put where, we just did it and printed many copies and we will distribute them.

When I found out about the Detroit Printing Co-op, and then read Lorraine Perlman’s Having Little, Being Much, I felt an immediate kinship with the project. Perlman mentions Joel Landy, a young printing enthusiast who spent a lot of time at the co-op. I realized I had met Landy while looking for studio space in midtown, where he owns several buildings. I remembered visiting his office and taking note of the fact that it was full of large-format and laser printers—way more than you would expect for a real estate developer. I asked him about all the printers and he said something about liking printers. It reminded me of my printing problem (at that point, I was essentially looking for studio space to store all my printers) and I had started to recognize hoarding old printing machines as a Detroit-specific affliction.

Thus, witness the uptick in letterpress print shops that opened between 2009 and 2012. There are obvious differences between the project of the printing co-op and the resurgence of interest in letterpress printing, and it maybe doesn’t make sense to compare them. Even at a print shop like Signal-Return that teaches how to operate the machines, there is no pretense that letterpress printing will again become a practical way to print large runs. Letterpress printing, at this point, carries a certain amount of nostalgia. But talk to anyone who does letterpress printing and they will tell you about the amount of time it took to print one thing or another, the effort involved, the paper they used and where they got it. Printing can be very solitary—there are plenty of people with secret, private print shops in the woods—but there are also many printers who welcome and foster the naturally convivial atmosphere that can emerge around print production. The large dinners that the print shop Salt & Cedar would organize make sense in this context. Print, eat, hang out.

A print shop that may have more in common with the ethos of the Detroit Printing Co-op and Black Star is Red Door Digital on Oakland Avenue, a commercial printer known as an ally to activists in the city. Another place is Ocelot Print Shop, a community silk screening shop, where people can learn to print, but it is not someplace you would go to print a book or even a quick flyer. A closer parallel might exist in the revived interest in Risograph printing—something that also exists in Detroit. Risograph printers allow for larger print runs and, like the Harris press at the Detroit Printing Co-op, can become difficult to operate in a way that colors register properly, so maybe Fredy Perlman would have enjoyed working with one. But I don’t know of anyone currently offering open access to their Risograph printers.

Something I am interested in exploring further, with respect to the Detroit Printing Co-op and Black Star’s print shop, is what to make of the printed formal attributes of the books, publications, pamphlets, flyers and newspapers. Is there a graphic language specific to materials printed in these environments? The project of printing in Detroit continues to be interesting. While the city is changing, there is still a persistent questioning of one’s relationship to one’s own labor and a respect for machines, even or especially old ones.

footnotes

1 Lincoln Cushing, “Proposal for Inclusion of Union Label Description in Bibliographic and Archival Cataloguing Guidelines” Progressive Librarian Journal, Issue #21 (Winter 2002).

2 Lorraine Perlman, Having Little, Being Much: A Chronicle of Fredy Perlman’s Fifty Years (Detroit: Black & Red Press, 1989)

3 Régis Debray, “Socialism: A Life-Cycle” (New Left Review 46, July-August 2007)

4 “Instead of the conservative motto, ‘A fair day's wage for a fair day's work,’ we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, ‘Abolition of the wage system.’” (http://www.iww.org/culture/official/preamble.shtml)

5 Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying (Cambridge: South End Press, 1998)

6 Dan Georgakas’s, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying (p. 18-19).

7 Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, p. 37

8 Having Little, Being Much, p. 61

9 Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, p. 82

10 Having Little, Being Much, p. 62

11 Franklin Furniture, now located at 5062 Lorraine Street, is still my favorite place to buy anything office related. Open Tuesdays and Thursdays, 8 am – 4 pm.

*

A printed version of this article will appear in Counter-signals 1 (Fall 2016). More information at www.counter-signals.net.

|