|

Introduction

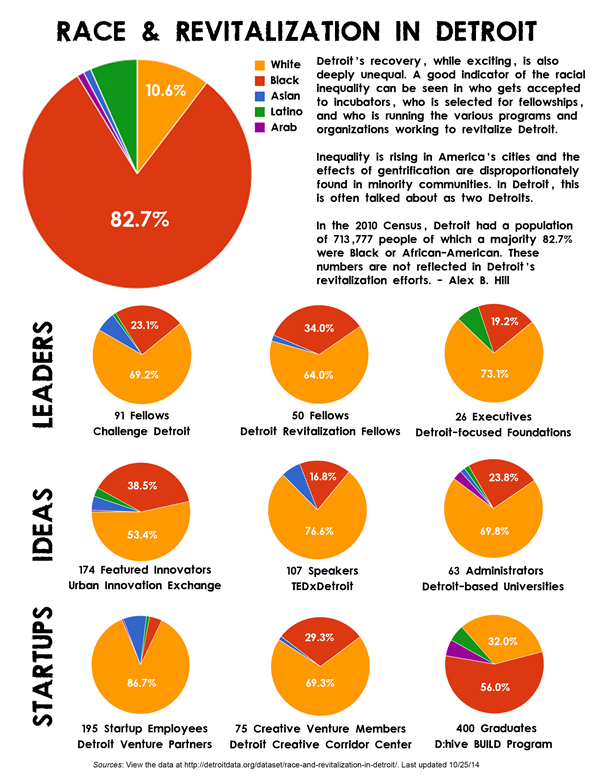

There are countless reports, maps, and statistics that demonstrate Detroit’s population changes over the years as well as the city’s decline. What is often overlooked in these figures are the social inequalities that fueled Detroit’s continued racial inequity. Structural racism is not easy to explain in a sound bite, but it has kept the scales tipped against Detroit’s black population for the last century. The effects of structural racism can be seen in the decades of black Detroiters being relegated to lower end jobs, rarely being promoted, being the first to be laid off, and being targeted for subprime mortgages.

Detroit’s revitalization is completely one-sided. The surge in investment in this majority black city is not going to black residents. I began noticing a troubling trend. First, at Whole Foods, one out of the ten featured suppliers were black. Then, again, when the 2013 Detroit Design Festival interviewed designers and one out of eight were black. A recent United Way campaign featured eight Detroit leaders and only two were black. I could only wonder why these revitalization efforts were so lopsided. Finally, I couldn’t help but cringe at TEDxDetroit 2013 where 80% of attendees were white coming up with “solutions” for Detroit, an 83% black city. To top it off, Wayne State University’s student population doesn’t even reflect the city with almost 50% white students and 20% black with only 9% of black students graduating in 4 years.

I’m not alone in my concerns either. There is overwhelming evidence that our cities are becoming more segregated and unequal. Not to mention the racist mortgage lending practices of our country’s largest banks decimating black home ownership in major cities, specifically in Detroit. One journalist has asked “Is there room for Black people in the new Detroit” and others have lamented “Detroit doesn’t need hipsters to survive, it needs Black people.” The New York Times received a lot of push back after a travel piece only featured White-owned businesses in Corktown which then brought out a counter article, “Black-owned businesses are quietly fueling Detroit’s resurgence, but no one’s talking about it.” Aaron Foley recently wrote an excellent piece for Bridge magazine, saying:

“WHEN “NEW” IS BASICALLY USED AS CODE FOR “WHITE” IN A CITY WHERE THE “OLD” IS “BLACK,” IT CAN DRIVE SOMEONE LIKE ME [A BLACK PERSON IN DETROIT] TO THINK THEY’RE OBSOLETE.” – AARON FOLEY

There is a very real concern over the shifting interests and populations within Detroit where the benefits of gentrification do not trickle down, but rather force more hardship on those who cannot pay to play. Increased property values don’t solve poverty or crime; they just make poverty and crime more concentrated.

Last year, I began attempting to track and quantify the issue within Detroit’s revitalization as it relates to racial inequity. After working for three years with families across Detroit, I could not help notice the absence of long-time Detroiters in development discussions, funding proposals, and the new “benefits” of a growing Detroit.

The title of this post, Black Problems, White Solutions, is a reflection that in Detroit problems are seen as being caused by black people, but the solutions are being powered by white people, neither of which is true.

Methods

My first challenge was that there is no demographic data (race, gender, age) published by small start-ups or even large corporations, or nonprofits. This meant that I would need to find the data myself. How could one white male possibly determine the race of hundreds of individuals involved in Detroit’s revitalization? Short answer: I can’t.

My next challenge was that I had to construct ideas about race in order to categorize individuals. I was extremely hesitant because I know that race is socially constructed, that individuals self-identify in very different ways, and that identity can and does change over time. It is important to note that discrimination affects minorities no matter how one self-identifies. Over a period of July-August 2014, I combed the websites of Detroit companies and start-ups for information about their staff. I, obviously, had to base my categorizations on my own assumptions and perceptions of race. I pulled headshots from individual biographies posted publicly on fellowship programs, academic profiles, and many “About” pages. All this data was then compiled into the database that I later analyzed.

My analysis brought to mind the PBS project where user can sort photos of individuals by “race” where the main takeaway was:

“CLASSIFYING THEM [HEADSHOTS] INTO GROUPS IS A SUBJECTIVE PROCESS, INFLUENCED BY CULTURAL IDEAS AND POLITICAL PRIORITIES.”

The article “Stereotypes drive perceptions of race” demonstrated that changes in racial categories “were driven by changes in the people’s life circumstances and common racial stereotypes.” There is also evidence that Latino individuals often choose to check the “White” box on the Census form as a sign of status. There is a similar issue where “Arab” populations are lumped into the “White” category by the Census Bureau. Our official systems to categorize race are both flawed and inadequate.

Note: “American Indian” was excluded even though there were around 2,500 individuals living in Detroit from the 2010 Census, the American Indian population makes up less than 0.5% of the total Detroit population, but also bore the brunt of early slavery in Detroit.

Results

What I found, unfortunately, confirmed what I had been seeing. Detroit’s revitalization is made up of a majority of white people. That isn’t to say that Detroit’s black population isn’t contributing anything to revitalization, rather it suggests that there is a deliberate racially unequal distribution of support and funding. In total 818 individuals were identified from fellowship programs, business incubators, universities, foundations, and other “innovation” programs.

Across all of the programs 69.2% of individuals were classified as White and only 23.7% as Black (1.6% Latino, 4.8% Asian, 0.7% Arab). Looking at this new data, it is clear that there is a serious imbalance of both opportunity and outcomes in Detroit.

*A version of the article also appeared on 16 October 2014 at http://alexbhill.org.

|