“Scale is relative. I’m fascinated with vision, the relationship of the tangible to the visible.”—Claes Oldenburg1

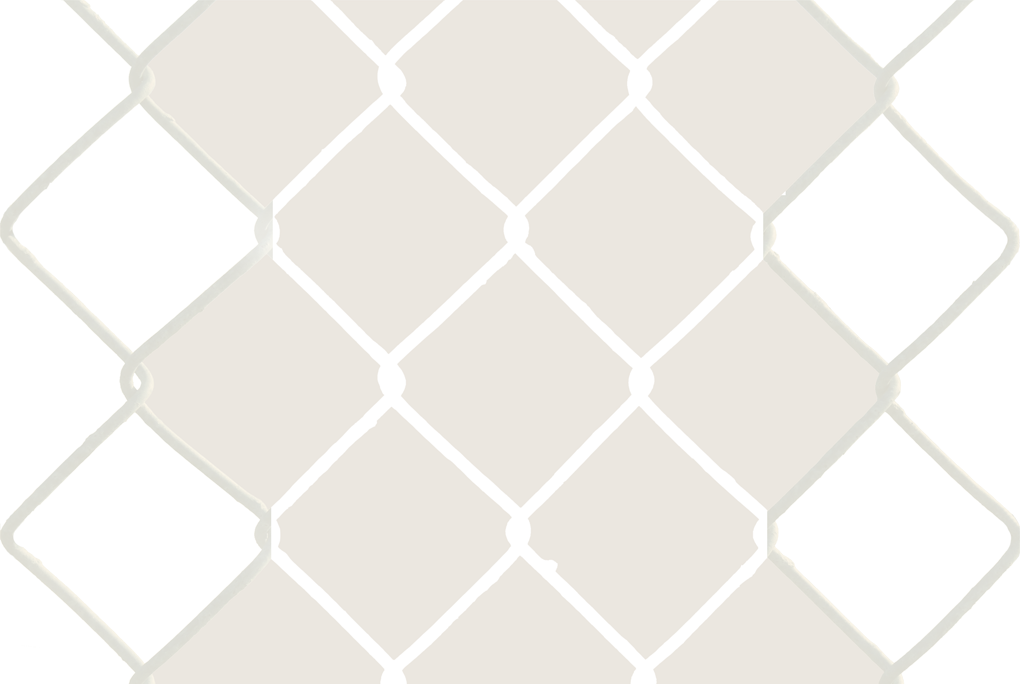

Best approached through the north staircase in the Contemporary Art collection, leading from the second floor down to the first toward the Kirby Street exit, Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Three-Way Plug (1970) at the Detroit Institute of Arts is a spectacular work of art, and not just because of its unusually large size of 58½ x 38¾ x 29½ inches. It changes from every angle, at every step, and, fashioned from mahogany veneer over wood with a moving viewer in mind, it impinges with an almost visceral force into the space of the spectator as an irrefutable obstacle.

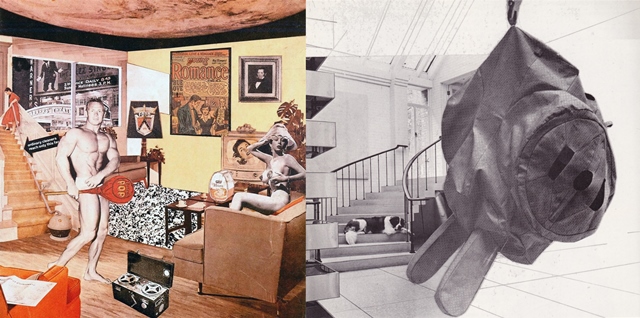

| Figure 1: a–d |

|

Claes Oldenburg, Giant Three-Way Plug at the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1970

Mahogany veneer over wood

Photo courtesy of Nadja Rottner

Copyright 1970 Claes Oldenburg |

In the public eye for his monumental outdoor sculptures of banal everyday objects such as a spoon or an ice cream cone, Swedish-born American artist Oldenburg ranks among the preeminent figures of Pop Art—together with Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. While much has been written about Oldenburg’s involvement with postwar consumerism, his readymade approach to artmaking, and the erotic appeal of his sculptures from an iconographic and psychoanalytically informed point of view, surprisingly little has been said about the complex theatricality of the objects’ experience. Thus, this essay supports a revisionist approach to normative readings of Pop Art focused on issues of subject matter alone. It considers how found images are manipulated formally and how the artist’s programmatic concern with the act of vision itself informs an alternative viewing experience. This essay, then, touches upon how the work can teach us something about the way we should experience everyday reality. This is a deeply modern concern with changing habits of vision that finds its reconfiguration in Oldenburg’s postwar neo-avant-gardism. Since the 1910s, avant-garde models for a politics of “renewed” experience have occupied a critical place in the history of twentieth-century modernism. Oldenburg intervenes in this history by attempting to help viewers make sense, or at least relate better, to a capitalist environment from which they are culturally disenfranchised. He does this by reinstating a more physical, imaginative, and intellectually stimulating experience of reality—one which had been deemed lost by critics of capitalism since the onset of industrialization. This criticism often finds its expression in artworks that circumvent easy intellectual comprehension, seeking to prevent an understanding of life in terms of readily classifiable (and, hence, manipulatory) concepts. Sculptures such as the Giant Three-Way Plug not only engage with commodified objects and their image representations in advertisements and mass culture, but they also address concerns with commodified experience (perceptual experience conditioned by commercialized culture into pre-ordained and habituated patterns of response that need to be broken.) One such modern strategy is the dislocation of objects and fragments of the real into unfamiliar contexts to make meaning in art contingent upon an experience of site.

