This text is by Ryan Harte in his capacity and does not, necessarily, reflect the views of different infinite mile contributors, infinite mile co-founders, the authors' employers and/or other affiliations.

| Détroit, très Brooklyn! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

examining gentrification and Detroit |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

They have destroyed viable neighborhoods or just shifted jobs and economic activity from one portion of the city to another. After completion, attention shifts on to the next revitalization effort. Perhaps this stems, in part, from a sort of identity crisis: in the face of a declining manufacturing economy, the nation’s largest company town wonders where it would be without the auto industry. Maybe it would be the West Side Industrial project in the 1950s, the Renaissance Center complex of the 70s (fig. 1), the People Mover, three casinos, a redeveloped international riverfront, urban farming, right-sizing, or de-urbanization, an idea to revert parts of the city back to woodlands. Any one of these would surely save the city. You have a multi-million dollar project? Here are the taxpayer’s dollars to build it!

There were other revitalization efforts, including blight removal (Lafayette Park), Olympic Bids for the 1952, 1956, 1960, 1964, 1968 and 1972 games. COBO Hall, the 1980 Republican National Convention and another wave of blight removal (crack houses). Renaissance Zones, Empowerment Zones and revitalization zones, Trapper’s Alley conversion in Greektown, tax breaks, and blight removal (empty decaying eyesores), hosting Super Bowl XL and the proposed M-1 “light rail” streetcar. Most recently, Fernando Palazuelo, a developer who filed bankruptcy in his native Spain, to then emigrate to Argentina and rebuild a fortune, is Detroit’s latest sensation. He purchased the abandoned Packard Plant sight unseen at the 2013 Wayne County tax foreclosure auction for $405,000. (After the top two bids of $6 million and $2 million fell through.)6 The local and national news erupted in optimistic boosterism.7 Detroit is desperate.

Finally, Detroit views gentrification as a savior of the city.† Built to accommodate its peak population of 1.85 million in 1950, a 61% decline in 60 years has left just over 700 thousand residents today.8 Reversing the city’s population decline is cited as Detroit’s biggest challenge (fig. 3), as the tax base is not here to support a city of this size. Gentrification is yet another idea in a long string of salvations meant to renew vibrancy. But what is gentrification? And can it be a driving force for renewal? Let’s examine.

The first contemporary use of the term ‘gentrification’ was by Ruth Glass in the introduction of her 1964 book London: Aspects of Change, which she uses to describe a certain transformation of London neighborhoods.

For as controversial the matter of defining gentrification is characterized, Glass’ usage evokes the very class conflict and displacement admonished today. Gentrification is quite a specific phenomenon. Suburban house flippers are not called gentrifiers. Nor are all urban developments are considered gentrification. The popular anger gentrification incites (e.g. “I see what you doin”10) implies, like Glass, a necessary condition for a change in social character of a neighborhood as higher socioeconomic status class takes over a neighborhood; either the initial residents are forced out of their neighborhoods and way of life, or otherwise receive some form of economic harm. ‡

However, economics does not explain the complete picture. Art engenders gentrification—specifically, the artist’s avant-garde aesthetic. The avant-garde toolbox makes art from the found object, seeks merit for the mundane and champions the unfavored. With the mindset of the avant-garde aesthetic, everything is an opportunity for art-making, including housing. Artists serve a social value in interpreting; in this case, artists interpret an industrial environment, repurposing the urban materials and redefining a residential style. They enter a declining district to make live-work spaces and communities. The American gentrification story was led by artists in instances such as SoHo in the 1960s. The archetypical feature of a gentrifying development is the loft as developed by artists. Artists moved into a deindustrializing SoHo for large spaces at low rents. A 1963 study of the neighborhood found the average rent to be $.81 per square foot per year ($7.75 in 2014 dollars based on CPI). Plans to run the Lower Manhattan Expressway through the neighborhood actually benefited the artists by minimizing rents and deterring developers.13 SoHo faced threats to be cleared for an urban renewal project to ameliorate New York’s housing shortage by providing a mix of low-to-upper income housing. Fortunately, renewal efforts were postponed when a subsequent study indicated “the district’s economic value lay in its function as an ‘incubator’. Roughly two-thirds of existing firms were small, and employed fewer than twenty-five people. In an environment where rent was inexpensive and overhead low, fledgling businesses had the opportunity to take root and even expand.”14 By 1968, the area had approximately 600 artists.15 Life magazine showed the nation loft living in March 1970 (figs. 4 and 5).16 The same year, New York Magazine toured an artist’s West Broadway, top-floor loft with “a skylight in his living room and several dozen large flowering plants reaching for it. He has a rock garden and slate floors and a series of custom-built nooks for his collection of Eastern statuary… The front 50 feet make a comfortable studio easily accommodating dozens of oversized canvases.”17**

