In a fascinating article published last Sunday in The New York Times Magazine, Jia Tolentino unpacked the widely spread word “empowerment,” which has a hefty presence in both feminist discourse and popular culture, appearing, as Tolentino notes, in advertising for everything from lingerie to self-help books to conferences.1 It offers up objects, experiences and role models that a woman can aspire to and consume (given she has the leisure time and the disposable income). It provides a framework for her to master the world and her identity within it, both outwardly and in. Seen in this light, empowerment for a woman is a signifier of an arcane acuity as well as something which can be bought and shrugged on, like a Coach leather jacket, projecting both her sense of self-worth and her economic leverage.

The idea of empowerment applies itself liberally, not only to what women may become or consume, but to what we may create. For example, where second-wave feminism styled it empowering for a woman not to cook, nowadays it can be empowering for us to cook—with locally-sourced, nutritious ingredients, giving us tacit approval to control what we put into our bodies. In the twenty-first century, the tasks and locations which used to imprison women, from kitchens to high governmental offices, are now freely appropriated and, ostensibly, mastered by us. This retaking has bled into contemporary art as well, since at least the 1970’s, when artists like Carolee Schneemann, Hannah Wilke and Marina Abramovic began placing their bodies into their work and testing the limits of what those bodies could do, endure and represent in contemporary culture. Women artists working in the Abjectionist and Earthworks movements began exploring the inside of their bodies as well, creating work that engaged viscera, menstrual cycles, violence and the discharge of birth, defining and exploring our special physiological connection to the earth on which we live. Freely mixing techniques, materials and practices that had traditionally been codified as “men’s” or “women’s,” these artists began a vital dialog with Western art that would define our voice in contemporary practice.

And then… something happened. Or maybe didn’t happen.

It seems clear that something got overlooked, swept into the shadows. You’d think we’d own our images by now, that we’d be able to look at one another and at ourselves and not have to sift through layers of cultural silt to get to what we really feel. Yet this is still not the case. I have interacted with a lot of powerful work made by women this winter, from Brenda Goodman at Center Galleries at CCS, to Nancy Mitchnick at Wasserman Projects, to Kari Cholnoky at David Klein, Nancy Mteki at N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art… The list goes on. The most recent show featured at Center Galleries, “Doubly So” (2016), stands out, however, in the extreme reaction it provoked in me that I still haven’t distilled. The discomfort “Doubly So” raised in me is due not only to its selfie-heavy content (a major difference between “Doubly So” and most of the other shows I mention above, with the exception of Nancy Mteki, whose gorgeous, confrontational work I lack the cultural perspective to properly include in this analysis), but to the questions it raises about what it means to be a “woman artist” today, and, more than that, how a woman looks at the work of women artists and the slippery nature of “women’s empowerment” as it applies to images of ourselves in contemporary art. After spending some time thinking about “Doubly So”, what really surprises me is how little has changed since women began confrontationally placing their own bodies at the center of their studio practice, with an eye toward empowerment, for themselves and for women in contemporary culture.

Which brings us to the selfie.

The selfie is as ubiquitous and fluid a medium of expression and identity as is the notion of empowerment, and, like empowerment, limns many different realms of social practice. It has as firm a footing in daily lived experience as it has attained in contemporary art practice—two problematic phenomena that connect women to both contemporary art and contemporary society. This connection is unsettling and raises several questions that are interesting in relation to these shows.

My first response to the work of Molly Soda (fig. 1) and particularly Sofia Szamosi (fig. 2) was that it was annoying. It seems pretty clear that not much in the American social media landscape currently is more annoying than the selfie.

| figure 1 |

|

Molly Soda

Selena, 2016

printed fleece blanket

60" X 50"

Photograph courtesy Clara DeGalan

|

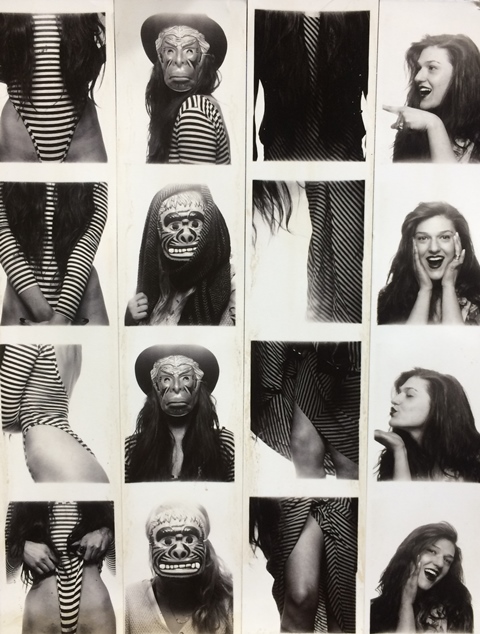

| figure 2 |

|

Sofia Szamosi

10 Years of Photobooth Self Portraits (detail), 2005-2015

194 original photo booth strips

8" X 23'

Photograph courtesy of Clara DeGalan |

Annoyance strikes me as an interesting response to any encounter, and encounters with visual art in particular. Annoyance, at least when I experience it, usually points toward confrontation with something that shakes my psychological foundations enough to cause extreme discomfort—points toward a deep personal taboo. The annoyed response, with its knee-jerk dismissiveness, effectively deflects that confrontation before it even begins to stir in its cave. Selfies, emanating from us or from others, are annoying, and, yet, irresistible. Who hasn’t unleashed at least one and experienced both the guilt and the deep pleasure, the empowerment that inflicting a selfie upon the digital universe entails?