In a comment on how the relationship between the sculpture of the plug and its place of installation affects its meaning, art historian Rudi H. Fuchs asserts that “form is identified with object. The object itself is not surprising but its identification with form and scale is… These forms are then introduced into a specific site where they work as something utterly different.”2 By manipulating mass, form, and images (be they representational, abstract, or semi-abstract), sculpture actively configures content through formal and material values. It is in his reliance on scale as a property of human vision that Oldenburg brings forth something novel. As Julian Rose ascertains, what is at stake in the artistic manipulation of scale is not only the “subject’s relationship to the [sculptural] object but the object’s relationship to architecture.”3 This means that a sculpture’s surrounding, be it interior or exterior, architecture or landscape, becomes charged with meaning as a viewer engages in a more active and bodily (rather than a contemplative, disembodied, and ocular) aesthetic experience which no longer prescribes a stable remove in a fixed location predetermined by a pictorial system of one-point perspective. Artworks in this tradition are composed with a main viewing point in mind. The plug, by contrast, requires an open-ended, anti-perspectival viewing with a spectator on a staircase. Recalling Oldenburg’s participation in the performance art in the intermedia-oriented arts scene of 1950s New York with Happenings and other new genres of artmaking that blended visual, literary, and performing arts conventions, the body of the viewer is liberated from being seated in front of a platform-like stage into situations of free and indeterminate movement.

The Issue of Projective Vision

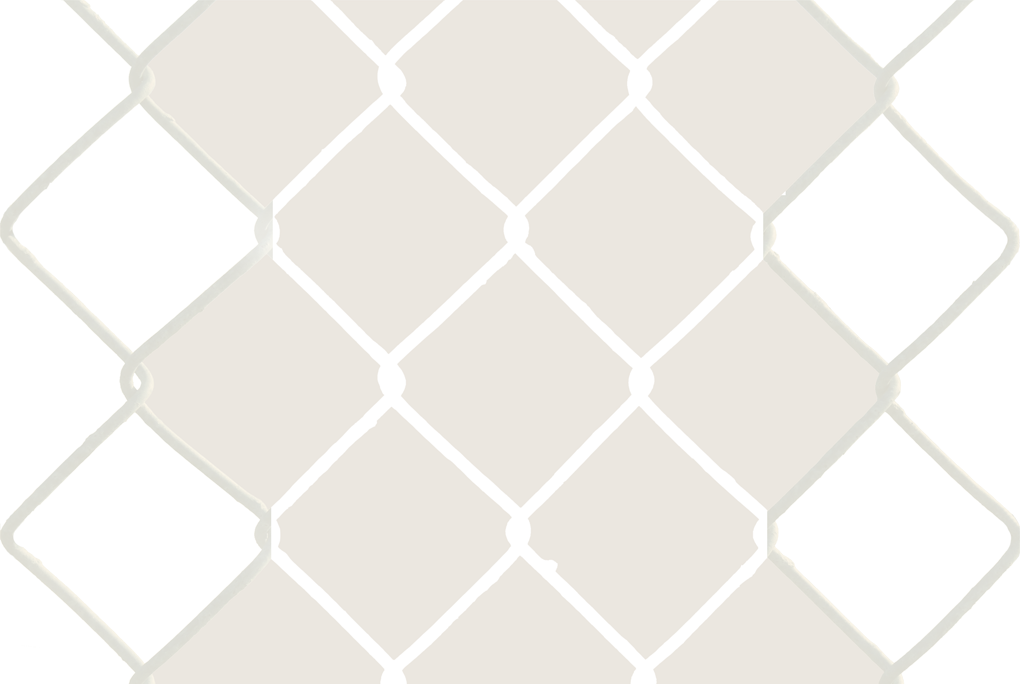

All perspectival systems are pictorial renditions of reality on paper and are projective in nature. They translate the three-dimensionality of the real into the two-dimensionality of the flat surface, and they imitate object-subject relations in everyday reality as we see them. One-point perspective was already known to the Greeks as a pictorial system that imitates how human binocular vision distorts the real by foreshortening and size changes. It couches the viewer in a stable subjectivity; distance and a fixed location guarantee visual overview at a remove, which, in turn, implies control.

| Figure 2 |

|

| Diagram showing the distortions of projective space as an observer stands on a foreshortened piazza of square tiles which narrow toward a single vanishing point. In an adaptation of the laws of human vision to the pictorial system of one-point perspective, this also represents the normative positioning of a spectator in front of an artwork in an institutional setting. |

The projective system that has most occupied avant-garde painters such as Pablo Picasso is the Classical system of one-point perspective in which the seeing subject is centered and placed in an all-empowering position of mastery. It is this very condition of stability and control that early modern painters programmatically rejected, inventing in the process new variants of anti-perspectival artmaking in a philosophical expression of a more skeptical worldview of man’s sway over life.