Beyond lofts, an appreciation for grittiness, uncovering and restoring historic architectural details and pressing into an ethnic neighborhood are all variations of the avant-garde aesthetic. Artists transformed the view of SoHo cast-iron buildings, “once dismissed as a hideous relic of the late industrial revolution, were now treated like a sacred grove.”18 Rosalyn Deustche notices homelessness and derelict streetscapes becoming aesthetically imbued into the East Village neighborhood’s spirit. “As a process of dispersing a ‘useless’ class, gentrification is aided and abetted by an ‘artistic’ process whereby poverty and homelessness are served up for aesthetic pleasure.”19 This is the gambit of graffiti art, “ruin porn,” Murder Capital USA, each glamorizing the hard way of life many Detroiters face on a daily basis. Trend-making industries like advertisers, designers, luxury goods and art galleries are compelled to abandon traditional luxury office blocks (e.g., city centers, Madison Ave.) to locate in these newly trendy neighborhoods in order to fulfill their cool-hunting, trend-setting image by taking over historic building loft conversions. With the employers also come employees, along with accounting, legal, HR and IT services. The popularity of the neighborhood eventually far exceeds its capacity in the basic sense of infrastructure. Also, the avant-garde aesthetic shifted the narrative of American exploration to the built environment. New urbanism is the new, American frontier—Detroit is as lawless as the wild west. Neil Smith notes “urban pioneers, urban homesteaders and urban cowboys became the new fold heroes of the urban frontier.” Going further, “the westward geographical progress of the frontier line is associated with the forging of the ‘national spirit.’ An equally spiritual hope is expressed in the boosterism which presents gentrification as the leading edge of the urban renaissance.”20 Capitalism comes with a sales pitch. Individuals can carve out a living from a destitute landscape. Frontierism aligns itself nicely with capitalistic entrepreneurialism. The frontiersman, pioneer, explorer and conquistador all exploited the land and people they encountered, for the glory of crown, country, religious freedom and self-definition. To that, the glory and shame of gentrification. There are experimentations, coöperative opportunities and community organizations, as well as exploitations, marginalization and self-importance. Who are the winners and loser? Gentrification is defined by class and racial issues. When one population infiltrates a neighborhood and upends the neighborhood of another population, it is for economic advantage. But, the advantage is only temporary. The long-term benefits of gentrification are connected to the place, not the gentrifiers or the community activists, as they are all eventually priced-out. infinite mile contributor Shoshanna Utchenik sums it up nicely, “[h]ere is the artist-led gentrification formula: the intentions are good, or at least neutral, but positive developments quickly shift from benefitting the people to benefitting the place itself. The original inhabitants of the blighted area, and typically the artists, are removed with the blight, while the value they’ve all helped build stays behind. Residents are priced out of their homes or chased out by the cultural shift that cannot incorporate them.”21 Property values are assets, reward flowing to activists and long-time residents only if they have an ownership stake. Unless there is a mechanism to create an ownership opportunity, gentrifiers provide a value in wealth creation that is largely unpaid, only temporarily realized in reduced rents. Then a richer, more-privileged class upends the gentrifying population—with no end in sight. No less than a half dozen super-luxury developments under construction in New York City cater to the extremely rich.22 432 Park Avenue will rise to surpass the Chrysler and Empire State Buildings, have two-bedroom apartments starting at $9.7 million and top off with a six-bedroom penthouse. The building’s studios are reserved for support staff.23 In a global class society there is more than a lower, middle and upper class. No one is outside the reach of gentrification; wealth extends down the ranks and around the world. The city qua place may not oppose gentrification or land speculation and may even encourage it. The city qua people sees uneven rewards between renters and owners, between first-comers and late-comers. Ironically, today “lofts” are newly constructed instead of converted. For example, the current fashion commonly leaves floors as unfinished, poured concrete. The aesthetic motive of gentrification has also encouraged a few curious developments. The affluent suburb Troy created a downtown development authority to redevelop a stretch of Big Beaver Road where currently no downtown exists.†† Another suburban location recently attracting development attention is the intersection of Auburn and Squirrel Roads. Yes, thus springs up a downtown Auburn Hills.24 In 1988, Auburn Hills became the suburban home of the Detroit Pistons and in 1998 built the 1.4 million square foot outlet mall Great Lakes Crossings. Today, development is urban in feel. Auburn Hills is a true bellwether of the times. Gentrification is often described as a solely economic process. These suburban downtown developments, although not gentrification themselves, mimic a component of gentrification that is not economic but aesthetic.