Women artists on working in the “Selfie” genre2

If none of my photos had been nudes and there had only been the text I included in my zine (which is 50% of the zine) no one would be calling me vapid or trash. Doesn’t that have something to say about us as a society and the way we view women’s bodies [and our thoughts on them] having control over their bodies and the way they choose to share it?

-Molly Soda, responding to criticism of a series of selfies from her body of work “Should I Send This?”

I make object of myself and my privacy, which is a moment of fame. To turn the privacy as a public is a shelter for me. I feel privacy very painful.

-Liu Susiraja

I was being treated as if I was only a photograph of a naked girl long before I began taking photographs of myself naked.

-Audrey Wollen

These quotes are both intentionally and unintentionally revealing in the same way that selfies tend to be. It seems every artist employing the selfie has a personal gripe that leads them into selfie-making, but what that gripe truly consists of, outside of a general uneasiness and a desire to be comfortable in one’s own skin, is difficult for me to pinpoint. Soda points out that, even today, a woman displaying herself naked excites shock and rage. Liu Susiraja (fig. 3) acknowledges the role the selfie plays in projecting one’s identity (or desired identity) into the parallel ether of the Internet world-stage, and the resulting feeling of connection and affirmation that seems in short supply in the real world. Audrey Wollen (fig. 4) practically states that, since she already feels objectified, she might as well objectify herself in a studio practice, where, at least, she is in control of her image. But is that true? Here is where the biggest disconnect between women artists discourse about subversive self-portraiture and the work itself occurs. Looking at such work, I lose track of who is in control. Is the work empowering because the artist who made it is a woman? Because she is imaging herself? Yet she is exposed to the scrutiny of her viewer. Confronting Sofia Szamosi’s work in “Doubly So”, I was unable to distill the root cause of my annoyance—my first response, that the work didn’t feel current or vital, had some truth to it but it didn’t feel like the whole story.

This recalls a conversation I had recently with a friend who has taught photography at one of the same institutions where I teach drawing and painting. Discussing Szamosi’s work, it came up that both of us had dealt with a lot of student work along those same lines—self-portraiture that is confrontational, but vague as to whom it is being made by or for. It is always driven by feelings of extreme passion, anger and desire for self-empowerment in the young (usually female) artist. I made work like that in undergrad, too. Is it a phase every woman artist goes through? And why is it so consistently repeated, in form and content, down the generations? Why doesn’t it seem to be channeling anywhere, or moving anything forward?

One reason might be the general dearth of teaching about the women artists who blazed this trail outside of upper level “Feminist Art” or women’s studies courses. It is rare to find the likes of Carolee Schneemann, Adrian Piper, Ana Mendieta or Yoko Ono in the average Western art survey course, the kind all art students have to take. This phenomenon of repetition might also relate to the confusion, resentment and disengagement many of us experience when attempting to unpack and place the work of contemporary selfie-takers such as Soda. Despite my instincts to dismiss her work as self-serving and childish, the vitriol she takes for placing her body at center stage in her studio practice (tongue-in-cheek as it is, that doesn’t seem to matter to the public’s read) is haunting. I keep on wondering, why does this work make us so upset, particularly in light of the unshockable climate in which visual discourse currently floats? I don’t recall such outrage in the response to Paul McCarthy’s White Snow installation (Park Avenue Armory, 2013) for example, despite its pointedly offensive exhibitionism.

Which brings us to Secretary Hillary Clinton (fig. 5).

Secretary Clinton is where sexism, empowerment, woman’s image as it appears in popular culture and annoyance coalesce. She stands on the cusp of leaping into the office of ultimate power, raising female empowerment to an unprecedented level in United States history. She lived under intense public scrutiny since her husband’s presidency. Arguably, both her public image and her run for the Democratic nomination have suffered from confrontations with sexism, both glaring and subtle. And lots of people find her annoying.

There’s a strange similarity between my annoyed response to the work of Molly Soda, Sofia Szamosi and other women artists of the selfie and my (frequently, not always) annoyed response to Secretary Clinton. Both responses occur quickly and are followed gradually by a growing sense of uncertainty and second guessing. My initial response to Secretary Clinton is practically always driven by personal distaste—I don’t like her public persona, a self-presentation that includes tone of voice, her facial expression—she doesn’t seem like somebody I would trust or like. (This is separate from my regard of her politics, which is certainly a cause of my distrust but not the one I’m currently interested in.) The subsequent guilt I feel for not being one hundred percent behind the first serious candidate of my gender in the history of the American presidency only deepens my indignation, making me wonder why, in this supposedly post-gender age, I ought to feel any particular fealty toward someone with whom I share only a body. My initial response to selfie art is that it feels falsely empowering, disingenuous, self-centered and braggy. As I begin to analyze these two responses and they get murkier, more noticeably seasoned with jealousy and spite, the conclusion I arrive at every time is that I can’t make a decision about either. That, despite the fact that I am seeing what appear to be candid images of these women from all angles, I don’t really know how to look at them properly and thus cannot trust my reactions to them. Does this stem from some gap in my education? A generational gap? Is it a symptom of a deeper state of inequality in which women still navigate United States’ society? Why is it that, despite having spent the last forty-plus years looking at images of “empowered” women in art, politics and culture, they’re still so hard to see?

footnotes

1 Tolentino, Jia. “A Woman’s Worth” (accessed 17 April 2016)/"How 'Empowerment' Became Something for Women to Buy" (accessed 3 May 2016). New York Times Magazine. 12 May 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/17/magazine/how-empowerment-became-something-for-women-to-buy.html

2 Frank, Priscilla. "How Artists are using the Selfie as a radical weapon for Change". Huffington Post. 3 March 2015. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/10-artists-who-use-selfies-as-their-radical-weapons_us_55e7393ae4b0c818f61a303b

|