Despite the astonishing realism achieved by perspectival pictures from the Renaissance onwards, artists since the rise of Cubism have modified and refined their images in ways that violate the strict mandates of Euclidian geometry’s division of space into x and y coordinates at a right angle. Cubists, Dadaists, and Surrealists, for example, introduced a wide range of multifocal and illogical spatial systems, violating rules of perspectival space and linear time. The philosophical problem of perspectival vision has been how we can see the world accurately (i.e. the issue of realism). The Gestaltists of the early twentieth century rephrased this question by asking how the world looks as it does in images and how the human eye-brain apparatus processes the real. They established the fundamental scientific laws of human vision through empirical study of how we perceive; these laws then fueled investigations of phenomenology in later philosophical inquiries of the 1950s. Oldenburg’s realism, then, is not a standard realism of transparent naturalism but a procedural realism that foregrounds otherwise intangible procedures of vision by regrouping the perceptual as an experience of seeing and feeling.

A concern with vision is a concern with the structure of human experience and consciousness, of how we construct the real as we see it while simultaneously maintaining an insistence on the existence of the real as real. In his now exemplary publication in Gestalt psychology, The Perception of the Visual World (1950), James J. Gibson bases his examination of how we see on the distinction between the “visual world” and the “visual field.” Before we can ascertain how the two are related, we need to understand, he argues, that the former refers to the real and the latter represents the pictorial appearance of it in the eye-brain response of the viewer who creates a retinal picture as the result of physical stimuli of light, texture etc.4 It is this foundational distinction that dominates a Western culture of ocular visuality that separates the world-as-it-is (in its three dimensions) from the visual field-as-we-see-it (in its two dimensions.)5

Oldenburg’s art thematizes this dichotomy when he pronounces programmatically, “I’m fascinated with vision, the relationship of the tangible to the visible.”6 He takes it as a starting point and then undermines it. He imbues the image of the visual field with a lost physical dimension that is not an imitation of the real by means of techniques of illusionistic representation but a creative fashioning of new irreality. In order to do so, Oldenburg breaks with the foundational laws of perspectival geometry, which guarantee illusionism. Scale functions as an important value in this system. “Scale is relative,” Oldenburg asserts, as it is now determined by the artist freely, and no longer presents an absolute, fixed value of everyday perception.7 Oldenburg exaggerates the flatness of the seen by resorting to abstraction, as well as intensifies the three-dimensionality of the real as he stages the drama of vision in objects that he rebuilds with altered physical appearances set in unconventional contexts with exaggerated qualities: very shiny, very large, very soft. Thus, we “feel” the body of the plug more affectively. Oldenburg subscribes to the modern belief that a viewer can learn to see the real with the eyes of an artist who is trained to create a visual field and view art as a formal configuration of shapes, textures, colors, and spaces on flat plane. Oldenburg’s art is procedural and experience-based, engaging with structures of human vision by replicating how he sees the real and passing it onto the viewer.8 As he declares:

I have always felt the need of correspondence between one’s art and one’s life. I feel my purpose is to say something about my times… for me this involves a recreation of my vision of the times… my reality, or my drama-reality, and this demands a form of theatrical nature… like the film or theatre… I am making symbols of my time through my experience… every instant is the drama and my art is the record or evidence.9

Oldenburg’s sculptures are conceptually intertwined with his Happenings (beginning in 1960). In his experimental theater, he stages everyday objects in unfamiliar situations of encounter: oranges are juggled instead of eaten and a large, soft lip prop falls from a ceiling down onto an unsuspecting audience. In his writings on the plug, Oldenburg describes the theater practice as the drama of dislocated viewing, linking the production of sculptures and performances conceptually and historically:

The Three-Way Plug has created many new experiences for me, not at least of which is the placing of the finished plug, which is a form of theater. The logistics and circumstances of sitting huge objects (always with an audience) are what became of my ‘happenings’—that “Theater of Objects” in a new phase.10

In rejecting traditional viewing conventions of frontality (the convention of the proscenium stage in traditional theater) in favor of an experience of simultaneity and multifocality, a new post-dramatic, wordless, and anti-narrative theater of vision establishes the viewing subject as mobile, decentered, and nomadic. It presents several centers of attention simultaneously in a vision of everydayness that lacks the possibility of full oversight, is illogical, border-crossing, shape-shifting, hallucinatory, multisensory, embodied, and corporeal. The barrier between viewer and spectator is eliminated as physical distance is reduced.11

A Complex Theatricality of Vision

Oldenburg situates large-scale monuments such as the plug both indoors and outdoors in public locations across the country, capitalizing on how a change in size becomes dramatic in a break with normative object relations. Although familiar with the quality of an object’s size as something we can objectively measure, its relationship to scale as a property of ordinary vision necessitates a brief explanation. As psychologist Gibson establishes, while size in the visual world remains the same, we experience the size of objects in the visual field as changing. At close proximity an object appears larger, while at a distance it appears smaller because human vision is subject to perspectival distortions of foreshortening and size change. Indeed, Gibson summarizes, we “possess a subjective scale of sizes from very large to very small.”12 Scale, by contrast, is absolute. We learn through convention that scale is a fixed relationship between two objects (such as a car and a skyscraper), but because scale remains implicit in everyday perception, it becomes unacknowledged.13 Oldenburg’s rupture of the absolute value of scale returns it to a subjective state and reveals the habitualization of ordinary vision in the process.