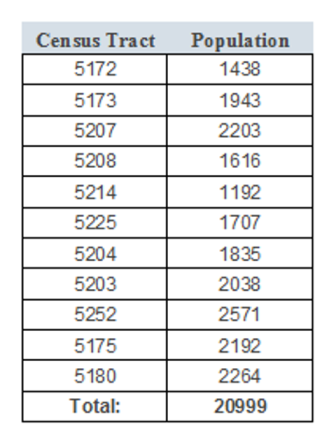

A regional political divide between the City of Detroit (Wayne County) and the suburbs (Oakland and Macomb Counties) prevents any meaningful coordination of regional services. The public bus transportation systems are divided at 8 Mile between DDoT and SMART. Currently, the urban-suburban divide is over cost responsibility of the regional water and sewer systems operations and long-term maintenance costs. On the other hand, displacing residents is not a necessity for development in Detroit. Many opportunities between rehabilitating abandoned buildings and developing vacant lots leaves plenty of space to come to Detroit and not be a gentrifier. Come join and empower the neighborhood. In some ways, with all its space, Detroit is unlike other gentrifying cities, it is partly a blank canvas. Detroit is reminiscent of the Commissioners Plan of 1811 laying out the streets of Manhattan and the way for development. No need to force anyone from their home with so much developable land. Cities look to gentrification to redevelop the ignored, struggling sections of town. In Detroit, much of the city is just ignored—left out of public and private investment. Current efforts are centered in three neighborhoods: Downtown, Midtown, Corktown and their immediate surrounds. The Downtown-Midtown-Corktown census tracts receive outsized attention while housing only 2.9% of the population.25 The investment is ignoring and distracting attention away from viable and valuable outlying neighborhoods such as Palmers Woods, University District, Rosedale Park, even Indian Village and the West Village miss out. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland classified only 2% of Detroit's census tracts as gentrifying. In fact, Detroit was last on the list of 55 cities the study ranked in terms of percentage of census tracts facing gentrification.26 However, the direct negative influence of gentrification is already costing Detroit. Developers are evicting residents. A renovation project downtown at 1214 Griswold Senior Apartments on Capitol Park evicted its senior-citizen tenants. The building was renovated and rebranded as “The Albert” inviting a younger lessee. Next door, at 1215 Griswold, the artists who converted the building to loft apartments were given 30-day eviction notices citing a Fire Marshall Inspection Report finding the building unsafe for its current occupancy. With so much developable space available, why are the current residents being evicted? It is cheaper to renovate an inhabited building than rehab a vacant one or build new construction. The proposed Red Wings arena will not develop entirely vacant land either. Three apartment buildings near the edge of the new arena and entertainment district on Henry Street were dealt eviction notices. The economic pressure of gentrification, mixed with the urban, frontier aesthetic, earned Detroit an epithet, “the next Brooklyn.” As the cultural center of art, innovation and gentrification, Brooklyn is the current nameplate for the avant-garde’s implementation. The New York Times attributes “très Brooklyn,” an adjectival phrase meaning very Brooklyn, to Parisians who encounter anything with “a particularly cool combination of informality, creativity and quality.”27 The employ of the aesthetic in both instances, Detroit and Brooklyn, is with such fervor that Detroit is regarded as the next frontier for Brooklynites pushed out by rising costs of living. Simply, Detroit is très Brooklyn. “Detroit may be a viable up-and-coming borough of Brooklyn itself.”28 These two cities are different in many ways, including demographics, economics, and spacial geography. Still, the fervor is matched in the huge undertaking of renovation, regeneration and reinvestment Detroit requires.‡‡ Back in New York, regulation—and lack thereof—played a role in SoHo’s developmental direction. The 1961 Artist in Residence program first allowed artists to live in commercial buildings, but nearly two years into the program only 81 of 146 applications were approved. In April 1964, the state legislature amended the Multiple Dwelling Law to allow artists to live and work in manufacturing buildings in New York City; however, with restrictions that kept many artists living illegally. In 1971, the SoHo Artists Association succeeded in negotiating with the City Planning Commission provisions to reserve 1000 lofts for artists. Plus the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated 26 blocks a historic district, ending the threat of high-rises. Yet today, SoHo is not known as an artist haven. Shortcomings in enforcement let in a stream of non-artist residents. With no rent controls, the large spaces became unaffordable. SoHo’s wild popularity undermined its vitality as a mixed-use neighborhood. In instances, the illegal occupancy of lofts allowed unscrupulous landlords to evict a tenant after making improvements to plumbing or wiring to make a space habitable in order to charge higher rents to the next tenant.29 Gentrification is likely an unstoppable force of economic nature. For smart gentrification, to reign an unyielding force, requires smart regulation. America considers our well-integrated communities a national value, but makes minimal efforts for such. The sheer supply of developable land available in Detroit is an obstacle to raising potential land values to a level that attracts development. Where the values are high enough, development yields luxury buildings. Developers are not inclined to produce mixed-income neighborhoods. Nixon’s Council of Economic Advisors determined “Investing in new housing for low-income families—particularly in big cities—is usually a losing proposition. Indeed the most profitable investment is often to demolish homes of low income families to make room for business and high-income families.”30 Marketing units as luxury commands higher prices and greater profits. The economic reality the free market provides is a supply of luxury units and abandoned vacant land, with nothing in between. Without smart regulation such as rent controls, this kind of displacement will continue. Plus, protecting low-cost housing increases the real estate values of the free market housing stock, driving rents closer to rates that support renovations and new development.