Phrased more explicitly in Gestalt psychological terms, these sculptural monuments thrive on the incongruent juxtaposition of non-normative figure–ground relationships. Thus, a large-scale spoon with a big cherry set in a park landscape in front of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, for example, enacts a dual act of defamiliarizing location as it is both out of place and out of scale. Developed in a series of visionary drawings in 1965, the “Proposed Colossal Monuments” were first realized outdoors in 1969 with the steel Lipstick (Ascending) in Caterpillar Tracks in New Haven. The first act of dislocation pertains to the iconography and is humorous: representations of an oversized ice cream bar, a spoon, lipstick, or a plug are removed from ordinary usage in a domestic setting and placed into a realm of absurd irreality.

| Figure 3 |

|

Claes Oldenburg, Proposed Colossal Monument for Park Avenue, N.Y.C-Good Humor Bar, 1965 Crayon and watercolor

Photo courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Copyright 1965 Claes Oldenburg |

The second act of defamiliarization, pertaining to scale, signals a different reading of how these sizeable objects affect the viewer, opening up an alternative way of generating meaning in art. This method lies not in readily comprehensible issues of subject matter and content, but in issues of how the viewer experiences shape and scale on site and over time. Commenting on how a concept of scale violation emerges from his experience of large city spaces and incongruent architectural styles—most notably the absence of skyscrapers in Europe in the mid-1960s—Oldenburg states:

[M]onuments became a significant subject for me in the spring of 1965. After a year of travel in Europe and in the U.S., away from New York, I set up in a new studio on East 14th Street. The new studio was huge—a block long—and that scale, combined with my recollections of travelling, had given me an inclination of landscape representation… I hit on the idea of placing my favorite objects in a landscape… By rendering atmosphere and the use of perspective, I made the objects seem “colossal.”14

Here, the artist emphasizes that the work’s aggressive bodily dimension toys with issues of perspectival vision. These issues are inseparable from issues of the human body and how space is perceived as the projective mapping of the three-dimensional visual world onto the two-dimensional pictorial field. Furthermore, Oldenburg’s large-scale works derive meaning from acting as obstacles to ordinary perception. As Fuchs writes,

[T]hese monuments are not just large-scale sculptures. They behave quite differently on their site. Contemporary large-scale sculpture has a tendency to please the site, fitting into it and somehow echoing it in form and scale. But Oldenburg’s monuments disrupt the site… being disruptive and incongruent makes them dramatic and self-conscious.15

A giant, melting ice cream bar wedged into a tall city block on New York’s Park Avenue (1965) is an obstacle both literally and figuratively—it impedes the flow of everyday traffic as well as the viewer’s continual perception of the visual world as a stable system of absolute scale.

Set in the context of the museum, Oldenburg’s plug acts as an obstacle to contemplative viewing. Suspended on a single, metal string from the ceiling, the Giant Three-Way Plug looms large above the heads of viewers, with its prominent cast shadow only enhancing the drama of the experience. Empty gallery space is imbued here with a newly felt intensity as a space otherwise sterile and neutral is activated. The sculpture, as a theatrical prop of sorts, launches its body into space to make us “feel” the white cube of the modern museum (or “grey cube” in the case of the stairway at the Detroit Institute of Arts) quite in the same way phenomenology has described the role of seeing, touching, and feeling in acts of direct and immediate sensory perception unsized by the intellect in its analytical capacity. To enforce a formal experience of “direct feeling,” the plug is in a heightened condition of simplified geometry as the artist abstracts its shape to bring forth a latent geometry of form with an octagonal body, two symmetrically arranged cylindrical side plugs, and two prongs. The Giant Three-Way Plug was never intended as an exact reproduction of a plug from a hardware store.16 Signification in Oldenburg’s sculpture is a uniquely configured balancing act between the “felt” sensory perception of space, objects, and bodies furthered by a condition of abstraction and the acknowledgement of the work’s iconographic status as a plug. Alternate aesthetic traditions of looking come together here, and it is Oldenburg’s violation of conventions of place and absolute scale in two related acts of defamiliarization that allows for this unique intertwinement of otherwise opposite art historical and philosophical concepts of viewing (i.e. a phenomenology of viewing furthered by the work’s latent formalism and an iconographic interpretation of image-content and object-status.)

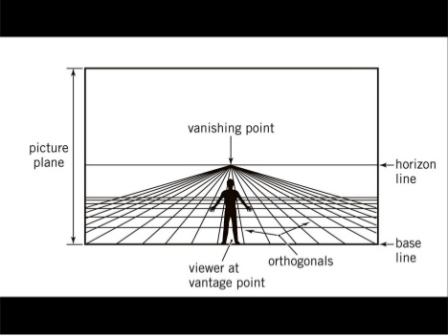

Introducing a gesture of displacement as a modern means of “composing” in 1913, Marcel Duchamp took a bicycle wheel and mounted it upside down on a stool, signed it, and declared it a variant of sculpture that he dubbed a “readymade.” Much could be (and has been) said about the two lines of historical influence—the recycling of consumer objects into high art sculpture and the employment of rules of geometric abstraction—that cross each other in Oldenburg’s practice. Oldenburg lived and worked in New York in 1962, when two new legacies of artmaking emerged side by side: Pop Art’s found object approach and the Minimalists’ abstract reliance on formal concerns with the simplicity of form, shape and space. Oldenburg’s handmade readymades play with values of Gestaltist wholeness (the geometricity of monolithic shapes perceived at once in a figure-ground union); the rejection of sculptural base in favor of placement directly on the floor, ceiling, or wall; and a conceptual relation of the work with the gallery—all of which were central to the new Minimalist art movement. Oldenburg clearly departs, however, from a straightforward phenomenology of literalist viewing toward a theatricality of vision (an aspect of his work that has been little studied) that foregrounds the mechanics of ordinary perception and insists on a unique reconfiguration of aesthetic viewing. He demonstrates a full awareness of his indebtedness to and simultaneous departure from both the Minimalist and Pop vocabulary in a 1973 collage featuring the Giant Three-Way Plug in its soft incarnation.

| Figure 4 |

|

Claes Oldenburg, Study for the Installation of Giant Soft Three-Way Plug, 1970

collage

Photo courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Copyright 1970 Claes Oldenburg |

Here, an oversized and stuffed, soft leather plug is suspended from what looks like a butcher’s hook. The sagging body hugs one of Donald Judd’s highly polished, industrially manufactured steel and acrylic Stacks—an iconic example of Minimalism customarily mounted on a wall with equal distances between the individual rectangular units, the wall, and the ceiling—implying an embrace of sorts yet to happen. In addition, the prongs can be read as an allusion to female breasts. Oldenburg’s objects do not imitate body parts (the plug is, after all, a plug), but sexual connotation occurs as a form of part-object analogy to a sexual organ.

The sexual allusion becomes more apparent in comparison and contrast to a collage by British Pop artist Richard Hamilton. In What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956), Hamilton cuts and glues magazine snippets under the artistic mantle of the Independent Group for a cover of an exhibition catalogue presented at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London. The result is an ironic commentary on the intrusion of American consumerism into British postwar society.

| Figure 5 |

|

left: Richard Hamilton, What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, 1956

collage

© This artwork may be protected by copyright. It is posted on the site in accordance with fair use principles.

right: Claes Oldenburg, Study for the Installation of Giant Soft Three-Way Plug, 1970

collage

Photo courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Copyright 1970 Claes Oldenburg |

The modern medium of collage lends itself conveniently to juxtapositions of scale as the combination of incongruent source material culled from different print magazines naturally include differentiations in size. Hamilton selects black and white imagery of a male bodybuilder and a female pin-up girl—stereotypes of hyper-sexuality circulated most prominently in the mass media of the 1950s—and places them side by side in a domestic living room. The placement humorously suggests a refashioning of the nuclear family in the image of sexual fetishes equipped with all the new gadgets of the age: a vacuum cleaner, a tape recorder, and a TV. In Oldenburg’s collage, the soft plug takes the place of the female while the hard geometric stacks by Judd play the role of the male. When viewing these two small works on paper side by side, the artistic conflation between a commodity object and human subject (and the ensuing questioning of their relation in an age of heightened postwar consumerism) and Oldenburg’s ironic displacement of the latter by the former, emerges as a key tenet of Popism. The emphasis on contrasts such as hard/soft and male/female encourages the spectator to experience the dramatic relationship between pictorial elements as sexual. In another collage, Oldenburg clips an advertisement of a Dormeyer mixer and pastes it right above and opposite the clipping of a pair of female breasts.

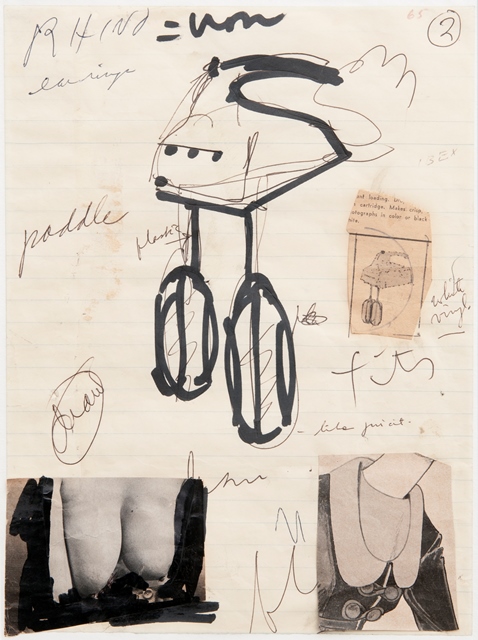

| Figure 6 |

|

Claes Oldenburg, Notebook Page: Dormeyer Mixer, 1965

Felt pen, ballpoint pen, clippings, collage

Photo courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Copyright 1965 Claes Oldenburg |

The pen drawing of the mixer links the oval shape of the two beaters to the oval shape of the breasts: all are hanging exposed, subject to the force of gravity. The clipping of the dressed female bust on the lower right hand side cleverly sets in play a tectonic analogy—the beater is the skeletal structure for the breast as skin.

Humor as a result of spatial dislocation is crucial to Oldenburg’s work. The big St. Bernard dog in the Judd-Oldenburg collage is an equivalent to the maid with a vacuum cleaner on the stairs in Hamilton’s work. Oldenburg toys with the idea of a pet soiling the white cube of the gallery space ironically as this will eventually require cleaning of sorts. The dog can be read as a Neo-Dada assault on the sterile and “sanctimonious” contemplative atmosphere of an art museum. Overall, it seems likely that Oldenburg knew Hamilton’s collage and created his in direct response to it. As the issue of projective geometry is concerned, both collages imitate a box-like space that mistakenly looks as if it follows the rules of one-point perspective. The disruptions in perspective include an upwardly flipped ground as plane (rather than a receding one), multiple viewing points jotting off into different directions (rather than meeting in a single point of virtual conflation), and oblique (rather than picture-parallel) organization of protruding objects. Depth, here, is illogical and contradictory. Principles of absolute distance and scale are violated, and so is the logical cohesion of picture content.

All of Oldenburg’s art is anti-perspectival in one-way or another. He finds distinctive ways—such as jeopardizing conventions of absolute scale—in which to undermine the place and role of the viewer as anchored and stable. In the “Proposed Colossal Monument” drawings, Oldenburg combines two incongruent viewing points (of the object and its surrounding) in an anti-perspectival manner to suspend easy identification of the object’s condition and place in art and life. Two otherwise alternative models of viewing merge in a unique theatricality of vision that insists on the simultaneous presence of opposing models of seeing. These models keep the experience of the plug alive in the eyes of the viewer and situate it in a time continuum as both phenomenological feeling and awareness of object-status. The Giant Three-Way Plug can be experienced formally when the abstract entity of shape, matter, volume, and spatial relations is “felt” phenomenologically in the act of direct experience while identification of the object vacillates between recognition of it as a representation of a plug and as a plug itself. Oldenburg creates a wedge between these two conditions, delaying the inevitable categorization and classification of the object’s conceptual status in favor of expanding the phenomenology of experience.

Art historians have linked the rejection of perspectival principles to early modern avant-garde attempts by Cubists, Dadaists, and Surrealists to jolt us out of normative perceptions of everydayness into states of awareness. In the process, they enhance the way we see the real creatively. As a particular example, the defiance of normative vision as it was practiced in Cubist painting and collage through a pictorial conflation of multiple viewing points of a single object resonates with Oldenburg’s conceptual approach to free the plug from a situation of stable viewing. To unite two objects into an incongruent relationship of scale is quite like (but not identical to) how the Surrealists relied on incongruent, nonsensical, collage-like combinations of objects to point to an underlying real more emotionally intense and authentic than what was apparent on the surface. Unlike in Surrealist thought, however, the illogical here is not a defiance of reason to bring forth the repressed order of the unconscious into the domain of the real, but a rejection of the causality and functionality of how we “see” life in ordinary vision. At no point in Oldenburg’s sculptures does visual stimulation congeal into a stable representation, keeping the experience of viewing dramatic and alive. In an ever fluctuating act of “seeing as”(as either “felt” form or representation of picture content alternate but never come together), Oldenburg locates meaning in the ambiguity and flux of a more “intense” and alive viewing.

Oldenburg’s approach to form as procedural seeks to bring back perception as a stepping-stone onto the creative as a property of the human imagination. In Edmund Husserl’s conception of the imagination as a property of daily vision, it is no longer considered the storage facility of images of the world that well up from the realm of the unconscious, but, in phenomenological fashion, the imagination is refashioned as a generator of acts of awareness with the intention to make images. The creator of imaginative images distinguishes between percept and image but is aware that both are inextricably bound together in the act of vision. The image, in this view, is neither a thing wholly internal to the mind and fantastical nor a thing external to consciousness. “Phenomenology redefines the image as a relation—an act of consciousness directed to an object beyond consciousness,” Richard Kearney notes in his discussion of Husserl’s poetics of imagining.17 The phenomenological imagination operates by means of image variation with the potential to discover in the process the underlying archetypal structure of the real by attending to the formal dynamics of objects in perception. Imaginative images, in this revisionist approach to Freudian psychoanalysis, cannot solely be mistaken for concretions of unconscious pulsional drives that well up into consciousness beyond human control from the surreality of dreams.18 In Oldenburg, the artistic imagination affects a creative re-linking of essentialized forms that combines objects with new, non-normative backdrops, as well as connects otherwise unrelated objects in diagrammatic chains of visual resemblance. All of Oldenburg’s object sculpture is linked by formal analogies intuited by the artist in acts of imaginative and conscious awareness.

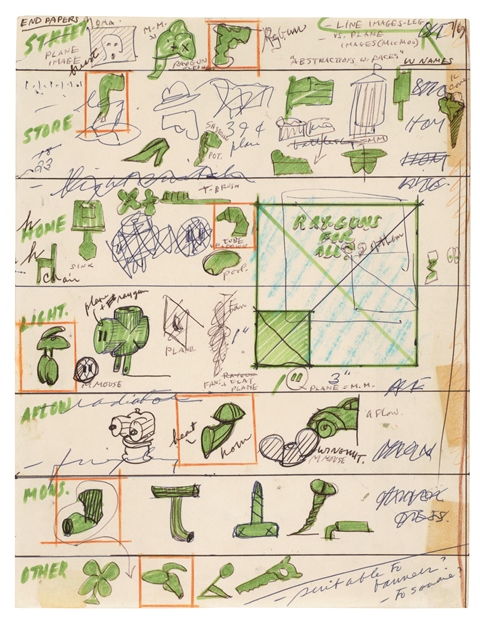

Projective Vision as Metamorphic

As a chart from 1965 indicates, Oldenburg develops the form of the plug in close connection with other commodity objects such as a fan, lamp or fire hydrant. As Husserl notes, the imagination operates “by suspending a thing’s actual or empirical existence and allowing it to float freely as an imaginary irreality amidst an infinitely open series of possibilities.”19 Variation is grounded in acts of graphic reduction to formal essences.

| Figure 7 |

|

Claes Oldenburg, Notebook Page: “Ray Guns for All?”, 1969

Ballpoint pen, felt pen, colored pencil, crayon

Photo courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Copyright 1969 Claes Oldenburg |

In the drawing’s fourth rubric from the top, titled “LIGHT,” the plug neighbors the Dormeyer mixer as the two beaters and the two prongs exert a formal “rhyming” of shape. This diagrammatic system of visual resemblance is arrived at by a reduction of a three-dimensional object to a flattened and simplified two-dimensional form. In reference to the plug, Oldenburg notes, “[it] is as if the object is going through a series of ‘impersonations’: now a balloon, now a nut, now an anchor, now a cannon—but always retaining its basic shape and identity as a Three-Way Plug.”20 Objects, otherwise unrelated, begin to relate through chains of formal connectivity. Two basic archetypes underlie all forms: a right angle symbolizes male and two parallel lines indicate female.21 (The plug and the Dormeyer mixer denote the female in the artist’s lexicon.) Formal rhyming and imaginative projection drive a vision of the real that connects everyday objects through a system of abstract reductionism in the form of two-dimensional graphic ciphers. If, as mentioned before, the key concern in projective vision is the translation of two-dimensionality into three-dimensionality, then there must be an equivalent of this strategy in the third dimension—the realm of matter.

The first version of the Three-Way Plug was executed in cardboard in 1965 and was 25 inches tall and hung from the ceiling. It was rebuilt at the Lippincott factory in steel at nearly ten feet tall for the garden of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Two additional versions were placed in the grounds of the St. Louis Art Museum and at Oberlin College in Ohio. (The plug is the second large-scale monument after Lipstick (Ascending) in Caterpillar Tracks, 1969.) Then, two approximately 11-foot tall, indoor wooden plugs (in mahogany at the Detroit Institute of Arts and in cherry at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), were followed by two “soft” Vinyl and leather/canvas sculptures.22

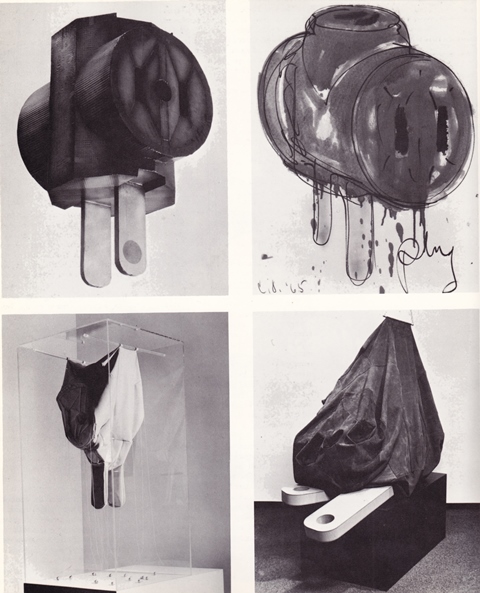

| Figure 8: a-d |

|

Claes Oldenburg, clockwise from top left: Three-Way Plug – Hard Model, 1965, cardboard; Sketch of Three-Way Plug (1965), 1972, offset lithograph; Model for a Giant Balloon in the Form of a Three-Way Plug, 1970, Vinyl; Three-Way Plug, Scale B, Soft, 1970, leather, canvas

Photo courtesy of the Oldenburg van Bruggen Studio

Copyright Claes Oldenburg |

Unlike Minimalist permutations motivated by mathematical or simple number relations, the specific behavior of different materials in conditions of hanging, sitting or standing affects variation in Oldenburg’s series. Permutation, as an experimental form-finding method with strict guiding principles set by the artist, derives from such pioneers of early abstraction as Piet Mondrian. By abstracting nature into a system of form with set dualistic relations between individual shapes, meaning is expressed through relationships of continuation and opposition. Just like in language, form and shape are tied together by a visual grammar in which meaning is established only in relationship to other forms and shapes in a syntactical framework. Oldenburg’s contribution to this history is a newly found reliance on material behavior open to chance and physical force as processes of nature beyond human control and mastery of the real through ocular disembodied vision. The materialist attitude toward variation clearly undermines the graphic essentialism as the soft plug, for example, loses its clear shape and graphic body in acts of inflation and stuffing, imbuing the work with an intensified “physical” dimension through grotesque deflation and sculptural exaggeration.

While Oldenburg’s relationship with abstraction and formal reduction is a crucial component of his work, it should not be overstated here as it has to be seen in an activated relationship with its opposite legacy of realism. In the words of the artist, “I’m not an abstract artist. I’m a realist. The way I look at it, abstraction is not sufficiently complicated: abstraction doesn’t relate enough to everyday life. You see, that is my realist bias.”23 In the end, the plug complicates a normative notion of abstraction as formalist and far removed from the material reality of the world just as much as it complicates a conception of realism as a form of transparent naturalism to be experienced in acts of ordinary vision. Oldenburg brings forth an innovative conception of realism as procedural, hallucinatory, and experience-based where the artwork acts as an obstacle to our accustomed experience. Ultimately, it is because we cannot readily feel, understand, and classify our physically intensified visual experience of the plug in prescribed ways that we linger, ponder, feel, and think more in the process.

At the heart of Oldenburg’s politics of experience lies a deeply humanistic belief in both the value of human life, and in the emancipatory capacities of a creative imagination that operates alternatively in the realm of the visual (the two-dimensional) and the material (the three-dimensional). He seeks to overcome conditions of distance—states of mediation and alienation—by bringing back into play the opposite—human contact, proximity, and physicality—and reinstating what was believed to be a tilted balance. He does so not by prioritizing one over the other (the ocular versus the body, or seeing versus feeling), but by bringing both into the drama of viewing with equal measure, and suspending their resolution. It is here that the ameliorative potential of art can set in; the viewer—at least temporarily—is taught how to look at reality differently, with the eyes of an artist.

footnotes

1 Claes Oldenburg, in “John Jones Interview with Artists,” unpublished manuscript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C., p. 9.

2 Rudi H. Fuchs, in Claes Oldenburg: Large Scale Projects, 1977 to 1980, ed. Coosje van Bruggen and Claes Oldenburg (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1980): p. 97. For alternative discussions of the plug, see Linda Downs, “Oldenburg’s Profile Airflow and Giant Three-Way Plug,” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 50, no. 4 (1971), pp. 69-78, and Ellen H. Johnson, “Oldenburg’s Giant 3-Way Plug,” Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin, XXVIII, 3 (Spring 1971): pp. 223-233.

3 Julian Rose, “Objects in the Cluttered Field: Claes Oldenburg’s Proposed Monuments,” October 140 (Spring 2012), p. 128.

4 Gibson, p. 26.

5 See Martin Jay, Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1994), p. 4. Gibson, Jay asserts, is part of an intellectual history of what he calls “ocularcentric” writers that wrongly separate sight as a privileged faculty of vision from other faculties of experience such as touching, feeling and hearing.

6 See fn1.

7 See fn1.

8 Josef Albers and others proposed this idea at the Bauhaus in Vorlehre courses. Oldenburg took courses at the Chicago Bauhaus in 1951. For an excellent discussion of Albers’s ideas on vision and art as a renewal of everyday seeing, see Eva Diaz’s chapter “Josef Albers and the Ethics of Perception,” in her recent book The Experimenters: Chance and Design at Black Mountain College (Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), pp. 15–52.

9 Claes Oldenburg, “Notes, New York, 1968,” in Claes Oldenburg: An Anthology, ed. Germano Celant (New York and Washington, DC: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, National Gallery of Art, 1995), p. 12.

10 Oldenburg, in Haskell, p. 115.

11 Oldenburg’s over twenty experimental mixed-media events (with found records, secondhand costumes, fabric props, junk-littered décor) were executed in alternative arts spaces in New York’s Lower East Side with non-professional actors who executed a series of everyday tasks, frequently incorporating random, spontaneous, and absurd behaviors that made each performance unique. They are considered part of a new genre of artmaking, the so-called “Happening” or “painter’s theater.” See Nadja Rottner, Ph.D dissertation “A Theater of Vision: Claes Oldenburg and the Emergence of the Happening,” Columbia University, New York, 2009. The author is currently at work on a manuscript entitled Theater of Vision: Claes Oldenburg and the Performing Arts.

12 James J. Gibson, The Perception of the Visual World (Cambridge, Mass.: The Riverside Press, 1950), p. 180.

13 Gibson, p. 181.

14 Paul Carroll, “The Poetry of Scale: Interview with Claes Oldenburg,” in Claes Oldenburg: Proposals for Monuments and Buildings, 1965-1969 (Chicago: Big Table Publishing Company, 1969), p. 11.

15 Fuchs, p. 97.

16 Claes Oldenburg, in Barbara Haskell, Object into Monument (Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie Press, 1971), p. 115.

17 Richard Kearney, Poetics of Imagining: From Husserl to Lyotard (London: Harper Collins, 1991), p. 15.

18 Kearney, p. 16.

19 Kearney, p. 24.

20 Oldenburg, in Haskell, p. 115.

21 Yves-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (New York: Zone Books, 1997), p. 172.

22 Oldenburg, in Haskell, p. 115.

23 Oldenburg: Six Themes (Minneapolis, MIN.: Walker Art Center, 1975), p. 9. |