The ad resonates with a reclaiming of identity. It creates a desirability for what Detroit has plenty. The avant-garde device driving the ad shows a luxury, knowing “about the finer things in life,” that involves physical labor, withstanding economic hardship and valors craftsmanship. The shots embrace the bare trees and snow, the skies are tinted overcast. Furthermore, it resonates because the rise and fall of Detroit is closely linked with that of the auto industry. Eminem did the same nearly a decade earlier in the film 8 Mile. If gentrification is not only an economic phenomena but also aesthetic, its effects can extend beyond the physical market. A story or culture is different from real estate, where one’s ownership does not prevent another’s access to the shared story. It raises questions of who is entitled to claim ownership of an identity and who are the identity’s custodians. It is difficult to picture an aesthetic engagement that is not either exclusive or exploitive unless it is conscientiously built together. The newcomer’s approach should be a respectful facilitator of community development. Instead of taking the Detroit story, consider integrating into and collaborating on programs that develop the community in both its built and cultural environments.

As opposed to singular resource-intensive projects, the aid should be geared towards community self-definition. Ideally, community building efforts to enhance assets and create multi-faceted neighborhoods. Detroit does not need to be business friendly, manufacturing friendly, or convention event friendly. Detroit needs to be people friendly. And we are. Meet us and you will see the people here are full of pride and loyalty to their communities, including strong artist, literary, music and tech communities. As Shoshanna Utchenik writes, “[w]e, as artists, educators and activists, are doing a fairly impressive job of proposing answers to this question through our work. We are repurposing the materials and spaces laid to waste by Detroit’s cumulative disaster landscape, but we are also recognizing our power to make visible and useable the rich resources teeming within it.”33 Detroiters truly have an optimistic and independent spirit, open to making the world in their own image. Yet, to do so will require vigilance to guard against an outsized influence of corporate and billionaire interests, plus, to coax the market in a more socially productive direction. By capitalizing on the trend that desires vibrant central business districts and a housing stock of converted warehouses and restored historic buildings, opportunity abounds to bring in people and capital while building a tax base. And thankfully, this trend does not involve the destruction of entire city blocks for highways, entertainment complexes or stadiums. In fact, gentrifiers don't want highways or sports stadiums. They want bike lanes and independent shops, theatres, foodie restaurants and craft cocktail bars. Also, what could be more American or entrepreneurial than small independent businesses?

What happened next was the unfettered development invasion of the East Village and Lower East Side. And then Williamsburg across the bridge. Local leaders are fearful of stifling economic activity by examining proposals. There is a need for coordinated efforts between Detroit City Council, the State of Michigan, the Federal Government and foundations. A tendency is to ignore small, incremental efforts in favor of monolithic projects and billionaire tax breaks. The billionaires Dan Gilbert and Mike Ilitch have their own vision about how the future Detroit should look. Gilbert published and is implementing A Placemaking Vision for Downtown Detroit.35 What role the community’s ideas or desires made in the plan, either through consultation or direct contributions, is unclear. Neighborhoods also face pressure from institutional development. Wayne State University, University of Michigan-Detroit Center, Michigan State University-Detroit Center, Henry Ford Hospital, the Detroit Medical Center each maintain Midtown campuses. Some control large superbocks that interrupt thoroughfares. Asking for mindfulness in development will not curtail gentrification. So what policy is available to ensure gentrification is a positive force? As a partly economic process, gentrification “is clearly one means by which the rent gap can be closed, wholly or partially,” a solution is economics.36 One way modern capitalism had prevented exploitation of economic advantage is regulation. Smart regulation can protect current residents and communities, while shaping a path for future development. Consider the rise of the skyscraper. Urban landscapes are shaped in part by profit maximization, in part by building codes. Carol Willis explains in her book Form follows Finance as technological advances, namely steel-cage construction, allowed for buildings to become skyscrapers, cities introduced codes to limit their heights and bulks, and preserve light reaching the street. The resulting shape of skyscrapers was not because of a particular architectural school or style but a result of developers maximizing their profits.37 In New York, to maximize their buildings’ volumes, and thus rentable space, in response to the 1916 zoning ordinance, wedding cake style setback buildings came to dominate (figs. 7 and 8).

The local chapters of the National Association of Building Owners and Managers were very influential in fighting against building height restrictions in many large cities including Detroit, Philadelphia and Cleveland.38 Detroit had no zoning ordinance until 1940 and the city adopted its first master plan in 1951. Democratically, we can choose what kind of city we would like to live in and, then, develop guidelines and codes to create them. By designing tax abatement and development regulations, a city can define not only the physical environment in terms of lot lines, building heights, density and parking, but also environmental (building efficiencies, air quality, greenscapes), cultural (art spaces, live-work, bike lanes, ethnic enclaves), and social (affordable housing, mixed income developments, community health and education) environments. Detroit’s current framework, released in 2013, is “Detroit Future City.”39 The strategy is focused primarily on land use, infrastructure and economic growth. It does not address access to healthcare or education’s role in community and economic growth. Nor does it make zoning or policy recommendations to encourage diverse, mixed-income neighborhoods. An exciting initiative the framework suggests is to make use of available land to naturally filter storm water. This treatment could significantly reduce storm water volumes entering the wastewater treatment facilities and associated treatment costs. Gentrification is sought to solve the city’s fiscal and spacial challenges; by increasing the population and tax base as well as being an infusion of capital to save historic homes and renovate abandoned buildings. Despite the promise, gentrification benefits are uneven. Gentrification is localized to a minority of neighborhoods and has no incentive to respect the current residents or create communities we desire. It is unlikely any single project or policy will bring back Detroit. Vast sums of money are sunk into panacean projects. An alternative is wider support for many varieties of experiments and then further underwriting and repeating the successes. Meanwhile, residents should have control to democratically determine the shape and feel of their city.

1 “Bing: Ilitch company accrued $1.5-million tax bill during Joe Louis lease negotiations.” Detroit Free Press. Dec. 14, 2012.  26 Hartley, Daniel. "Gentrification and Financial Health." Nov. 6, 2013. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland |